The Architect of Infinity: Kazimir Malevich and the Supremacy of the Sublime

A New Genesis: The Zero of Form and the Liberation of Pure Feeling

In the early decades of the 20th century, a time of explosive political and social upheaval, the artist Kazimir Malevich emerged as a radical visionary, a figure who did not merely seek to innovate but to forge an entirely new reality. He was not a painter who simply worked within the confines of a canvas, but a philosopher who conceived of art as a spiritual and cosmic undertaking. His monumental project, which he termed Suprematism—a name signifying "the supremacy of pure feeling" in the visual arts—was a deliberate and precipitous plunge into abstraction. It was an elegant and audacious rejection of the world as it was conventionally perceived, a casting aside of the "dead weight of the real world" and the "ballast of objectivity" in a quest for a higher, purer, and more profound truth.

Malevich’s journey to this aesthetic pinnacle was a direct product of his visionary intellect. His early career, influenced by a variety of styles from Impressionism to Symbolism and Fauvism, laid a foundation for his eventual breakthrough into pure geometric abstraction. He absorbed the lessons of Cubism and Futurism, learning to geometrically deconstruct figures and suggest movement, before he took the final, revolutionary step. Unlike his contemporary, Wassily Kandinsky, who arrived at abstraction through a patient, "long path" of gradually obscuring natural forms, Malevich approached his work as a conceptual revolutionary. He did not dismantle the object, but rather, from the depths of his "creative brain," conceived of new symbolic "signs" that had no representational origin whatsoever. This ideological conviction was meticulously documented in his seminal manifestos, From Cubism to Suprematism (1915) and The Non-Objective World: The Manifesto of Suprematism (1926), which laid the intellectual groundwork for a movement that demanded a complete departure from figurative art. For Malevich, art was to find its ultimate purpose not in the imitation of nature, but in the expression of a sublime, supra-sensible realm, an experience akin to entering a new, weightless universe. His was a quest for "the zero of form," a point of pure origin from which a new artistic language could emerge, one that would "destroy the ring of the horizon and escape from the circle of objects, moving from the horizon-ring to the circle of spirit". The roots of this radical vision can be traced to his set design for the 1913 Futurist opera Victory over the Sun, where a simple black square served as the stage curtain, symbolizing the invasion of darkness and the victory over the sun itself. This pivotal moment sparked Malevich's invention of a new language of shapes and colors.

Kazimir Malevich, Set design for the opera Victory over the Sun by M. Matyushin and A. Kruchenykh, 1st Futurist Theater, St. Petersburg, 1913, 2nd Doing [Act], 5th Scene, Graphite on paper, St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music, Photo © The St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

The Esoteric Canvas: Philosophy as a Foundation for Form

To truly appreciate the ethereal quality of Malevich’s compositions—the four-dimensional geometries floating in the white infinities—one must first understand the esoteric philosophical currents that fed his creative spirit. Malevich was deeply influenced by what was known as "hyperspace philosophy," particularly the mystical writings of Russian thinker Peter D. Ouspensky and his English predecessor, Charles Howard Hinton. Unlike the scientific theories of his era, which proposed time as the fourth dimension, Malevich’s understanding of a higher reality was rooted in a spiritual, anti-materialist worldview.

Ouspensky's work, especially Tertium Organum, posited that our three-dimensional perception of the world is a mere illusion, a limited vision of a truer, four-dimensional reality that could only be accessed through a "higher consciousness" or an "intuitive capability". This vision provided Malevich with a profound theoretical framework for his art, a means to transcend the "rubbish-heap of illusion" and enter a divine realm of non-objectivity. Malevich went so far as to develop a form of "negative theology" and "mystical Suprematism," where the concept of "nothingness" was equated with the "resting God" and the "infinity of the Absolute".. He believed that the divine was incomprehensible and transcendent, and thus could only be expressed through the negation of all objective forms. His art became a conduit for comprehending the "ineffability of the Absolute," and his forms, such as the famous Black Square, were seen as mystical "signs of the absolute in total emptiness". This was a profoundly spiritual undertaking, an artistic "Unio mystica" or direct union with the divine, where all forms are reduced to "zero" in order to express the transcendent and unknowable. He also endowed his geometric forms with sacred and symbolic meaning, using the cube or rectangle to symbolize the earth and the circle to represent the sky, while even incorporating the four-pointed Orthodox cross and the red oval of the Christian mandorla in his work. In this context, his art was not merely a painting, but a philosophical text that created new meanings and accumulated metaphysical energy. He sought to use the new language of Suprematism to express apophatic infinity and render the unknowable universe through minimalism.

