The Sublime Silence: Tadao Ando's Architecture of Light, Material Purity, and Existential Form

Tadao Ando, the self-taught Pritzker Prize-winning architect. His work, characterized by minimalist form and the use of Béton Lissé, pursues a "Zero-Degree Aesthetic" rooted in Zen philosophy and the pursuit of the architectural sublime.

Tadao Ando’s architecture is not merely built; it is sculpted from shadow and stillness. Across his body of work, from the hallowed interior of the Church of the Light to the severe elegance of his museums and private residences, the autodidact architect offers a confrontation more profound than any decoration: the sublime silence. This study examines how Ando achieves an absolute architectural void, mirroring the non-objective quest of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square , by aggressively stripping away all inessentials. The signature medium, concrete—meticulously poured to a pristine finish—is employed as a monolithic canvas for the immaterial forces of light and time. Yet, this radical simplicity reveals a deep cultural irony: born from the socially aggressive honesty of Brutalism , Ando’s uncompromising aesthetic has become the definitive code of Post-Luxury, where austerity and technical perfection denote the highest level of affluence. To occupy an Ando space is to submit to a moral architecture, one where the pure material structure forces a visceral engagement with the materiality of existence, the passage of time, and the fundamental elements of the lifeworld.

The Pursuit of the Absolute: Ando, Malevich, and the Zero-Degree Aesthetic

Silence, Reduction, and the Architectural Sublime

Tadao Ando’s architecture operates at an intersection of Eastern spiritual reductionism and Western modernist radicalism, forging an aesthetic condition that transcends mere structure to invoke the architectural sublime. This pursuit of material purity and radical simplicity forms the basis of a Post-Luxury aesthetic, forcing occupants into an existential engagement with space and time. This sublime quality, however, does not align with the traditional Burkean understanding of overwhelming terror or colossal scale. Instead, Ando achieves a form of the Kantian mathematical sublime—a confrontation with vastness or infinity attained through profound material and spatial emptiness, a condition often referred to as the "void".

This reductive methodology initiates what may be termed the "Zero-Degree Aesthetic," a strategic stripping away of non-essential components to define the "true essence of any given architectural element". By eliminating ornament and complex finishes, Ando compels the occupant to engage directly with the foundational elements of existence: light, space, and time. The structural reduction is purposeful; the resultant conceptual absence, achieved by minimizing external aesthetic distraction , creates a perceptual void. The mind, lacking traditional external input, is forced to confront its own limits and the scale of elemental forces, generating an intense, internal spiritual experience—the Sublime Silence. This pursuit of the absolute through radical aesthetic reduction places Ando’s work in direct conceptual alignment with the breakthrough achieved by early 20th-century abstract art.

Malevich's Black Square (1915) and the Non-Objective Feeling

Kazimir Malevich's Black Square (1915). This painting inaugurated the Zero-Degree Aesthetic in art, seeking the "minimalist pursuit of the sublime" through absolute reduction. It functions as the two-dimensional parallel to Ando’s architectural Suprematism.

The conceptual foundation of Ando’s reductive architecture finds its closest analogue in Kazimir Malevich’s seminal work, Black Square (1915). Malevich’s painting is recognized as the pivotal moment of non-objective art, where the canvas divorced itself from representation to focus purely on profound sensation and feeling. This painting represents the ultimate "minimalist pursuit of the sublime" in a two-dimensional format.

Ando functions as an Architectural Suprematist, employing rigorous, abstract geometric forms—the perfect cube, the unadorned plane—while aggressively rejecting decorative ornament. Just as Malevich rejected pictorial illusionism, Ando rejects architectural superficiality. His vast concrete wall becomes the architectural equivalent of Malevich's canvas: a monolithic surface intended not to bear images or symbols, but to capture and frame profound sensation. This wall is a boundary condition, establishing the material limit against which the immaterial forces of light and atmosphere are measured

The Contradictions of Concrete: Brutalism’s Social Ethos vs. Ando’s Purity

Ando’s signature material, unadorned concrete, draws its lineage from the Brutalist tradition, which itself emerged from modern architecture's philosophy of "truth to materials." This philosophy mandates the raw expression of materials, often achieved by exposing the building’s components, including its frame, sheathing, and the construction methods used, such as the seams imprinted by the formwork.

