The Forging of a Legend: Goro's, A Philosophy Embodied in Silver and Gold

Goro’s the brand with an 8 hour queue everyday

Tokyo is a city of elegant contradictions, a place where neon futurism collides with the silent rituals of centuries past. To walk the streets of Jingumae, just beyond the grand torii gates of the Meiji Shrine, is to be surrounded by a kaleidoscope of manufactured desires. The avenues here are home to fashion’s great empires: Louis Vuitton in its glass fortress, Dior in its modernist temple, Comme des Garçons in its conceptual defiance. Step into one of these flagships, and you are immersed in theater. The walls gleam with polished glass, monograms multiply like sacred glyphs, and trained associates speak in hushed voices as if presiding over a sacred mass. At Cartier, spotlights gleam across vitrines like altars, each jewel placed as though it were a relic. The architecture is designed to overwhelm, to persuade the customer that they have crossed a threshold into transcendence.

Here, luxury is a spectacle, its value measured not only by scarcity but by how loudly it can announce itself. On weekends, shoppers queue outside Nike’s flagship for the latest limited release, while teenagers in Harajuku frill and clash in kaleidoscopic layers of identity. Yet, behind the curtains of this theater lies a global machine. The same handbag or bracelet is replicated in factories, transported in climate-controlled boxes, and delivered simultaneously to boutiques in Tokyo, Paris, and New York. Scarcity is not natural but orchestrated—an illusion to amplify desire.

And yet, tucked unassumingly on a quiet side street, there is a storefront that refuses spectacle altogether. The façade is plain, the signage modest, the window nearly empty. The uninitiated might pass by without a second glance. But for those who know, this door is the threshold to a different reality. This is Goro's. Here, there is no theater, no spectacle, no amplification. The value is not manufactured—it accumulates naturally, through ritual and time. To step inside is to encounter the opposite of luxury’s spectacle: a world where meaning is whispered, not shouted. In a world where “luxury” has become synonymous with mass production masquerading as exclusivity, Goro's presents a startling alternative. Here, value is not engineered through scarcity campaigns but is forged through an ethos of authenticity so uncompromising that it feels almost alien in the twenty-first century. This is the future of luxury, an ethos of authenticity so uncompromising that it feels almost alien in the twenty-first century.

The name belongs not only to the shop but to the man who founded it: Goro Takahashi, a silversmith, leatherworker, pilgrim, and seeker. To step into Goro's world is to enter a realm where the rules of consumerism dissolve. There is no marketing, no seasonal collections, no international boutiques designed for rapid expansion. Instead, there is ritual, mystery, and an unbroken chain of philosophy that has survived its founder’s death. In a world where “luxury” has become synonymous with mass production masquerading as exclusivity, Goro's presents a startling alternative. Here, value is not engineered through scarcity campaigns but is forged through an ethos of authenticity so uncompromising that it feels almost alien in the twenty-first century.

The Origins of a Master: From Tokyo to the American West

The legend of Harajuku’s Goro Takahashi

A Beginning Made by Hand

In postwar Tokyo, before Harajuku acquired its grammar of neon and spectacle, a boy learned to listen to materials. Hide, sinew, thread: each had a sound, a resistance. On a small worktable that smelled of oil and cut leather, Goro Takahashi first discovered that making is a conversation—one conducted in pressure and patience rather than words. The story, often told in half-whispers, begins with a brief but decisive apprenticeship: an American soldier, passing through Japan in the uneasy quiet after the war, showed the boy how to cut a strap straight, how to set a rivet clean, how to burnish an edge until it glowed like dark honey. It was not a formal program but a simple transmission of knowledge—a hand guiding a hand. This was the first grammar of Goro’s life: a profound respect for the humble tool and the understanding that an object reveals its truth only to those who refuse to hurry.