This is the famous painting Black Suprematist Square by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, an oil on linen canvas created in 1915. It is considered a seminal work of modern art and a foundational piece of the Suprematism movement, which Malevich founded. Suprematism sought to express "pure feeling" through the supremacy of pure geometric form, rather than depicting objects from the visible world.

The painting features a nearly perfect black square, which is not truly a square as its sides are not perfectly parallel, painted over a white background. This work was a radical departure from traditional art, representing a "zero point" in painting—a beginning and an end. It was first exhibited at the "Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10" in 1915, where Malevich hung it in the corner of the room, a position traditionally reserved for religious icons in Russian homes, suggesting a new kind of spiritual art.

The painting's surface has aged considerably, with cracks revealing the colors of an earlier, more complex composition painted underneath. Measuring 79.5 x 79.5 cm, this version of the work is housed at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

The Aesthetics of Weightlessness: An Orchestration of Space and Sensation

The visual poetry of Suprematism lies in its seemingly effortless defiance of gravity, its feeling of forms "floating weightlessly" within a boundless void. This aesthetic is a masterclass in philosophical expression, achieved through a sophisticated orchestration of color, composition, and texture. The most iconic element is the white background, which Malevich did not see as an absence of color, but as a symbolic "white free abyss" and a direct representation of "infinite space". He believed that white was the very color of infinity and the signifier of a utopian, spiritual world that could be reached only through abstraction. Within this boundless cosmos, he placed his signature geometric forms—squares, rectangles, and circles—imbued with a feeling of dynamic motion and anti-gravity. These forms are not rigidly static but are often skewed and off-center, giving them a "breathing quality" and the "illusion of movement". The composition, which eschews conventional perspective, allows the shapes to "float and move in space" in "spatially intuitive relationships," creating a sense of a "space without limits" rather than one with definite borders.

This was a direct extension of his fascination with the sensation of transcendence and flight, an interest sparked by the advent of aviation and the new perspectives offered by aerial photography. Malevich's development of Suprematism was so systematic that he divided it into three phases: color, black, and white. A closer look at the surfaces of Malevich’s works reveals an even deeper layer of luxury and feeling. Far from being cold or mechanical, his forms were deliberately hand-drawn, with "slightly uneven" lines and "chaotic brushstrokes" that leave the "expressive traces of the artist's hand" visible to the discerning eye. This tactile quality, a subtle variation in the hues of white and black, adds a humanizing warmth to the austerity of his geometry. It is a paradox: a quest for a non-objective, pure ideal achieved through imperfect, deeply personal, and human-made means. This union of the cosmic and the human is the very essence of Suprematism, a testament to its profound emotional and intellectual depth.

Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying is a 1915 oil on canvas painting by Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich. This work is a defining example of the Suprematist movement, which Malevich founded. Suprematism rejected representational art in favor of pure geometric forms, such as squares and rectangles, to express "pure feeling" rather than objective reality.

The painting features a dynamic arrangement of thirteen geometric shapes—primarily black, yellow, red, and blue rectangles and lines—set against a textured white background. The composition is not a literal depiction of an airplane, but rather an abstract representation intended to evoke the sensation of mechanical flight and the energy of modern technology.

It measures 58.1 × 48.3 cm and is part of the collection at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. The painting was originally exhibited at the landmark "Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10" in St. Petersburg in 1915, where Malevich first introduced Suprematism to the public.

