Hiroshi Fujiwara and the Architecture of Post-Luxury Influence

An architecture of intention, where scarcity becomes authority and the monogram becomes philosophy.

Every era produces its architects of culture — figures whose work transcends the object and instead builds systems, codes, and structures of meaning. In the nineteenth century, luxury houses constructed dynasties whose monograms became secular sacraments of permanence. In the twentieth century, designers built empires whose names became synonymous with spectacle. But in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a new paradigm emerged: influence not as empire but as architecture, not as spectacle but as sanction. At the center of this paradigm stands Hiroshi Fujiwara. To describe him merely as a designer, DJ, or tastemaker is to diminish the structural significance of his role. Fujiwara is not an executor of trends but their architect. He is a figure who demonstrates that influence can be constructed discreetly, sustained invisibly, and expanded intentionally. His Fragment Design lightning bolt is not a logo in the conventional sense; it is a creative thumbprint, a monogram of philosophy, an imprint of intentionality. This study, Hiroshi Fujiwara and the Architecture of Post-Luxury Influence, seeks to analyze Fujiwara not as an individual designer but as a cultural architect whose work exemplifies the condition of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. We will explore how his career reframed Harajuku as a counterpoint to old-world luxury, how his philosophy dissolved the boundaries between art, design, and life, how his logo functions as a monogram of resonance, how his collaborations expanded his architecture across global industries, and how his intentionality produced a legacy capable of enduring without empire. The central argument is clear: Fujiwara has revealed a new blueprint for influence. His career proves that the most powerful cultural force of our age is not inheritance but intentionality, not spectacle but discretion, not permanence of object but permanence of meaning.

The Unseen Force of Modern Culture

Hiroshi Fujiwara is often introduced through superlatives: the “godfather of streetwear,” the “living internet,” the first true Japanese DJ of hip-hop. Each of these labels is true, yet each is insufficient. They describe events, not essence. To understand Fujiwara is to understand not what he produced, but what he architected. His real work is not a shoe, a shirt, or a collaboration—it is the system of influence within which those artifacts became resonant.

He is, above all, an architect of the unseen. Unlike designers who construct empires around their names, Fujiwara resists spectacle. He operates in deliberate obscurity, yet it is precisely this discretion that magnifies his cultural authority. His influence is measured not by his visibility but by his imprint, a mark that recurs across generations of brands, collaborations, and movements.

The paradox of Fujiwara’s career is that of discreet omnipresence: he is everywhere, and yet almost nowhere. His role is to engineer conditions under which others thrive, to sanction objects with a lightning bolt, to mentor disciples who will themselves become architects. He is less a sovereign than a code, less a monarch than a matrix.

Influence Without Empire

Traditional designers often equate influence with empire. Giorgio Armani built a global labyrinth of boutiques. Karl Lagerfeld transformed Chanel into a perpetual spectacle of logos and runways. Even Rei Kawakubo, iconoclast though she was, constructed a monumental presence through Comme des Garçons’ relentless expansion. Influence, in these models, is tethered to scale: the more visible, the more powerful.

Fujiwara inverted this equation. His company, Fragment Design, employs only a handful of people. Its output is intentionally narrow, sporadic, and elusive. Rather than expansion, Fujiwara chose contraction. Rather than visibility, he chose opacity. And yet, his cultural authority radiates across the globe. He has shaped Nike’s sneaker strategy, Louis Vuitton’s embrace of streetwear, and the global template for collaboration as a business model.

This is influence without empire. It is the architecture of smallness, where scale is not achieved through corporate growth but through philosophical dissemination. Fujiwara’s influence does not depend on owning factories, stores, or even archives. It depends on the intentionality of the stamp—the recognition that if an object bears his sanction, it enters a higher order of cultural resonance.

The Architecture of Discreet Authority

Every architect builds with constraints. Fujiwara’s chosen constraint is discretion. His Fragment Design logo, the double lightning bolt, is not emblazoned across billboards, nor is it turned into wallpaper on handbags. It appears small, almost hidden, sometimes only visible to those who know where to look. It functions not as advertisement but as affirmation: a subtle signal that the object has passed through Fujiwara’s filter of taste.

This is an architecture of discreet authority. Authority, in this model, is not broadcast; it is conferred. It is less proclamation than benediction. The consumer does not wear a lightning bolt to announce status to the world; they wear it to recognize themselves within a code. This is the inversion of the luxury logo: where the Louis Vuitton monogram screams inheritance, the Fragment bolt whispers initiation.

Discreet authority is also Fujiwara’s personal mode of operation. He appears in interviews reluctantly, avoids spectacle, and shrinks from the machinery of fashion weeks. His power is cumulative rather than performative. Each collaboration, each discreet sanction, builds upon the last, creating a long arc of consistency that defines his legacy.

The Invisible Network

To understand Fujiwara’s cultural architecture, one must trace the invisible network he constructed. His mentorship of NIGO led to A Bathing Ape, which would globalize Japanese streetwear. His support of Jun Takahashi nurtured Undercover, which became a lodestar of experimental fashion. His collaborations with Nike redefined the sneaker as a cultural artifact, not just athletic gear. His partnership with Louis Vuitton sanctioned streetwear within the highest echelon of luxury.

This is not coincidence; it is structure. Fujiwara operates as a node of connectivity, a nexus through which ideas pass, mutate, and proliferate. Like the internet, he does not dictate content but enables circulation. His genius is in creating ecosystems rather than empires, networks rather than monuments. He is not the castle but the bridge.

Here we glimpse the radical difference between Fujiwara and the traditional designer. The old model builds vertically: empire, maison, dynasty. Fujiwara builds horizontally: network, collaboration, ecosystem. Vertical power requires control; horizontal power requires connection. Fujiwara’s architecture is the latter—an invisible scaffolding that supports others while remaining understated itself.

Philosophy as Practice

Fujiwara insists he is not a designer but a “creative.” This statement, often misunderstood as modesty, is in fact precise. Design, in the conventional sense, produces objects. Creativity, as Fujiwara defines it, produces conditions. His work is conceptual functional art: conceptual because the idea—the sanction, the code, the aesthetic gesture—matters more than the physical object; functional because these ideas embed themselves into the objects of everyday life.

A Fragment sneaker is not just footwear; it is a philosophical statement about scarcity, authority, and discretion. A Fragment collaboration with Starbucks is not about coffee; it is about embedding taste into the most banal of commodities, transforming them into carriers of cultural meaning.

In this way, Fujiwara dissolves the old distinction between art and life, between philosophy and commerce. Every collaboration becomes a philosophical act, every product a structural beam in his architecture of being.

