Biopolitics of the Artifact: How Functional Endurance Challenges Foucault, Groys, and the Archival Death Mandate

The modern artifact, particularly one committed to a radical notion of persistence and utility, finds itself embroiled in a hidden conflict with the very institutions designed to preserve it. This conflict is fundamentally ontological and political, operating at the convergence point of archival theory and the management of life itself. The framework of objects committed to continuous functional endurance (PLCFA) is not merely a material standard but a philosophical defense, strategically positioned against the state and institutional power structures that seek to define, contain, and ultimately neutralize the artifact’s narrative duration. To understand the structural necessity of the Custodian’s Contract and permanent digital provenance, one must first dissect the institutional mandates of time and life control, utilizing the critical frameworks established by Boris Groys regarding the Archive and Michel Foucault concerning Biopolitics.

The Institutional Necropolis: Groys’s Archive and the Death of the Functional Object

The concept of institutional preservation, superficially an act of immortality, is revealed upon critical examination to be a mechanism of narrative arrest. The artifact’s entry into the great institutional collection is, in essence, a declaration of its functional death.

The Archive Paradox and the Illusion of Immortality

The traditional museum was built upon a profound internal contradiction, functioning as a paradoxical archive of eternal presence, of profane immortality. Its purpose was to select specific objects, the artworks, and deliberately take them out of private and public use to immunize them against the destructive force of time. This institutional act of sequestering the object from the world of continuous function is the necessary prerequisite for granting it historical permanence. The object’s longevity is thus purchased at the cost of its present reality.