Suprematism Embodied: From Canvas to the Cosmos

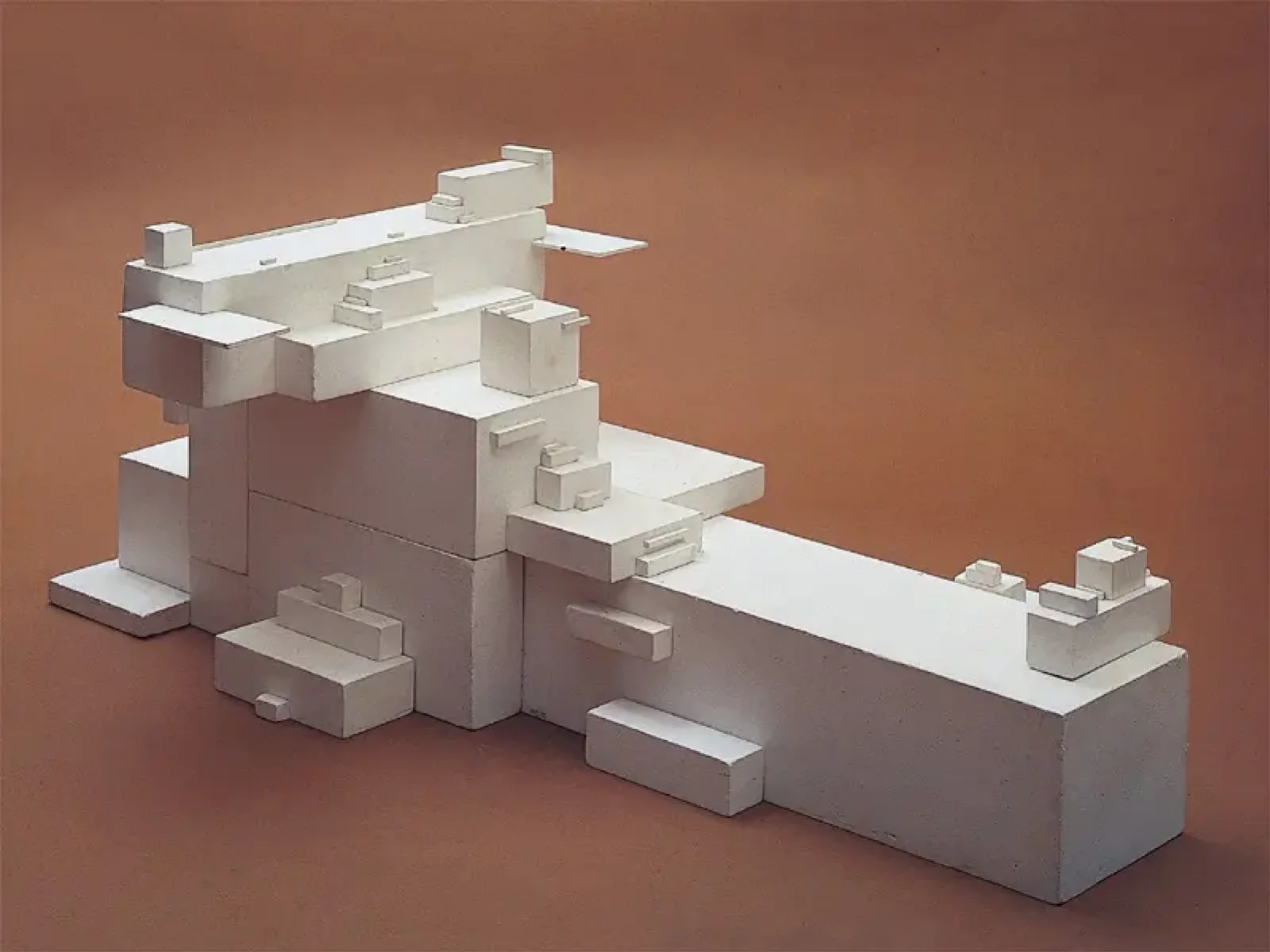

Malevich’s vision was too vast to be contained by a two-dimensional canvas. He believed that Suprematism should evolve into a "universal system of art" that would transform all aspects of life. This ambition led him to the exploration of three-dimensional forms, which he called “architectonics”, a series of white plaster models that resembled abstract skyscrapers. These works were a physical manifestation of his core philosophy, designed to demonstrate the "timeless laws of architecture" that existed independently of function and utility. The architectons were purely experimental studies of form, with no internal organization or purpose other than to explore the spatialization of abstraction and formal non-objectivity.