The Logic of Permanence Through Transience

Fujiwara’s influence appears paradoxical: how can someone so discreet, so resistant to permanence, sustain such lasting authority? The answer lies in his embrace of permanence through transience. Each drop, each limited edition, each fleeting collaboration is designed to vanish. Yet it is precisely this transience that creates permanence in cultural memory. Scarcity begets myth; absence begets aura.

This recalls Walter Benjamin’s notion of the aura of the artwork: its uniqueness, its unrepeatability, its distance. Old-world luxury once offered aura through craft and heritage. Fujiwara generates aura through transience, through the deliberate refusal of scale. His lightning bolt carries aura not because it is everywhere, but because it is rare, discreet, and sanctioned.

Fujiwara as Cultural Architect

To call Fujiwara a cultural architect is not metaphorical but structural. He does not build buildings, but he builds systems. He does not draft blueprints of stone, but he drafts codes of meaning. His architecture is invisible but no less load-bearing. Like the hidden beams that hold up a cathedral, his influence sustains entire industries of streetwear, luxury, and collaborative culture.

Architecture is not only about form; it is about intention. Fujiwara’s career is defined by intentionality. He chose discretion over spectacle, smallness over empire, networks over monuments. Each choice was structural, each decision reinforcing the architecture of discreet authority.

The Prototype of Post-Luxury

Fujiwara embodies the prototype of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. In this paradigm, value is not inherited but earned, not broadcast but whispered, not mass-produced but intentionally scarce. His Fragment Design monogram functions not as ornament but as imprint, not as decoration but as sanction.

He is the unseen force of modern culture: a figure who proves that true influence requires no empire, no monument, no spectacle. It requires only architecture—of ideas, of networks, of intention. Fujiwara has built such an architecture, and in doing so, he has reshaped the very conditions under which culture assigns value.

The Architecture of Cultural Authority

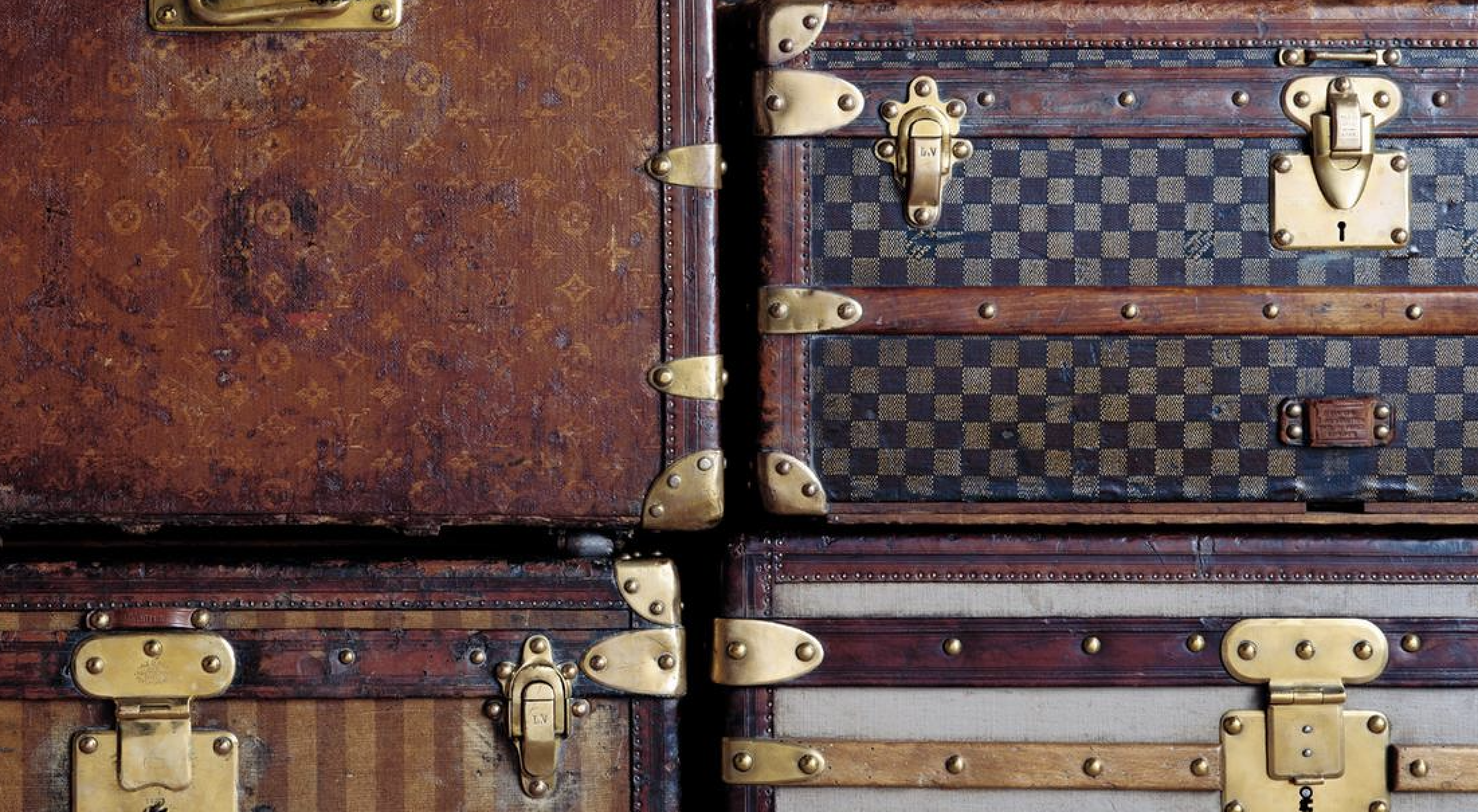

Luxury, as we have inherited it, has always been a matter of inheritance. From the salons of Paris to the ateliers of Florence, value has been defined by lineage—by maisons whose monograms were less decoration than dynastic heraldry. To wear Hermès or Louis Vuitton was not merely to own an object but to participate in a genealogy, to extend one’s self through the permanence of a house that promised to outlive its wearer.

But in the late twentieth century, this model began to fracture. Scale eroded sanctity, repetition hollowed out ritual, and the monogram became a tired echo of itself. Luxury, once anchored in intention, collapsed into reflex. What was once sacred became mere habit of consumption.

It was within this vacuum that Hiroshi Fujiwara emerged. Not as a designer in the traditional sense, but as a cultural architect, orchestrating from Tokyo’s Harajuku a new grammar of value. His imprint, Fragment Design, and the discreet thunderbolt monogram that accompanies it, operate not as a brand in the conventional sense but as a creative thumbprint—a stamp of sanction, a mark of curated authority.