Shokunin: The Discipline Beneath the Gesture

Japan has a word for this craftsman’s spirit: shokunin kishitsu. It is not a style, nor merely a skill, but a moral posture—a vow to approach one’s work with a spiritual duty to achieve excellence. This posture shaped Goro more than any single technique. He left formal studies not out of rebellion, but out of fidelity to a different curriculum: repetition, exactness, and silence. Repetition became prayer; exactness, devotion; silence, the condition under which objects speak. In the cramped workshops of a Tokyo still finding its feet, he learned to finish what no one would see: inside seams, the underside of a buckle, the hidden stitch that carries the load. It is in these unseen spaces that a maker declares his ethics. Long before he forged silver, Goro decided that nothing he made would speak falsely.

The Cultural Epicenter of Harajuku

Harajuku’s later myths—Lolita layers, avant-garde storefronts—obscure its earlier intimacy. In those days, the neighborhood was more air than architecture, more idea than address. Rockers and bikers moved through it like a weather system, importing fragments of Americana and remaking them in a Japanese key. Goro stood inside that current but did not let it carry him away. He made belts that held, wallets that refused gimmick, small objects that earned their patina honestly. As Harajuku evolved into the epicenter of youth culture, his small shop became a sanctuary and a point of convergence. It was here that the pioneers of the Ura-Harajuku movement, the tastemakers who would define Japanese streetwear for a generation, came not just as customers but as disciples. Figures like the legendary Hiroshi Fujiwara were early devotees, recognizing in Goro's work an authenticity that stood in stark contrast to the fleeting trends of the world outside his door. Their quiet co-sign, passed through whispers and seen in street-style photographs, helped elevate Goro's from a local secret to a global legend.

The West as a Horizon

Before he saw the deserts of Arizona with his own eyes, Goro knew them through images: a sky that refused to end, mesas like altar steps, metal worked by hands that learned from wind and stone. The American West arrived in Tokyo as a rumor of freedom—unfenced distances, work whose function was its beauty. For a young maker trained in Japanese restraint, the rumor made a promise: there exists a place where utility and myth are the same word.

He journeyed there, first in fits and starts, then with the intentionality of a pilgrimage. He sought lessons that could not be bought with tuition but were traded for respect, for humility, for leather goods that could be used hard. He learned the feel of an ingot hammered thin against a well-worn anvil; the gritty softness of tufa stone molds and how they record a gesture in negative; the logic of chisel and file, where subtraction is more expressive than addition. The men who showed him did not lecture. They made—and in the making, they said what mattered: do not rush the temper; do not lie with the finish; do not be clever where honesty will do.

The Desert's Instruction

Out there, the land is a text you read with your skin. The desert taught Goro proportion. The small must be true because it stands next to the infinite. A silver feather must carry the right weight because the sky is heavy with meaning. Its curvature cannot be invented; it must be observed. Real feathers are marvels of engineering, reconciling flight with gravity. If silver is to speak of "feather" honestly, it must reconcile its own weight with a sense of lift. He began to carve with a different attention: barbule lines that are not decorative but structural; a rachis that thickens where a wing would need strength; edges finished not to glitter but to glow, like bone under skin. He was not creating a copy of a feather, but a translation of its spirit.