However, the application of béton brut reveals a critical philosophical divergence. Classic Brutalism was often characterized as socially progressive and aggressive, concerned with structural honesty and economic necessity. Ando, conversely, transforms this material into a pristine, silent backdrop suitable for meditative or spiritual events. While the construction marks remain visible, acknowledging the material's origin , the overall surface is elevated to

Béton Lissé—a meticulously perfect concrete. This refinement signifies an aestheticization of material truth. The material's raw honesty, originally driven by socialist or functional concerns, is now achieved through specialized, high-cost labor and immense technical precision, transitioning from a functional necessity to a cultural marker that sets the stage for the exploration of Post-Luxury aesthetics.

Material Purity, Time, and the Wabi-sabi Foundation

The Ontology of Concrete: Béton Lissé as a Spiritual Membrane

Ando’s concrete structures are defined by an intense material discipline. The meticulous casting process results in a seamless, reflective surface that sits ambiguously between the rough texture of true béton brut and the polish of highly finished stone. Crucially, the process ensures that the visibility of the construction marks, derived from the formwork, is maintained.

The unadorned material functions as a temporal marker. Lacking paint, cladding, or other protective finishes, the surface is forced to directly absorb and reflect atmospheric phenomena. It registers moisture, reflects the precise intensity of light, and visibly exhibits the passage of time through staining, patina, and weathering. This intentional exposure forces occupants into an uncomfortable, yet profound, engagement with the materiality of their own existence and the inevitable passage of time—a confrontation mandated by the very structure surrounding them. The material, designed to age and show wear, thereby functions as a controlled ruin. Unlike standard modern construction which seeks perpetual newness, Ando’s work is intentionally vulnerable to the elements, acting as a permanent, palpable reminder of human finitude and the existential confrontation with decay, turning the building into a living, temporal monument.

Wabi-sabi: Embracing Impermanence and Incompleteness

The philosophical justification for Ando’s austere reductionism is deeply anchored in the Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-sabi. This philosophy embraces the beauty inherent in things that are "imperfect, impermanent and incomplete," placing it as a direct antithesis to the "classical Western notion of beauty as something perfect, enduring and monumental".

Ando’s architectural vision aligns precisely with this ideology, seeking a "simple aesthetic that grew stronger as inessentials were eliminated and trimmed away". This elimination is not merely stylistic but constitutes a moral and spiritual imperative rooted in Zen thought. By eliminating ornament and extraneous detail, the concrete wall is elevated from a decorative object to a functional, pure plane for necessary sensory and spiritual interaction. This pursuit of simplicity and the removal of distractions suggests that the aesthetic reduction itself is intended as a moral practice, designed to "reshape societal values". The resulting starkness, characterized by humble, unadorned concrete, contributes to the creation of a darker, more "meditative place of worship" , where the moral function of the building is achieved through the intentional sensory deprivation it imposes.

Existential Form and the Phenomenological Experience

A Critique of Rational Modernity and the Lifeworld

Ando’s work is fundamentally a critique of the spatial and philosophical limitations of rational and functional modern architecture. He argues that modernity became "detached from nature and experiences," losing the vital connection to the "true feelings of life, the breeze of the wind and the sound of the rain". This reduction of architecture to "spatial organizations and the numerical imperatives" neglects the perceptual dimensions of the human experience.

To restore this sense of the lifeworld (the pre-reflective, sensory world), Ando adopts abstract geometric forms but integrates them with the "daily activities of man". This phenomenological approach emphasizes the subjective, bodily experience, aiming to enable people to experience the space with their bodies rather than solely through rational analysis. By moving beyond numerical efficiency toward emotional and spiritual issues, Ando seeks to re-establish the essential connection to natural sensations and experiences.