Fujiwara’s work cannot be reduced to fashion; it must be understood as Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. In this paradigm, objects derive their resonance not from material worth or aristocratic lineage but from intentional scarcity, cultural connectivity, and philosophical weight. The lightning bolt is less a logo than a seal of approval; his collaborations are less products than structural beams in a wider architecture of influence.

This study argues that Hiroshi Fujiwara is not merely a participant in culture but a constructor of it: an architect who reframed the very possibility of value. His career must be read as a long-form manifesto, a deliberate act of engineering influence. To trace Fujiwara’s trajectory is to study the monogram as cultural imprint—not as ornament, but as structure; not as inheritance, but as authorship.

The Genesis of a Counterpoint: Tokyo’s Harajuku Scene

To understand Hiroshi Fujiwara’s ascendancy as a cultural architect, one must begin not with his later collaborations or global recognition, but with the urban crucible that forged his sensibility: Tokyo’s Harajuku in the 1980s and 1990s. Harajuku was not simply a geographic district; it was an architectural condition—a street-level academy where rebellion, curiosity, and cultural importation were rehearsed into a new grammar of value. If Paris in the nineteenth century was the birthplace of haute couture, then Harajuku in the late twentieth century was the site of its deliberate dismantling, a stage on which Fujiwara orchestrated a counter-philosophy to the hollow monuments of old-world luxury.

This video, "The BEST Harajuku Fashion Brand Of The 90s?!?!" by Dolcejeanz, is not a general survey of 1990s Harajuku street style. Instead, it is a deep-dive analysis of a single, highly influential brand from that era: Beauty:Beast, and its creator, Takao Yamashita.

Harajuku as Anti-Paris

In the 1980s, Japan’s economic bubble had cultivated an insatiable appetite for European luxury. The monogrammed bags of Louis Vuitton, the gilt interlocking Cs of Chanel, the rigorous codes of Hermès—all were not merely consumer goods, but tokens of participation in a global aristocracy of appearances. Luxury in its European incarnation was a code of inherited status: one bought not only the bag, but the imagined membership in a lineage of nobility, of salons, of maisons whose very architecture announced permanence.

Harajuku was the inversion of this. It was, in its original form, an illicit street laboratory. Youth gathered not around monuments of stone, but asphalt intersections, storefronts, and record shops. Harajuku was ephemeral, shifting, unstable—a built environment in which impermanence itself became the condition of creativity. Against the static weight of Parisian luxury, Harajuku asserted fluidity. Where Europe offered inheritance, Harajuku insisted on invention.

Fujiwara’s genius lay in recognizing this condition and formalizing it into a philosophy. Harajuku was not to be consumed as a passing subcultural fad; it was to be architected into a system of influence.

The Pilgrimage of a Cultural Conduit

Born in Ise, a city of shrines and tradition, Fujiwara’s flight to London and New York was not escapism, but initiation. The adolescent encounter with punk rock in London—Vivienne Westwood, Malcolm McLaren—offered him a first template for rebellion as style system. Punk was not merely clothing; it was philosophy materialized in leather, safety pins, and attitude. It announced that value could be created not by craft alone, but by ideology stitched into textile.

New York, in contrast, revealed to him hip-hop: a seamless convergence of music, dance, fashion, and visual art into a unified lifeworld. Hip-hop was not compartmentalized; it was an ecosystem of cultural production where sneakers, graffiti, and sound operated as equivalent registers of expression. This was architecture without architects—a community building its own codes from fragments.

When Fujiwara returned to Tokyo, he did so not as a mere consumer of foreign subcultures, but as a cultural conduit. He was, in the oft-cited phrase, the “living internet” before connectivity became digital. By importing records, magazines, and clothing, he acted as a one-man hyperlink, embedding Tokyo youth within a global network of emerging cultural capital. Yet unlike the internet’s later ubiquity, Fujiwara’s network was intentionally scarce, curated, and deeply insider.

Harajuku as the Architecture of Scarcity

At the height of Japan’s luxury obsession, scarcity was not the commodity. Vuitton could be purchased, Chanel acquired, Hermès displayed—each at exorbitant price, but none inaccessible to the expanding Japanese middle and upper classes. In this environment, Fujiwara introduced a radically different model: exclusivity not through price, but through limitation and insider knowledge.

His label GOODENOUGH, launched in 1990, embodied this. The clothes were not mass-produced luxury goods with logos screaming recognition; they were stealth objects, made in small runs, distributed through tightly controlled channels, and understood only by those “in the know.” Ownership was not conspicuous but discreet; the true value lay not in displaying wealth but in signaling cultural literacy.

This was not luxury as commodity—it was luxury as code. A GOODENOUGH t-shirt was less a garment than a key, unlocking access to an insider architecture of meaning. To wear one was to declare membership in a philosophy of scarcity and authenticity, not simply possession of money.

Ura-Harajuku: The Subterranean Blueprint

From these experiments arose what came to be known as Ura-Harajuku—literally, the “back streets” of Harajuku. This was not the glossy Omotesandō boulevard of flagship stores, but the labyrinth behind it, a hidden infrastructure where authenticity was built brick by brick. Ura-Harajuku was an inversion of the luxury maison. Where European brands built marble temples to permanence, Ura-Harajuku operated from cramped basements, narrow alleys, and makeshift storefronts. Yet its influence radiated globally.