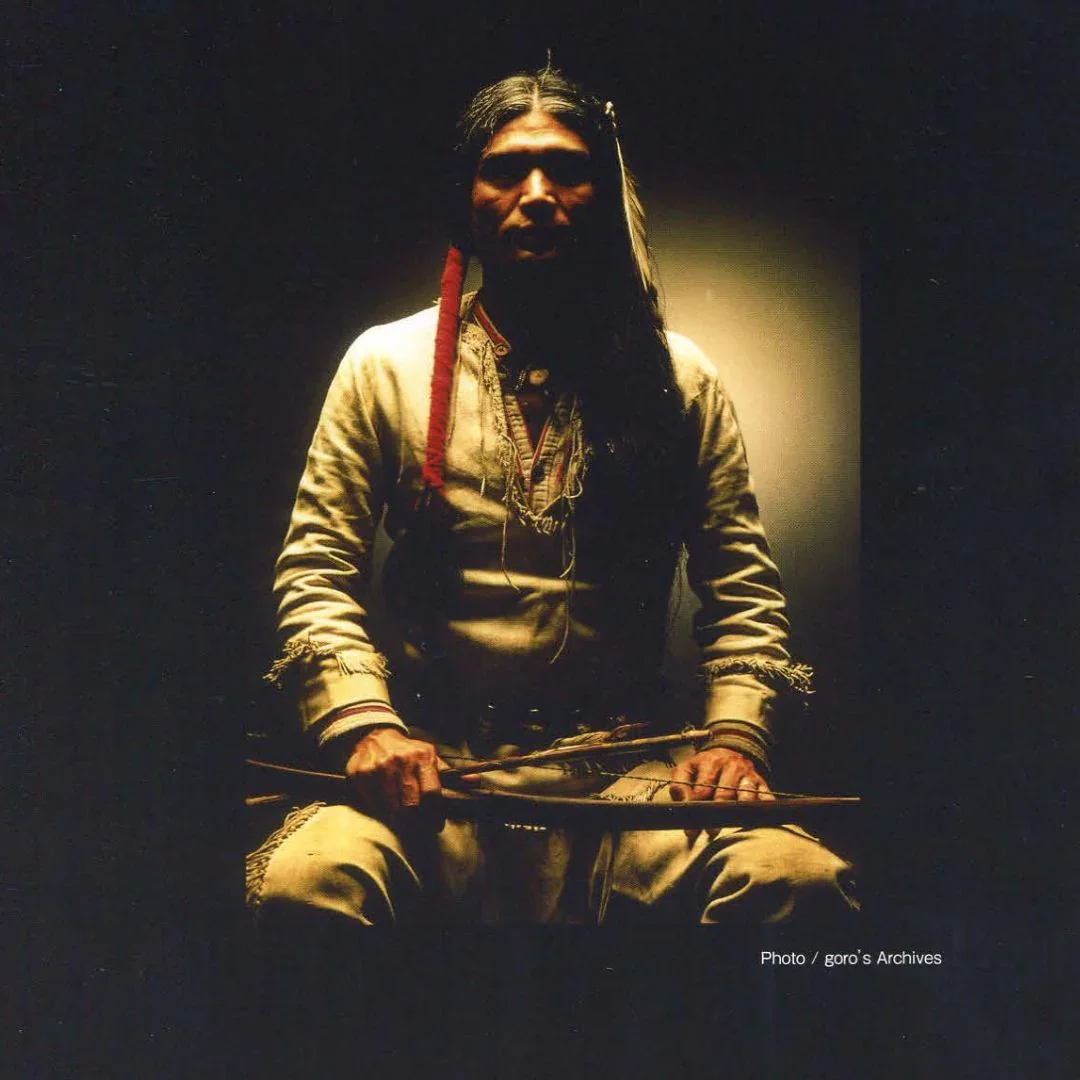

The Sacred Calling of "Yellow Eagle

Platinum head all gold eagle from Goro Takahashi

Names, in every tradition, are more than identifiers. They are vessels of spirit, shaping destiny, embodying both the weight of ancestry and the burden of responsibility. For Goro Takahashi, the man who would become known simply as Goro, there was a moment when his name was not enough—when another title, older than himself, descended upon him like a mantle of divine inheritance. That name was “Yellow Eagle.”

It was not an affectation, nor a chosen nickname. It was not the kind of moniker one selects for its resonance in commerce or style. Instead, it was a consecration. To be given the name “Yellow Eagle” by elders of the Lakota Sioux was to be folded into an unbroken chain of spiritual guardianship, one that transcended culture and geography, piercing into the eternal.

A Pilgrimage to the West

In the 1970s, when most Japanese designers were orienting themselves toward Paris or Milan, Goro turned his eyes to a very different horizon: the American West. The land of open skies, of stark mesas and endless plains, where freedom was both physical and metaphysical. Goro’s journey was not touristic; it was not about consumption or surface fascination. It was, from the outset, a pilgrimage.

When he arrived in the United States, he carried little more than a restless heart and the tools of his craft. He sought not only new techniques in silversmithing but a deeper connection to the primal sources of creation—the earth, the animal, the spirit. He found these not in the ateliers of New York but in the sacred fires of Native American ceremonies.

Among the Lakota Sioux, Goro was not treated as a foreign curiosity but as a seeker. They recognized in him the same intensity of spirit that had animated their own artisans, medicine men, and warriors for generations. And so, they welcomed him into their circle.