Light as the Absolute and the Dematerializing Void

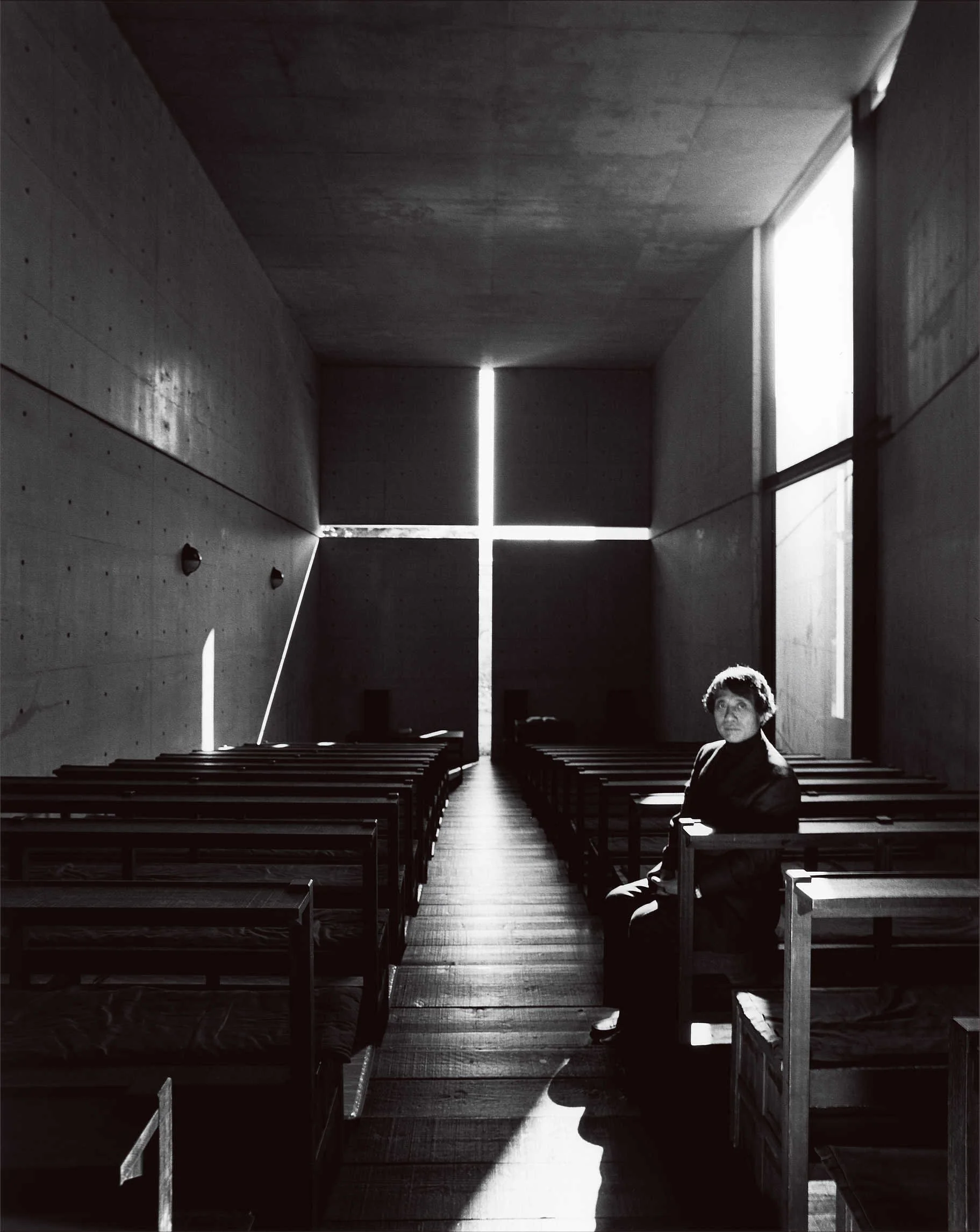

Interior of the Church of the Light (1989), Ibaraki, Osaka. The simple, cruciform void cuts into the Béton Lissé, creating an "immaterial cross" of light that profoundly embodies the concept of the dematerializing void and the architectural sublime.

The central mechanism by which Ando achieves existential meaning is the manipulation of light. His structures explore duality: solid/void, light/dark, stark/serene. Light is not treated as a mere source of illumination but as an active, sacred architectural element.