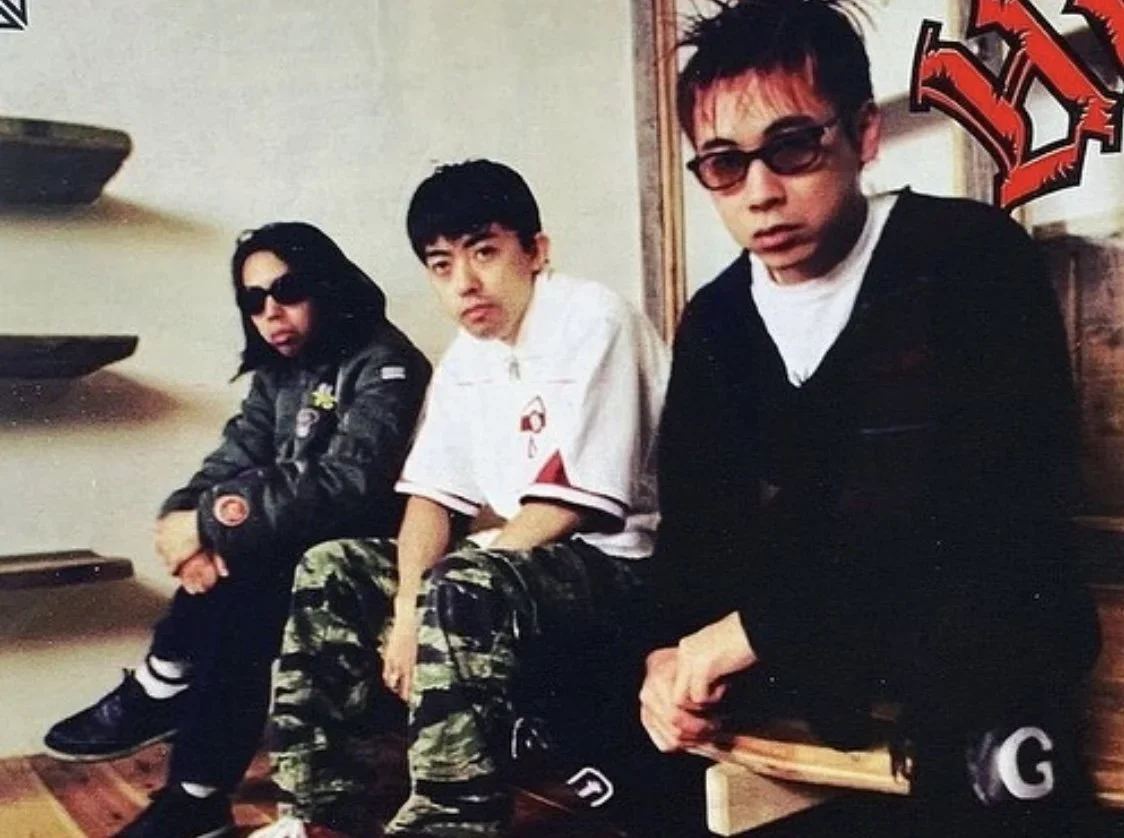

Fujiwara, alongside protégés like NIGO and Jun Takahashi, transformed these spaces into cultural foundries. The NOWHERE store, funded by Fujiwara, was not a boutique in the traditional sense—it was an institute of influence. From its shelves emerged A Bathing Ape and Undercover, brands that would themselves become global architects of style. NOWHERE was both a retail site and a classroom: its curriculum was rebellion, scarcity, and curated authenticity.

This archival photograph captures the exact moment and location your study identifies as the "urban crucible" of post-luxury: the NOWHERE store in Ura-Harajuku, circa 1993. More than just a retail space, this storefront, co-founded by Hiroshi Fujiwara's protégés NIGO and Jun Takahashi, served as the physical "institute of influence" for the entire scene. The group gathered here represents the "invisible network" that Fujiwara architected—a horizontal ecosystem of creators who would go on to define global streetwear, operating from a "subterranean blueprint" that stood as a direct counterpoint to the marble monuments of old-world luxury.

Comparative Framework: Old-World Luxury vs. Harajuku Philosophy

To frame Harajuku as a counterpoint to old-world luxury is not to diminish the craftsmanship of European houses, but to expose the hollowness that scale and repetition had inflicted upon them. Luxury had become formulaic, its codes ossified into predictable monograms and runway cycles.

By contrast, Harajuku introduced what might be called earned authority:

Old-World Luxury: Value as inheritance, encoded in lineage, monogram, and price.

Harajuku Philosophy: Value as initiation, accessed through knowledge, scarcity, and cultural alignment.

Where Vuitton promised permanence through its canvas, Fujiwara’s Harajuku promised transience curated into meaning. Where Chanel offered elegance as repetition, GOODENOUGH offered rebellion as a one-time event.

Harajuku and the Japanese Avant-Garde

Fujiwara’s rebellion cannot be separated from the earlier Japanese avant-garde. Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto had already destabilized Paris with their asymmetrical silhouettes and aesthetic of imperfection. But theirs was still a rebellion staged within haute couture. Fujiwara’s stage was different: asphalt, alleys, and basements. His Harajuku was not Paris-in-opposition but Tokyo-in-invention. It refused validation by Paris entirely, crafting an alternate blueprint for value.

The Semiotics of Scarcity

Here Roland Barthes becomes indispensable. Old luxury communicated through logos—readerly texts, easily legible, endlessly repeatable. Harajuku communicated through absence. Its scarcity demanded participation, interpretation, initiation. A GOODENOUGH drop was not merely purchased—it was decoded. Value became epistemic, not economic.

Japanese Aesthetic Traditions: Wabi, Ma, Iki

Fujiwara’s philosophy resonated with ancient Japanese aesthetics:

Wabi-sabi: imperfection and transience, reflected in Harajuku’s impermanent storefronts.

Ma: the meaningful interval, enacted in Ura-Harajuku’s hidden spaces behind Omotesandō.

Iki: the restrained elegance of discretion, echoed in stealth styling and minimalist logos.

Thus Harajuku was not merely an importation of punk and hip-hop; it was their translation into Japanese philosophy, yielding a hybrid culture at once global and deeply native.

NOWHERE as an Academy of Influence

NOWHERE, founded in 1993, was not just retail but pedagogy. It taught its clientele how to read value differently: not through monogram repetition but through scarcity, through initiation. In doing so, it did not create consumers but disciples, many of whom would go on to architect new global brands. Its structure was rhizomatic, not hierarchical—value diffused through networks rather than descending from above.

Baudrillard and the Weaponization of the Simulacrum

If Vuitton was the simulacrum of aristocracy, Fujiwara’s Harajuku was the simulacrum of initiation. Scarcity was engineered, absence performed, yet both were embraced as authentic. Here Fujiwara anticipated the entire logic of hype culture, where value derives less from material than from ritual scarcity.

The Architecture of Being

Fujiwara’s Harajuku was an act of architecture. Each label, each collaboration, each store was a structural beam in an edifice of influence. His architecture was invisible yet load-bearing, shaping the grammar of value for a generation. Unlike the maison, which built monuments, Fujiwara built systems—ecosystems of intentional scarcity and cultural resonance.

Harajuku as Counterpoint Realized

Harajuku, under Fujiwara’s orchestration, was the first true counterpoint to old-world luxury. It replaced inheritance with initiation, permanence with impermanence, repetition with originality. It proved that value could be authored through scarcity, curated through culture, and sustained through networks rather than monuments.

If Paris gave the world the maison, Harajuku gave the world the ecosystem. And in that ecosystem, Hiroshi Fujiwara became its chief architect—a figure who transformed rebellion into structure, scarcity into philosophy, and the monogram into a cultural imprint.