The Vision Quest

It was during one such immersion, amid the rites of the Lakota, that the name came to him. A vision quest, the deeply sacred practice of isolation, fasting, and communion with the divine, became the crucible of his transformation. Alone in the wilderness, Goro confronted himself, his fragility, and his calling. Days without food, exposed to the elements, left him stripped of all illusions.

And then, the eagle appeared.

Not in metaphor, but in startling clarity—a golden figure descending against the twilight sky, circling, watching, blessing. The eagle, in Native American cosmology, is the highest of messengers, the intermediary between the Creator and humanity. To dream or see the eagle is to be summoned into a higher order of life, one bound to vision, courage, and protection.

When Goro emerged from the quest, gaunt but radiant, the elders conferred upon him the name “Yellow Eagle.” It was not a symbolic courtesy—it was a recognition of transformation. He had crossed the threshold from outsider into kin, his soul recognized as part of their spiritual ecology.

The Burden of the Name

For Goro, the name was not a decoration; it was a burden. To carry the eagle meant to embody its attributes: vigilance, wisdom, and guardianship. It also meant responsibility for the sacred symbols he would later translate into silver and leather. The feathers, the thunderbirds, the animals—all of these would cease to be mere motifs and become, instead, carriers of power.

“Yellow Eagle” was a reminder that his work was not simply design. It was liturgy. Each pendant hammered from silver was less an accessory than an offering; each leather bracelet dyed and cut was less a product than a prayer. His studio in Tokyo became a kind of sweat lodge, where metal met fire and spirit poured into form.

Cultural Crossroads

This sacred naming also placed Goro at one of the most unusual cultural crossroads of the 20th century. A Japanese artisan, formed in the precision of Edo craft traditions, recognized as kin by the Lakota Sioux, and eventually idolized by fashion-conscious youth in Harajuku—few lives embody such seamless crossings of worlds. Yet for Goro, there was no contradiction.

He once said that Japan and the Native American tradition shared an understanding of animism—the belief that stones, animals, rivers, and skies are not inert but alive. In this sense, his identity as “Yellow Eagle” was not a renunciation of his Japanese heritage but its expansion into a universal register.

The Calling Made Flesh

To the young men and women who lined up for hours outside Goro’s Tokyo shop in later years, “Yellow Eagle” was perhaps a distant myth, a romanticized story attached to the man behind their coveted accessories. But to Goro himself, it was not myth. It was the defining truth of his life.

He understood that to wear a feather was not merely to decorate the body—it was to call down the protection of the skies. To wear a thunderbird was to carry a shield of lightning. To wear a piece of his silver was, in effect, to become part of the covenant he had made during that vision quest.

Thus, when he hammered metal in his workshop, he did so with the solemnity of ritual. His hands were guided not merely by technique but by vow. The eagle had seen him; the elders had named him; the Creator had marked him. His work would forever be testimony to that calling.

The Pilgrimage to Omotesandō: An Unconventional Business Model

Inside the Goro’s store on Omotesandō

In the familiar world of global luxury, the act of purchasing is a seamless, flattering choreography. Goro's, however, is defined by its refusal of this ease. To own a piece of Goro Takahashi’s world requires submission to a ritual that borders on pilgrimage. One does not simply buy Goro's; one is deemed worthy—or not.

The pilgrimage begins long before one steps foot in Tokyo. It begins in whispers, in grainy magazine features, in fleeting glimpses of feathers on the necks of cultural icons. The initiate realizes: if they wish to possess a piece, they must go to Omotesandō. There is no online shop, no worldwide distribution. One must go directly to the source.

The first trial is the threshold itself. From dawn, hopefuls line the narrow street, some arriving in the dead of night to secure a place in the day’s lottery. This system of randomized entry is the first gate of initiation. Waiting becomes part of the ritual, transforming the jewelry from mere ornament into an object of endurance. The line is not an inconvenience—it is the threshold at which desire is tested. In these hours, strangers become comrades, sharing stories of past visits and dreams of future acquisitions. This is luxury inverted: instead of the brand serving the customer, the customer must serve the legacy.