This pursuit of "uselessness" was a direct and powerful counterpoint to the ideology of his contemporaries in the Constructivist movement. While Malevich’s forms were meant to float freely in the exploration of a higher reality, the Constructivists were concerned with adapting art to the "principles of functional organization" and the utilitarian demands of a new society. The ideological schism underscored the deeply anti-materialist and anti-utilitarian nature of Suprematism. The architectons, therefore, were not merely sculptures; they were a profound statement of intellectual autonomy, a rejection of the mundane and a physical embodiment of a spiritual quest.

This is a gypsum sculpture by Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich from 1920, titled Architecton Zeta. This work, part of his "Architectons" series, is a prime example of Suprematist sculpture, an architectural model of a futuristic, non-functional building. The stark white, geometrically abstract forms are arranged on a horizontal axis, creating a dynamic composition of stacked and intersecting rectangular planes. The sculpture measures 31.5 × 80.5 cm and is located in the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg.

A Legacy of Paradox: From Revolution to Subversion

The meteoric rise of Suprematism mirrored the turbulence of the Russian Revolution of 1917, a time when the avant-garde was seen as a creative mirror to the radical social change that was sweeping away the old imperial order. Initially, Malevich was a favored figure, holding prominent teaching positions, but this period of synergy was tragically brief. The iron fist of Stalinism brought with it a suffocating cultural policy known as Socialist Realism, which mandated that art must serve as a tool for state propaganda, condemning abstraction as "unintelligible" and "idealistic philosophy". Artists who did not comply faced dire consequences, including censorship, imprisonment, and even death. In 1930, Malevich himself was imprisoned for two months, and his artworks and manuscripts were confiscated.

In response to this brutal repression, Malevich was forced to abandon his pure abstraction and return to figurative painting in the years before his death in 1935. Yet, this return was no simple capitulation. With a poignant and profound sense of subversion, he applied the visual language of Suprematism to his new figurative subjects—especially portraits of peasants and workers—transforming them into powerful critiques of the regime. The once spiritually infinite white space of his canvases took on a new, more somber meaning, suggesting a "void" or "oblivion" that had consumed the Soviet dream. His figures were stripped of their individuality, their featureless faces and rigid postures rendering them "lifeless figurines" or "puppets". By taking the glorifying tropes of Socialist Realism to their logical extreme, Malevich exposed the "inherent absurdity and consequent oppressiveness of the Stalinist agenda". This final, defiant phase of his career proved that Malevich's non-objective principles were not a rigid style but an enduring intellectual language, a tool that could express both the heights of spiritual freedom and the depths of human despair.

This is the oil on canvas painting Head of a Peasant Girl by Kazimir Malevich, created in 1913. A key example of his Cubo-Futurist period, the work deconstructs the subject into a complex arrangement of dynamic, intersecting planes and geometric shapes. The warm, earthy tones of green, yellow, and brown dominate the composition, while sharp angles and fragmented forms create a sense of movement and energy, typical of the Futurist style. Measuring 72 × 74.5 cm, the painting is currently held in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. It was previously exhibited at the "Kazimir Malevich. His Path from Impressionism to Suprematism" exhibition in Moscow in 1920.

Conclusion: The Enduring Pursuit of the Sublime

The legacy of Kazimir Malevich is one of an artist who was a true pioneer of the sublime. His concepts of "four-dimensional geometries floating in the white infinities" were not just stylistic choices but a direct and eloquent expression of a holistic worldview that sought to liberate the human spirit from the constraints of a limited reality. From the iconoclastic Black Square that marked the "zero point of form" to the ethereal Suprematist Composition: White on White that embodied infinity itself, his works remain a radical challenge to our perception of art and existence.

Suprematism’s influence, transmitted through his followers like El Lissitzky, extended into the Bauhaus and beyond, shaping the course of modern design and minimalist art for generations. Though his art was suppressed by an unyielding state, the philosophical and aesthetic principles he laid down endure. Malevich's final, poignant works revealed that his was a language of pure feeling that could not be silenced, a testament to the enduring power of a singular vision to transcend the limits of both the canvas and the corporeal world.