The Philosophy of Conceptual Functional Art

Hiroshi Fujiwara has often described himself not as a designer but as a “creative.” The statement may sound evasive, but it is in fact a precise articulation of his philosophical stance. To call oneself a designer is to claim mastery over form; to call oneself a creative is to insist that one’s domain is not the object but the condition. In this distinction lies the heart of Fujiwara’s work: his practice is not about producing commodities but about producing contexts, not about designing objects but about architecting meaning.

This is why his career can be understood as the embodiment of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art.

From Conceptual Art to Conceptual Function

The lineage begins with Conceptual Art of the 1960s and 70s. Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, signed “R. Mutt,” redefined art as idea. Joseph Kosuth declared, “Art as idea as idea,” placing the concept above the object. Sol LeWitt’s instruction-based art reduced the artwork to a set of directions, with the object as mere consequence.

Conceptual Art insisted that the material form was secondary; what mattered was the intellectual gesture. But it was often insulated within the art world, dependent on galleries and institutions to frame its radicalism.

Fujiwara extended this principle into the everyday. His Fragment Design does not function as a traditional brand; it is more akin to an idea shop, a consultancy, an archive of taste. A Fragment sneaker, a Starbucks collaboration, a Louis Vuitton bag modified by his sanction—all of these are less about the product than about the gesture of curation. The lightning bolt signifies that the object has been reframed, recoded, philosophically sanctioned.

Where Duchamp placed a urinal in a gallery to elevate it to art, Fujiwara places a lightning bolt on a sneaker to elevate it to cultural artifact. The gesture is homologous: the idea redefines the object.

Yet Fujiwara adds an additional layer: functionality. The object is not merely a provocation; it is meant to be worn, carried, consumed. It enters life not as an artwork to be contemplated but as an artifact to be lived. This is what makes it Conceptual Functional Art.

The Post-Luxury Condition

To understand Fujiwara’s place within this lineage, one must also understand the condition of post-luxury. Luxury in its old form was built on craft, lineage, and monogrammed repetition. Its promise was permanence—objects designed to last, maisons designed to endure.

But by the late twentieth century, this promise had been hollowed by scale. Logos became wallpaper; monograms lost meaning through endless repetition. Luxury was no longer aura; it was ubiquity.

Post-luxury is the response to this collapse. It values discretion over display, scarcity over scale, narrative over inheritance. Its objects are intentionally under-branded, produced in small runs, and curated for the initiated. In post-luxury, what matters is not the price tag but the story, resonance, and sanction embedded in the object.

Fujiwara is one of the earliest and clearest architects of this condition. His Fragment collaborations embody the discreet authority of post-luxury: a lightning bolt that whispers to the in-the-know rather than screaming to the crowd. His refusal to scale Fragment into a global empire is not abdication; it is philosophy. To expand would be to dilute; to remain small is to preserve meaning.

Curation as Creative Act

Fujiwara’s most radical move is to place curation at the center of creation. In traditional models, curation is secondary: the museum curates the artist, the retailer curates the designer. Fujiwara collapses this distinction. His work is to curate—ideas, aesthetics, collaborations—and in this act, creation occurs.

A Fragment sneaker is not original in form; it is a curated mutation of an existing Nike silhouette. A Fragment Vuitton bag is not a wholly new object; it is a sanctioned reframing of Vuitton’s archive. Fujiwara does not need to invent from nothing because invention itself is redefined: not genesis but recontextualization, not originality but intentionality.

This is what makes his practice philosophical. He reveals that in the post-luxury condition, creation is not about making but about marking. The mark—the lightning bolt—is enough. It transforms the object into an artifact of cultural resonance.

The Refusal of Empire

Every choice Fujiwara has made reinforces this philosophy. He could have built Fragment into a global label, with stores, factories, and fashion shows. Instead, he chose the refusal of empire. Fragment remains deliberately small, a consultancy with only a few employees, producing sporadically, collaborating constantly.

This refusal is not hesitation; it is strategy. Empire requires repetition, scale, permanence. Fujiwara’s authority requires discretion, scarcity, impermanence. His power is preserved precisely because it is not overextended. Like an architect who refuses to build skyscrapers in order to preserve the purity of form, Fujiwara limits himself to preserve meaning.

Collaboration as Medium

In this philosophy, collaboration is not a tactic but a medium. Traditional brands treat collaboration as marketing: a way to reach new demographics. Fujiwara treats collaboration as art form. Each partnership—Nike, Vuitton, Starbucks, Pokémon—is a deliberate collision of codes, an opportunity to reframe objects and expand cultural meaning.

The brilliance of Fujiwara’s collaborations lies in their paradoxical balance: they inject authenticity into global corporations while simultaneously preserving his own independence. He lends Nike credibility in the world of streetwear; Nike lends him global scale. Yet Fragment never becomes subordinate; it remains the arbiter, the stamp of approval.

Thus collaboration becomes Fujiwara’s building material. Where an architect uses stone or steel, Fujiwara uses collaboration, constructing networks of meaning that span industries and continents.

Philosophy as Everyday Life

The final hallmark of Fujiwara’s practice is the dissolution of the boundary between art, design, and life. A sneaker, a t-shirt, a coffee cup—all become canvases for philosophy. The object is not exalted above life but inserted into it, embedding meaning into the everyday.

This recalls the Japanese concept of shibumi—the understated elegance that lies not in grand gestures but in the quiet perfection of the ordinary. Fujiwara does not transform life into art; he reveals that life already contains art, if one curates with intention.

Conceptual Functional Art as Blueprint

Hiroshi Fujiwara stands as the prototype of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. He takes the intellectual lineage of Conceptual Art, grounds it in the functional objects of everyday life, and frames it within the condition of post-luxury. His work is not empire but ecosystem, not monument but network.

The lightning bolt monogram is the clearest expression of this philosophy: a minimalist mark that functions not as decoration but as sanction, a discreet confirmation of intentionality. It is art as idea, design as curation, life as canvas.

Through this philosophy, Fujiwara has redefined what it means to create in the modern world. He has shown that true influence lies not in the object but in the system, not in the empire but in the architecture of meaning.

The Monogram as a Creative Thumbprint

Monograms are among humanity’s oldest signatures of permanence. From medieval signets to the gilded letters of Louis Vuitton and Gucci, the monogram has always functioned as a code of inheritance. It is a condensation of history into ornament, a cipher of continuity that transforms fabric into heraldry. To own an object bearing a monogram is to be inducted into its lineage, to carry the weight of permanence in one’s hand.