Inside, the store is modest, almost austere. The staff are not salespeople but custodians of a mythology. Browsing is not permitted. Instead, the staff assess, with an almost priestly discretion, whether a piece is right for the wearer. The jewelry must find its custodian; the custodian cannot simply demand the jewelry. This is where the power dynamic is fully inverted. In the conventional luxury market, the customer is king. At Goro's, power flows not from money but from loyalty and humility.

For many, the ritual ends in refusal. To be told “no” at Goro’s is not failure but an initiation into its deeper ethos. Denial becomes a kind of benediction, transforming ownership from a matter of wealth into a matter of fate. Those who are turned away carry with them not resentment, but an intensified longing.

When, at last, a piece is granted, the act of acquisition is closer to consecration than to a transaction. The feather, the sunburst, the thunderbird—these are tokens of a spiritual economy where scarcity is not a marketing strategy but a core principle. The paradox is that this refusal to conform to the commercial logic of expansion made Goro’s the most coveted of all. In a world of mass luxury where everything is accessible for a price, Goro’s remained a threshold one had to earn the right to cross.

The Spiritual Weight of the Feather

There are objects that exceed their physical form, and a single feather crafted by Goro Takahashi belongs to this rare class. It is not simply jewelry; it is a living metaphor, a vessel of meaning, a talisman that unites history, spirit, and personal journey.

In the tradition of the Plains tribes, from whom Goro drew profound inspiration, feathers were not ornaments but sacred texts. Each feather told a story: of valor, of visions, of prayers carried skyward. An eagle feather, especially, was revered as the mediator between earth and heaven. To wear one was not an act of decoration but a covenant, and it was this covenant that Goro sought to transmit through silver. He did not simply replicate feathers; he embodied their ritual weight.

The paradox of a Goro's feather lies in its materiality. Silver is a dense, cold medium, stubborn under the hammer, yet through his hand, it yielded a form that conveys air, flight, and breath. To hold one is to feel this contradiction: it is at once heavy and light, finite and infinite. It gleams with worldly luster, yet points to realities beyond the material. Goro believed the act of creation itself was sacred. He once remarked that he did not “make” feathers but “released” them from the silver, as though they had always been waiting inside, asking to be born.

For true initiates, the feather becomes a mirror of their life. It absorbs one’s journey, darkening with skin oils, softening with years of wear, developing a patina unique to its owner. The silver grows warm, becoming less an adornment than a second skin. Each scratch becomes a line in a biography. In this way, the object accumulates its own spiritual weight. It no longer represents only the mythic eagle; it begins to represent the wearer’s own becoming. It asks the wearer a question: Are you ready to carry this?

A Legacy Preserved

Set from Goro Takahashi

The story of Goro's does not end with the man. A legacy worthy of reverence must be preserved not in static monuments but in living practices. The preservation of Goro's is closer to that of a spiritual lineage, where elders transmit wisdom to disciples not to perpetuate ownership, but to safeguard meaning.

Today, Goro’s children and apprentices carry forward his methods with uncompromising fidelity. They do not simply produce jewelry; they enact a ritual. Yet, what survives is not just the technique but the very ethos of restraint, devotion, and pilgrimage. The business model remains intentionally unconventional. The line still forms each morning, a congregation of believers waiting not merely for objects, but for an encounter with a spirit. In this way, the legacy is preserved not in the jewelry alone but in the ritual that frames its acquisition.

The name “Yellow Eagle” did not die with Goro Takahashi; it took flight. The legend has only grown stronger, whispered in skate parks, retold in music lyrics, passed from collectors to the curious. This myth is as crucial as the jewelry itself. Without it, the silver feathers would be mere adornments; with it, they are talismans, binding the wearer to a lineage of seekers.

To preserve such a legacy means resisting the world’s demands for convenience. It means honoring the time it takes to craft, the patience it takes to wait, and the humility it takes to seek. It means remembering that true luxury lies not in abundance but in scarcity, not in possession but in pilgrimage. And it means recognizing that in every feather, in every eagle, in every worn pendant, the spirit of Yellow Eagle still soars, eternal.