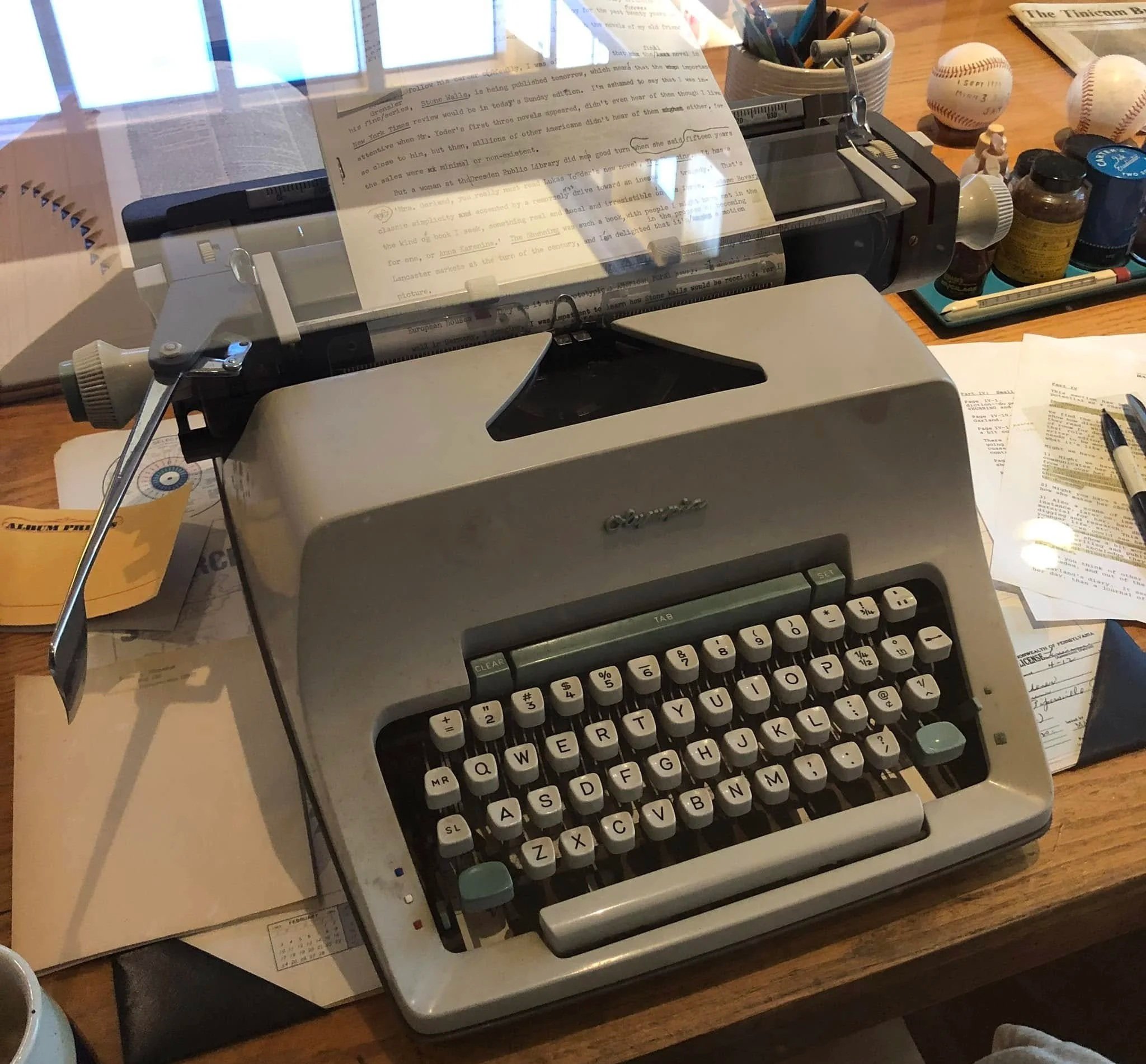

This image powerfully illustrates the modern archival impulse, in which the focus shifts from the physical artifact itself to the rigorous control of its epistemological record. The meticulous process of digitizing, capturing, and transforming a tangible object into data points on a screen shows how institutional authority shifts to managing the narrative, abstracted and ready for calculation. It's a crucial step that reduces the functional object to documentation. This file enables the kind of biopolitical control Foucault described, in which the object's dynamic history is suppressed in favor of a sanitized, quantifiable record.

This structural mandate led Boris Groys to the definitive observation that any object presented within the museum’s confines is automatically regarded as belonging to the past, as already dead. The archive exerts a powerful ontological veto over the artifact’s current life. Should an equivalent form be encountered outside the institutional walls, it is instantly diminished, perceived merely as "a dead copy of the dead". The museum, in this context, operates not as a sanctuary of continuous life but as a giant garbage can for history, housing objects formally declared obsolete or useless in "real life". For functional objects, such as those governed by the PLCFA principles, defined by continuous utility, this declaration of functional death upon institutional entry is a complete invalidation of their core purpose. The archive’s promise of immortality is exposed as a carefully orchestrated campaign of historical domestication.

The Shift from Presence to Documentation

The modern archival impulse has only intensified this death mandate by shifting institutional focus from the physical object itself to the control of its epistemological record. Contemporary museums increasingly resemble other historical and cultural archives, prioritizing the accumulation of art documentation that "does not necessarily appear before the public". This documentation is, by Groys's definition, "not art; it merely refers to art," making it clear that the physical object is often "absent and hidden".

This shift from object management to documentation control is the crucial moment where Groys’s archival critique aligns directly with Foucault’s analysis of power. The institutional authority is abandoning the complex reality of the material object in favor of controlling its narrative abstract. The functional object is reduced to documentation—a manageable file that serves as a passive referent to a reality that is functionally suppressed. This transformation, from a complex, dynamic material history into a sanitized, quantifiable file, is the essential archival prerequisite for biopolitical control.

Foucault demonstrated that biopolitics manages human populations by abstracting life into quantifiable data points—demographics, birthrates, statistics of health. Similarly, the institutional archive manages its population of cultural goods by demanding their functional obsolescence and subsequent reduction to administrative documentation. By controlling this record, the institution dictates the object's historical function, preemptively neutralizing any disruptive or radical political intent it may have held in its "live" state, thus acting according to the ideological function of art described by Groys. The greatest danger is not physical destruction, but the abstraction of the object into a statistical life unit, ready for institutional calculation.