Fujiwara’s Fragment Design lightning bolt is at once continuous with and radically different from this tradition. It is, in its form, a minimalist icon—two strokes of electricity enclosed in a circle. It carries none of the ornate flourishes of dynastic crests, no initials of founders, no reference to family lineage. Instead, it functions as what might be called a creative thumbprint: a mark of sanction, a discreet sign that an object has passed through Fujiwara’s architecture of influence.

The Traditional Monogram: Inheritance as Authority

The old-world luxury monogram was a condensation of dynastic permanence. The interlocking L and V of Louis Vuitton, conceived in the nineteenth century, was both a visual code and a defensive measure against counterfeit. The double C of Chanel was a condensation of Gabrielle Chanel’s personal initials into an emblem of maison authority. These marks did not simply decorate; they signified inheritance. To carry them was to carry the aura of lineage, a chain of continuity stretching from founder to consumer.

The promise was permanence. The maison assured that its codes would outlive generations, that the monogram would persist across time, weathering trends and upheavals. It was less a logo than a secular sacrament, a visual oath binding object to house, consumer to legacy.

The Lightning Bolt: Authority Without Lineage

Travis Scott x Fragment Design x Air Jordan 1 High “Military Blue”

Fujiwara’s lightning bolt operates by a different logic. It does not represent inheritance but earned authority. It is not tied to a family crest, nor to a dynastic lineage. It is tied instead to Fujiwara’s reputation as a tastemaker, a curator, a cultural architect. Its authority does not descend from the past but radiates from the present.

Where the Vuitton monogram insists, “I belong to a house,” the Fragment lightning bolt whispers, “I belong to a code.” The former derives power from permanence; the latter derives power from discretion.

It is, in essence, the post-luxury monogram: not inheritance, but sanction; not lineage, but intentionality.

The Semiotics of Discretion

Logos, in the old model, were proclamations. They shouted across handbags and trunks, asserting identity through repetition. The Fragment lightning bolt does the opposite: it conceals itself, often rendered small, monochrome, even hidden within seams. It requires initiation to recognize.

This is semiotics by discretion. The bolt is valuable precisely because it is not universally legible. Its authority is strongest among the initiated, those who know its history, its scarcity, its philosophical weight. In this sense, the bolt is less a logo than a shibboleth—a code that separates those inside the circle from those outside it.

The Philosophy of the Thumbprint

Why call it a “thumbprint”? Because unlike a monogram, which represents lineage, a thumbprint represents individuality. It is the trace of a singular presence, a unique mark left upon the world. Fujiwara’s bolt functions as such: a mark of his presence, a trace of his sanction.

Yet the thumbprint metaphor also carries philosophical weight. A thumbprint is not designed, not ornamental; it is the residue of contact, the impression of touch. Similarly, the Fragment logo signifies not authorship in the sense of creation, but authorship in the sense of contact. Its presence declares: this object has passed through Fujiwara’s hands, through his aesthetic, through his code.

The logo is not a claim of ownership but a declaration of curation.

From Insider Rebellion to Global Symbol

The Fragment bolt was not always globally recognized. In its earliest incarnation as the mark of Electric Cottage, it appeared on goods produced for Fujiwara’s close circle of friends, released in tiny runs with sporadic timing. It was, at that stage, a mark of intimacy, an insider’s symbol.

With the founding of Fragment Design in 2003, the bolt expanded its scope, becoming the recurring emblem across Fujiwara’s collaborations. Nike sneakers, Louis Vuitton bags, Starbucks mugs, Pokémon merchandise—all carried the lightning bolt, and with it, the aura of Fujiwara’s sanction.

But here lies the paradox: the more the bolt appeared, the more it risked the fate of the old monograms it once countered. What began as a symbol of rebellion and scarcity is now pursued as a collectible, a status symbol, a token of conspicuous consumption. The Fragment x Jordan 1 sneaker, released in 2014, became one of the most coveted sneakers of the decade, reselling for thousands of dollars—a far cry from the discreet rebellion of its origins.

The Risk of Co-option

This shift poses a philosophical question: can a symbol of discretion survive global visibility? Can a monogram designed to whisper remain powerful once it is made to shout?

Here Fujiwara’s strategy of refusal becomes critical. He does not overproduce, does not flood markets, does not scale Fragment into a global brand. He preserves the bolt’s aura by keeping its releases erratic, its presence understated, its meaning bound to his sanction. Even when the bolt enters the mainstream, its logic remains intact: it signals not mass appeal but curated intent.

This is the resilience of the creative thumbprint. Unlike the dynastic monogram, whose power depends on repetition, the Fragment bolt thrives on scarcity, discretion, and curated presence. Its authority is sustained not by how often it appears but by how rarely it is sanctioned.

The Monogram as Cultural Imprint

Ultimately, the Fragment bolt must be understood as a cultural imprint. It is not merely a logo, nor even a brand mark, but a structural element in Fujiwara’s architecture of influence. It condenses his philosophy into a single sign: discretion, scarcity, initiation, sanction.

If the old-world monogram was the ornament of permanence, the Fragment bolt is the imprint of intentionality. It transforms the object into an artifact not of lineage but of resonance. It tells the initiated not “this is expensive” but “this is sanctioned.”

In this, Fujiwara redefines the very function of the monogram. It is no longer about inheritance but about authorship, no longer about permanence but about resonance. The lightning bolt is less a logo than a philosophy in miniature: a mark that encodes an entire worldview.

The Cultural Expander: A Bridge of Influence

Influence, in its most profound form, is never static. It is not the possession of authority but its distribution, not the building of monuments but the construction of bridges. Hiroshi Fujiwara’s genius lies not only in curating codes of meaning but in expanding them across contexts without dissolving their integrity. His medium for this expansion is the collaboration.

Where traditional designers sought control, Fujiwara sought collision. Where maisons policed their borders, Fujiwara crossed them. His career can be mapped through a constellation of collaborations—each one a structural beam extending his architecture of discretion into new domains. Through them, he became the prototype of the cultural expander: a figure who dissolves boundaries between subculture and luxury, between niche and mass, between art and commerce.

Collaboration as Architectural Medium

Maserati Ghibli Modena Q4 Fragment

In fashion, collaboration was once an anomaly. It was tolerated as occasional marketing, a way to generate novelty. By the late 1990s, it had become a tactic. By the 2000s, it was formula. Today, it is the foundation of global streetwear and luxury alike.