The Church of the Light (1989) is the definitive case study in this approach. The design is rigorously reductive, stripping the space of nearly all traditional religious paraphernalia, leaving a structure often criticized as disturbingly empty and undefined. The critical element is the simple cruciform extrusion—a void cut directly into the east-facing concrete facade. The cross is defined entirely by light pouring into the interior. This intentional absence creates an immaterial cross, functioning as an absolute void of light. This light has a "dematerializing effect" on the interior walls, perceptually changing the dark concrete volume into an "illuminated box," transforming "material into immaterial".

The light within these structures is not static; it is embodied temporality. Because the walls are pristine and unadorned, the movement of the sun across the surface becomes the primary aesthetic event. Occupants are compelled to perceive the inexorable passage of time not intellectually, but physically through the moving shadow lines and changing intensity of light. The ephemeral nature of light, constantly shifting, aligns the zero-degree aesthetic with the impermanence mandated by Wabi-sabi.

The Five-Senses Design Mode (Gokan-Sekkei) and Bodily Awareness

Ando’s design syntax, often summarized as a "Five-Senses Design Mode," aims for "mental consonance and inspiration" between the individual spirit and the architecture. The conciseness and interaction of geometric shapes are designed to invoke Zen thought.

This emphasis on sensory primacy means the design compels intense, bodily engagement with the space , heightening the occupant's awareness of the intersection of the "spiritual and secular within themselves". In the Row House (Azuma House) in Osaka, Ando encapsulated an open courtyard within a severe, raw concrete box set into the dense urban fabric. By inserting nature into the harsh environment, he forces occupants to co-exist with natural elements (rain, wind, sun). This intentional inconvenience critiques the isolation and "alienation of modern life" , demonstrating architecture’s power to reshape societal values by mandating simplicity and introspection.

The use of abstract geometric forms within a severe concrete envelope leads to a condition of therapeutic isolation. By creating an intentionally “void” space, stripped of conventional decorative or symbolic cues , cultural noise is eliminated. This architectural concision compels introspection, acting as a potent antidote to modern alienation. The structure deliberately forces a confrontation with the self as the only valid object of focus.

Essential Contrast: Rational vs. Existential Focus

Ando's architectural intent provides a clear critique of the priorities upheld by rational modern architecture. Where the latter focused on functional organization, numerical imperatives, and efficient spatial layout, Ando’s work focuses on evoking emotional and spiritual issues, achieving mental consonance, and promoting a rich bodily experience. This divergence is equally pronounced in the relationship to nature. Rational modernity often treats nature as a detached exterior element or a calculated view, while Ando demands an integral connection, emphasizing the "true feelings of life, the breeze of the wind, and the sound of the rain". Aesthetically, rational modernism adheres to the classical Western notion of beauty—something perfect, enduring, and monumental—whereas Ando aligns with

Wabi-sabi: valuing the imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete, achieved through the elimination of inessentials. Finally, in terms of material usage, rational modern architecture favors standardization, cladding, and smooth finishes, contrasting sharply with Ando’s pursuit of material purity and "truth to materials" (Béton Brut), including the raw exposure of seams.

The Post-Luxury Paradox and Cultural Commodification

Austerity as Affluence: The Post-Luxury Aesthetic Code

Detail of a Béton Lissé wall. The refined, meticulous casting process elevates the material from functional Brutalism to an aesthetic marker of Post-Luxury affluence. This surface, vulnerable to weathering, embodies the Wabi-sabi philosophy of embracing time and impermanence.

Tadao Ando's aesthetic purity, born from spiritual and moral imperatives, has inadvertently positioned his work at the pinnacle of Post-Luxury design. Post-Luxury is defined by the rejection of overt branding, material excess, and visual complexity, favoring instead extreme simplicity, material honesty, and impeccable—but often invisibly costly—craftsmanship.