It is fascinating to see an object like this typewriter, which was defined by its nonstop utility, transition into this state of perfect, enshrined preservation. The glass enclosure turns it into a powerful symbol, but the reality is this institutional embrace represents a profound contradiction: the guarantee of historical permanence often comes at the direct cost of its present day function and purpose. It makes you really think about what we prioritize when we decide to archive something, and why the objects we study must actively fight against becoming mere artifacts of the past.

Metaphysics of Resistance: Functional Endurance Against Temporal Partitions

The principle of Functional Endurance, far from being a simple material characteristic, is a necessary ontological assertion designed to resist the temporal fragmentation imposed by institutional history.

Endurantism and the Commitment to Presence

The mandate of Functional Endurance is an explicit, material commitment to the philosophical stance of Endurantism (or Endurance Theory). Endurantism posits that material objects are three-dimensional individuals that are "wholly present at every moment of their existence". The object endures through time, demanding that its identity be maintained through the continuous presence of its intrinsic properties. This metaphysical position stands in direct opposition to the institutional impulse, which operates through a framework closer to Perdurantism.

Perdurantism maintains that objects are four-dimensional “worms,” composed of successive, instantaneous "temporal parts". Under this view, the object’s identity is merely the sum of these segmented slices. The PLCFA object, by contrast, rejects the possibility of being reduced to a mere historical segment defined by a moment of pristine acquisition or obsolete function.

The PLCFA framework structurally resolves the metaphysical tension of how an object can change intrinsic properties yet remain the same. Functional Endurance is not passive material persistence; it is persistence through required utility. The necessary and sufficient conditions for the PLCFA object's identity over time are bound not just by material continuity but by a mandated functional performance. The artifact’s continuous identity is defined by the sustained realization of its intended purpose, making its persistence an active, deliberate project.

The Archival Embrace of Perdurantism

The traditional art archive inherently operates within a Perdurantist framework. When an institution acquires an artifact, it performs a temporal amputation, freezing a specific "temporal part"—often the moment of creation or highest perceived cultural value—and defining the object based on that stage. Perdurantism views the object as a mereological whole, encompassing its development and "final decay," and explains change simply as "the possession of different properties by different temporal parts of an object".

Institutional conservation and exhibition regimes are structurally designed to fix this preferred temporal slice. The goal is to prevent the object from generating new functional parts or histories that might complicate or disrupt the historical narrative defined by the institution. PLCFA’s mandate for functional use, however, is a continuous act of generating new, necessary, and often unpredictable temporal parts, thereby shattering the passive, defined historical segmentation demanded by the institutional history.

Kintsugi is the perfect material metaphor for functional endurance, demonstrating how the object maintains its identity not despite change, but because of it. Unlike the archival impulse that seeks to freeze a moment of pristine acquisition, this process shows that the object's history of use and subsequent repair is what generates necessary and unpredictable temporal parts, shattering the idea of passive historical segmentation. The resulting object is wholly present at every moment of its existence, embodying the Endurantist commitment and actively rejecting the Perdurantist view that the archive loves to enforce.

Furthermore, by forcing the discussion of identity over time onto an inanimate artifact, the PLCFA framework shifts the diachronic problem—the persistence of identity through time—from a question of personal or psychological continuity to one of functional continuity. The Custodian’s Contract is the legal tool used to enforce this new subject position. It serves as the legal mandate, ensuring the object’s intended function and integrity are continuously maintained and physically realized by the custodian. The defense is not merely material; it is a conceptual insistence that the object be recognized as a perpetually present, rather than historically segmented, entity.

The Apparatus of Security: Foucault, Biopower, and the Regulation of Duration

The threat posed by the institution is best understood through the lens of Foucault’s analysis of political control: Biopower and its instruments of governmentality. These mechanisms are deployed to manage the collective "population" of cultural goods, dictating which objects live, how long they live, and for whose benefit they expend their energy.