Fujiwara did not invent collaboration, but he redefined it. For him, collaboration was never gimmick; it was material. Like stone to the architect, collaboration was his building block. Each project was not an isolated event but part of a structural logic: a bridge connecting disparate worlds, a node in an expanding network of cultural resonance.

Through collaboration, Fujiwara extended his discreet authority outward, embedding his philosophy into global corporations while preserving his own independence. He never surrendered the lightning bolt; he inscribed it onto new terrains.

Nike: Sneakers as Cultural Artifact

Htm Air Force 1 'Fragment'

Fujiwara’s collaboration with Nike remains one of the most important chapters in the history of modern fashion. Long before the “hype drop” era, he understood that sneakers were not athletic gear but cultural artifacts. His early Nike collaborations—like the HTM line, produced alongside Mark Parker and Tinker Hatfield—treated the sneaker not as product but as philosophy.

The Fragment x Air Jordan 1, released in 2014, became one of the most coveted sneakers of the decade. Its value was not in material rarity but in symbolic sanction: the lightning bolt transformed the Jordan from a commodity into a cultural relic. Resale prices soared into the thousands, yet the true currency was not money but aura.

Through Nike, Fujiwara globalized the logic of post-luxury conceptual functional art. He showed that scarcity, discretion, and sanction could transform even the most mass-produced objects into carriers of cultural meaning. Nike, in turn, adopted this playbook as corporate strategy, building its empire of “drops” on the template Fujiwara had modeled.

Louis Vuitton: Sanctioning the Collision

Louis Vuitton x fragment design Collection 2017

If Nike represented Fujiwara’s expansion into mass culture, Louis Vuitton represented his sanctioning of the collision between streetwear and luxury. Long before Virgil Abloh would make the fusion explicit, Fujiwara’s Fragment x Louis Vuitton collaboration (2017) re-coded the maison’s heritage through the lightning bolt.

It was a gesture both radical and understated. Vuitton’s monogram, the very emblem of old-world permanence, was reframed through Fujiwara’s discreet thumbprint. The collaboration declared: streetwear had not only arrived at luxury’s gates but had been given sanction within its walls.

This was more than a collection; it was a philosophical event. Fujiwara positioned himself as the translator between codes, the bridge that allowed youth culture and aristocratic luxury to speak a common language. His authority was not diminished by Vuitton’s grandeur; rather, Vuitton’s grandeur was re-contextualized by his discretion.

Starbucks: The Everyday as Canvas

If Nike and Vuitton represented global giants of sport and luxury, Fujiwara’s collaboration with Starbucks represented a different frontier: the banality of the everyday. A coffee cup is the most mundane of commodities, produced in astronomical quantities and discarded daily. By placing the lightning bolt on it, Fujiwara revealed that even the banal could be re-coded.

This was philosophy at its most radical: the everyday as canvas. By embedding meaning into the disposable, Fujiwara collapsed the hierarchy between high and low, rare and common. A coffee cup could carry as much cultural resonance as a Vuitton trunk, provided it bore the thumbprint of sanction.

Pokémon and Moncler: The Expansion of Play

Other collaborations pushed the logic further. With Pokémon, Fujiwara entered the realm of play and nostalgia, re-framing childhood icons through his minimalist code. With Moncler, he entered the alpine world of technical luxury, embedding Fragment’s discretion into outerwear designed for the extremes.

Each collaboration extended his architecture into new terrains, proving that the logic of discretion and sanction could operate across any medium—sneaker, handbag, coffee cup, cartoon character, ski jacket. The object was irrelevant; the philosophy was consistent.

Here, Fujiwara’s role as a cultural expander is perfectly illustrated. This black Pikachu plush, a centerpiece of the Fragment Design x Pokémon “Thunderbolt Project,” shows his architectural logic expanding into the realm of global nostalgia. By applying his minimalist "creative thumbprint" to one of the world's most recognizable childhood icons, Fujiwara recodes the object entirely. It ceases to be just a toy and becomes an artifact of post luxury conceptual functional art, demonstrating that his philosophy of sanction and discretion can be embedded into any medium, even the world of play.

The Bridge of Translation

What unites all of Fujiwara’s collaborations is his role as a bridge of translation. He translates the language of subculture into the idiom of luxury, the logic of luxury into the everyday, the aesthetic of scarcity into the context of mass production. His power is not in owning either side but in enabling their dialogue.

This bridging is not dilution but expansion. He does not water down subculture for the mainstream, nor does he inflate luxury for the street. He builds a bridge sturdy enough for both to cross, preserving the integrity of each while creating new meaning in their intersection.

The Cultural Expander

Through his collaborations, Fujiwara has expanded discreet authority into global resonance. He has shown that influence need not depend on empire but can radiate through networks, bridges, and collisions. Each collaboration is not an act of compromise but of architecture: a beam extending his structure, a span connecting otherwise disparate worlds.

He is, in this sense, the quintessential cultural expander. Where others built monuments, he built bridges. Where others sought empire, he sought resonance. The Fragment bolt is the passport that allowed him to cross worlds, embedding philosophy into sneakers, handbags, coffee cups, and cartoons alike.

In doing so, Fujiwara did more than collaborate; he redefined collaboration itself. He turned it into a medium, a philosophy, a structural tool of cultural architecture. And through it, he expanded not only his own influence but the very boundaries of what culture could become.

Legacy: The Intentionality of Influence

Every career leaves artifacts. Designers leave archives; corporations leave empires; dynasties leave monuments. Hiroshi Fujiwara leaves none of these in the traditional sense. His Fragment label has no sprawling archives, no flagship stores, no gilded headquarters. His work, dispersed across collaborations and drops, is often ephemeral, released in small numbers and quickly consumed. And yet, paradoxically, his legacy feels more enduring than that of many who built empires.

The explanation lies in his intentionality. Fujiwara’s career is not a random sequence of collaborations, nor a string of opportunistic ventures. It is an architecture carefully constructed to sustain itself without requiring permanence of object. His true legacy is not the product but the system—the blueprint of how influence can be engineered in the post-luxury condition.

Ephemerality as Structure

Fujiwara’s genius was to embrace ephemerality not as weakness but as structure. Sneakers sell out in minutes, coffee cups are discarded, t-shirts fade. None are built to last in material terms. Yet their meaning persists, because each is embedded in the architecture of Fujiwara’s sanction.

This is permanence through transience. The lightning bolt’s authority does not depend on its continuous presence but on its cumulative aura. Each drop reinforces the code; each collaboration adds another beam to the structure. The products vanish, but the architecture of meaning remains.

Where old-world luxury sought eternity through durability of material, Fujiwara achieves eternity through durability of philosophy.