The "supreme irony" inherent in Ando’s status is that his architecture, derived from Brutalism—an aesthetic historically linked to socially aggressive and progressive movements —is now sought out by the global cultural elite. He has become the "billionaire's go-to architect," as evidenced by commissions from figures such as François Pinault, the owner of major luxury goods companies. This adoption highlights that the severe simplicity of Ando’s forms is not economically frugal. The elimination of visual inessentials demands an escalation of technical precision, notably the specialized, high-cost labor required for his flawless Béton Lissé. The cost of purity is thus inversely proportional to its visual complexity.

The Commodification of Silence: Exclusive Introspection

The austerity of Ando’s design functions as an exclusive aesthetic code. In a world saturated with visual noise, decoration, and branding, the absolute absence of these elements becomes the ultimate scarce commodity. The concrete structure, void of ornament, offers a financially exclusive silence because it requires absolute control over the environment, the process, and the material finish. This "Sublime Silence" signifies that the owner possesses the superior cultural capital necessary to appreciate experiential and philosophical depth over material display.

For the affluent patron, the commission of a radically simple, materially honest structure signals that they have transcended the need for ostentatious display, valuing existential engagement and quiet contemplation (Existential Form) above tangible assets. This presents a profound paradox: while Ando’s architecture critiques the alienation of modern life and proposes simplicity as a moral antidote, its stringent, high-cost aesthetic often excludes the general public, reserving its spiritual and experiential benefits for private or exclusive cultural spaces. The original moral imperative is structurally inverted into an economic exclusivity, confirming that Post-Luxury functions as a refinement of affluence, substituting spiritual quality for material quantity.

The historical trajectory suggests a philosophical co-option of a radical, socially grounded aesthetic. Brutalism’s principles were intended for democratic expression. When the material philosophy of "truth to materials" is used by the cultural elite to provide spiritual depth, it confirms that Post-Luxury co-opts the vocabulary of austerity to denote superior status.

The Paradox of Purity: Brutalism to Post-Luxury

The transformation of concrete from a democratic, functional material to an exclusive, highly refined aesthetic symbol defines the Paradox of Purity. Classic Brutalist Architecture of the 1950s-70s was typically patronized by the government, universities, and public housing, and was associated with socially progressive goals. Ando’s Post-Luxury aesthetic, however, is commissioned by affluent private clients and cultural institutions, marking it as exclusive and high culture. This shift is mirrored in the material finish: Brutalism employed.

Béton Brut, a rough, honest, and inexpensive finish, while Ando utilizes Béton Lissé, which is pristine, meticulously cast, and consequently expensive. Philosophically, where Brutalism sought democratic expression, cost efficiency, and structural clarity, Ando aims for existential introspection, sensory engagement, and aesthetic rigor. The aesthetic results also diverge: Brutalist buildings were often aggressive, heavy, and criticized as ugly, whereas Ando's work is stark, silent, and refined, though it is occasionally criticized as empty. This entire progression illustrates the co-option of austerity’s vocabulary by contemporary affluence.

The Enduring Tension: The Spiritual Imperative and the Existential Legacy

Tadao Ando’s architectural output is not merely a minimalist style but a rigorous, interdisciplinary quest for the absolute—a “Sublime Silence.” This condition is achieved through the studied tension between radical reductionism and profound elemental presence.

By leveraging the zero-degree aesthetic of Malevich’s non-objective abstraction and grounding it in the material ontology of béton brut , Ando creates spaces designed to provoke an existential response. His commitment to material purity and the elimination of inessentials reflects a deep adherence to the

Wabi-sabi philosophy of impermanence, which is made physically manifest as light (the ultimate ephemeral form) dematerializes the heavy, aging concrete. Through his phenomenological approach, which emphasizes bodily experience and the “Five-Senses Design Mode,” Ando succeeds in criticizing the detachment of rational modernity by forcing occupants to recognize the "true feelings of life, the breeze of the wind and the sound of the rain".

Ultimately, Ando confirms architecture’s power to reshape societal values by demanding profound introspection. Although his aesthetic has been co-opted by the Post-Luxury economy, turning moral austerity into financial exclusivity , the formal power of his structures remains undeniable. The Sublime Silence is the sound of the self, confronting its own limits within a pure, unadorned space defined only by light, material honesty, and the inexorable passage of time.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.