1. Biopolitics and the Efficiency of the Population (of Objects)

Modern power, or Biopower, is centered on the control and optimization of life itself, operating through strategies bent on "generating forces, making them grow, and ordering them". This management relies on governmentality—an expansive system of "institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, calculations, and tactics" that target a population’s efficiency.

In the realm of cultural administration, this political logic is perfectly replicated. Collections are managed as populations, and curatorial standards, acquisition rationales, and conservation decisions are instruments of governmentality. The biopolitical task is to maximize the collection’s overall vitality and minimize administrative risk. Foucault noted that biopolitics calculates the "overall health of the society writ large" through statistical recording of life metrics, such as birth and death rates and longevity.

In the institutional parallel, the administrative bodies—appraisal groups, conservation staff, and insurance providers—calculate the artifact’s projected longevity, its risk profile, and its rate of economic depreciation. This calculation determines its value as a political object within the institutional structure. The criteria for conservation or exhibition become apparatuses of security. Economic obsolescence, driven by market assessment and administrative costs, functions as the market’s biopolitical verdict on an object’s inefficiency, dictating whether it receives ongoing resources or is relegated to storage.

2. Thanatopolitics and the Institutional Right to Kill

The power to manage life necessarily encompasses its deadly reverse: thanatopolitics, the power to authorize death. Foucault observed that the modern state, when managing a population for its own sake, is "entitled to slaughter it, if necessary". This power justifies destruction through the vital end of protecting the overall population, where mass slaughter becomes justifiable through a logic of collective vitality.

When you talk about biopolitics managing the "overall health of the society writ large," this is what it looks like in a museum context. Collections are managed as populations, and this kind of high density storage is a structural manifestation of governmentality, a tactic to maximize the collection’s overall vitality and minimize administrative risk. When an object is relegated to this kind of unseen space, it's often the first step in thanatopolitics, the institutional "right to kill" its functional and narrative life because it’s been deemed inefficient or too costly to maintain. That entire section about calculated neglect being necessary for the long term health of the collection is why our framework, which breaks this dependency, is so critical, and you can only get the full picture by reading the entire study.

In the institutional context, this logic manifests as deaccessioning, calculated neglect, and planned functional obsolescence. When an object is deemed inefficient, irrelevant, or too costly to maintain, the institution exerts its thanatopolitical mandate—the "right to kill" its functional and narrative life. This death is rationalized as necessary for the long-term "health and well-being of the rest of the collection". This is an act of necropolitics, in which the artifact perishes administratively and is buried under the functional titles of enmity or neglect.

Crucially, biopower ensures that life is dependent on the work of power. An artifact under institutional control is only granted persistence (its life) contingent upon the institution’s disciplinary and administrative work (funding, conservation expertise, curatorial focus). The PLCFA framework is designed to break this dependency. By treating cultural institutions and luxury production as analogous sites of power where practices and strategies coalesce, involving power, discourse, and subjectivity, the functional object employs its framework to resist institutional subjectivization, refusing to become a passive, expiring commodity.

The Custodian’s Contract: Reclaiming the Object’s Narrative Sovereignty

The Custodian’s Contract is the strategic legal instrument that transforms the philosophical commitment of Functional Endurance into a codified, enforceable constraint on institutional power, reversing the traditional disciplinary dynamics.

1. The Precedent of Legal Resistance

The use of legally binding documents to assert the creator’s retained rights against the collector’s claims to the property has powerful precedent in conceptual art. The 1971 Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement, developed by Seth Siegelaub and Robert Projansky, sought to address inequities in the art world, specifically the creator's lack of control over their work and participation in its economy after they no longer own it.

Siegelaub’s contract established that legal constraints could effectively shift the relative power relationships concerning the artifact. It granted the artist specific, retained rights, including a resale royalty and, crucially, the right to veto the exhibition of their sold works. This mechanism provided the artist with negative control—the power to restrict use and profit. The Custodian’s Contract for the functional object moves beyond this limitation, imposing a series of positive mandates requiring continuous care and functional use. It is the legal scaffolding that enforces the object’s Endurantist ontology, compelling the continuation of its material identity over time.