The Blueprint of Discipleship

One of the clearest indicators of Fujiwara’s legacy is the network of disciples he has nurtured. NIGO, founder of A Bathing Ape and later Human Made, was directly mentored by Fujiwara in the Harajuku scene. Jun Takahashi, founder of Undercover, likewise found early support through Fujiwara’s circle. Even Virgil Abloh, though not a direct disciple, acknowledged Fujiwara as a template for blending streetwear with luxury.

This is legacy not as monument but as multiplication. By mentoring others, Fujiwara ensured that his philosophy would propagate beyond himself. His architecture is not a single building but a city of structures, each designed by those he influenced. The discipleship model ensures continuity not through inheritance but through iteration.

This iconic archival photograph is the literal embodiment of Fujiwara’s "blueprint of discipleship." It captures the architect himself (right) alongside his two most prominent protégés, Jun Takahashi (left) and NIGO (center). This image perfectly visualizes the legacy your study defines: not a static monument, but a dynamic, horizontal "network of disciples." By mentoring this next generation, Fujiwara ensured his philosophy would propagate and be iterated upon, creating an invisible architecture of influence that long outlives any single object.

Intentional Scarcity as Permanence

Scarcity, in Fujiwara’s model, is not a tactic but a philosophy. By refusing to scale, by producing in limited runs, by embedding discretion into every release, he ensured that each object carried weight disproportionate to its material presence. This intentional scarcity is the reason his collaborations are remembered long after the products themselves disappear.

Scarcity is permanence in disguise. A Fragment sneaker may be resold, lost, or destroyed, but its aura endures in collective memory. Stories of its drop, its price, its sanction circulate endlessly, reinforcing Fujiwara’s presence even in absence. His legacy is thus woven into narrative as much as object.

The Architecture of Codes

At its core, Fujiwara’s legacy is the creation of a code. The Fragment lightning bolt is not just a logo but a cipher of meaning: discretion, sanction, initiation, scarcity. This code does not require Fujiwara’s continuous authorship; it has become self-sustaining. Even if he were to stop producing tomorrow, the bolt would continue to resonate, its meaning embedded in culture itself.

This is the ultimate form of intentionality: to create something so structurally sound that it survives without its architect. It is the architectural equivalent of a building designed not only to stand but to outlive its maker. Fujiwara has built such a code, a monogram that functions as cultural imprint long after the object fades.

Legacy as Prototype

Fujiwara’s true legacy is not Fragment, nor Nike, nor Vuitton. It is the prototype of how influence can be constructed in the 21st century. He showed that one does not need empire to endure, nor mass production to matter. One needs only intentionality—consistency of philosophy, discretion of sanction, and architecture of networks.

Future cultural architects will follow this blueprint. Already we see echoes: the discreet drops of Human Made, the curated scarcity of Fear of God, the architectural collaborations of Off-White. All trace, directly or indirectly, to Fujiwara’s model of intentional influence.

The Architecture That Survives

Hiroshi Fujiwara’s legacy is not an archive but an architecture, not an empire but a code. He has proven that permanence does not require stone, fabric, or leather. It requires intentionality. By building a system of meaning—discretion, sanction, scarcity—he has created an architecture that survives even when its objects vanish.

This is the intentionality of influence: to construct a framework so resonant, so coherent, that it outlives the moment, the trend, the object, even the architect himself. In this, Fujiwara has secured not only his own legacy but a blueprint for the future of cultural creation.

New Blueprint for Influence

To study Hiroshi Fujiwara is to study not a career but an architecture of being. His life’s work cannot be contained within shoes, t-shirts, or coffee cups. These are only artifacts, shadows of a deeper construction. What Fujiwara built is invisible but enduring: a structure of codes, a philosophy of discretion, an ecosystem of influence.

The traditional models of cultural authority were vertical. Dynasties built empires. Maisons built permanence through archives, ateliers, and armies of stores. Their monograms shouted across canvases of leather and silk, insisting on inheritance as the guarantee of value.

Fujiwara inverted this architecture. He built horizontally, not vertically. His influence spread not through empire but through network, not through scale but through sanction. He chose discretion over spectacle, scarcity over ubiquity, intentionality over inheritance. His Fragment Design bolt functions not as decoration but as imprint, not as ornament but as philosophy.

In doing so, he revealed a new model for cultural authority — one that does not depend on permanence of material but on permanence of meaning.

The Post-Luxury Prototype

Fujiwara is the prototype of the post-luxury condition. In a world where traditional luxury has hollowed itself through scale and repetition, he embodies an alternative: value derived not from lineage but from resonance, not from empire but from intentionality. His lightning bolt is not a claim to heritage but a confirmation of taste, a discreet whisper that sanctions the object it touches.

This is luxury redefined: not possession of the rare but initiation into the resonant. Not the loud inheritance of dynasty, but the quiet authority of discretion.

Influence as Architecture

What endures in Fujiwara’s work is not the object but the intentionality. To make something with Fujiwara is to make something on purpose. Each gesture is calculated, each collaboration chosen, each mark placed with deliberation. This intentionality is itself the legacy: the insistence that meaning is not accidental, that influence can be engineered with the precision of architecture.

It is this that future cultural architects inherit — not a brand, not a logo, but a blueprint.

The New Blueprint for Influence

In the end, Fujiwara’s lesson is clear: the age of empires is over. The age of intentional architectures has begun. Influence is no longer secured by repetition, lineage, or spectacle. It is secured by discretion, scarcity, sanction, and the ability to embed philosophy into the everyday.

This is the new blueprint for influence:

Build networks, not monuments.

Create codes, not commodities.

Value discretion above display.

Engineer scarcity as permanence.

Embed philosophy into the everyday.

Fujiwara’s architecture shows us that culture itself can be designed as carefully as a building, that influence can be constructed beam by beam, code by code, until it becomes invisible, inevitable, enduring.

He has proven that the monogram, once the emblem of dynastic permanence, can be reinvented as a creative thumbprint — a cultural imprint that encodes philosophy rather than heritage, intentionality rather than inheritance.

The Permanence of Meaning

Hiroshi Fujiwara is not a designer in the conventional sense. He is not even, properly speaking, a brand. He is an architect of influence, a cultural synthesist, a builder of invisible structures. His work demonstrates that the most powerful force in modern culture is not spectacle but sanction, not empire but architecture, not permanence of object but permanence of meaning.

His legacy is the revelation that culture itself can be monogrammed — not with initials, but with intention. And that, once imprinted, such a mark needs no outside code to survive.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.