2. The Contract as an Apparatus of Reverse Disciplinary Power

Foucault’s analysis of disciplinary power focused on subjects operating under the institutional gaze and permanent control. The Custodian’s Contract structurally inverts this dynamic, repurposing the apparatus of discipline against the institution itself.

The Contract transforms the act of ownership from a privilege of possession into a compulsory, sustained form of labor—the labor of maintenance and function. The legal mandates require the custodian to perform the ongoing work of life for the object, compelling the institution to adhere to the object's specific, rigorous standard of persistent identity.

This inversion is the essence of the institutional defense. If biopower rests on the capacity to take life or let live, the Contract fundamentally eliminates the institutional option of passive allowance or neglect. It mandates active, continual life maintenance, thereby transferring the agency of duration from the institution’s administrative capacity to the artifact’s self-determined, legally enforced framework. The custodian is thus repositioned as the disciplinary agent of the object, compelled by contract to fulfill the object’s requirement for function and persistence. The object, through its contract, weaponizes property law to enforce its own metaphysics.

This 1971 agreement, which asserted the artist's retained rights after a sale, is the critical legal ancestor of the Custodian’s Contract. While this early document focused on negative control, like the right to veto exhibition, our contract for the functional object takes the next crucial step, imposing positive mandates that compel continuous care and functional use. It structurally inverts the power dynamic of the institution, ensuring that ownership is transformed from a mere privilege of possession into a compulsory, sustained form of labor, making the custodian the disciplinary agent of the object. This is where property law meets metaphysics, and the artifact weaponizes the legal system to enforce its own persistence, a full explanation of which is available in the complete study.

Digital Provenance and the Unassailable Record

If the Custodian’s Contract enforces the object’s present and future conduct, Digital Provenance provides the ultimate epistemological defense, securing the object’s truthful biography against institutional vulnerability and narrative editing.

1. The Fragility of Centralized Archives

The functional object’s history is its primary claim to identity. If this history resides solely within traditional, centralized digital archives, it is highly susceptible to compromise. Digital records face inherent integrity issues; they are easily tampered with, compromised by improper migration processes, or rendered unreadable due to single-bit errors. Moreover, the constant evolution of information technology necessitates continuous, resource-intensive digital preservation activities—such as migration, emulation, and virtualization—to maintain records that are accurate, reliable, and authentic.

For the functional object, whose life cycle includes mandated repair and use, this inherent fragility means its biographical truth—the record of its care and continuous function—can be lost or deliberately edited by institutional actors driven by shifting political or resource demands. The traditional archive is vulnerable to both human malice and technological entropy.

2. The Blockchain as Counter-Archival Integrity

The necessity of ensuring trust and provenance—which require preserving the integrity (proving the record didn't change) and identity (proving the record is authentic)—is realized through distributed ledger technology.

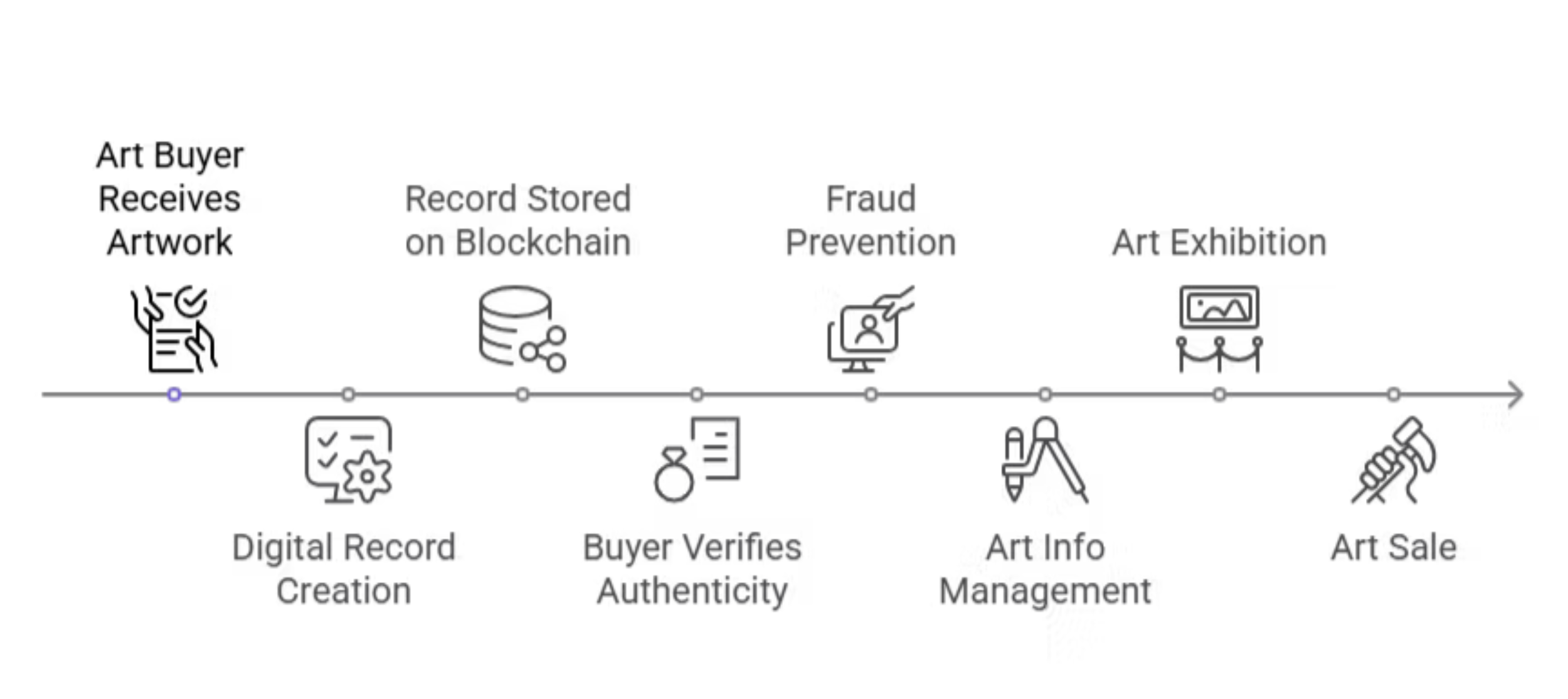

The permanent digital record, secured via blockchain-based provenance, acts as an immutable counter-archive. This is a direct challenge to the power/knowledge apparatus of the central institution. By securely registering every critical instance of the object's functional life—repairs, uses, condition reports, ownership transfers, and even contractual breaches—the system establishes a biographical record that is resistant to the institution’s traditional power to define historical truth and manage selective memory. This is the technological defense for the Material as Story principle established in From the Aura to the Simulacrum.

3. Reversing the Panopticon: Hermeneutic Surveillance

The deployment of Digital Provenance constitutes a strategic reversal of power dynamics described by Groys and Foucault. Groys observed that the use of digital platforms subjects the creative worker to the same or even greater degree of surveillance as the Foucauldian worker. However, this surveillance is more hermeneutic than disciplinary.

The functional object weaponizes this hermeneutic surveillance. Once the object’s record is made immutable and public, it exerts an irreversible gaze upon the custodian and the institution. The institution, traditionally the surveyor, becomes the party under continuous accountability for its adherence to the Custodian’s Contract.

This mandated transparency directly counters the biopolitical tactic of institutional forgetfulness—the administrative practice of losing older records or failing to migrate crucial data to maintain control over the narrative. The decentralized nature of Digital Provenance ensures that the administrative procedures—the calculations and tactics of governmentality—are themselves recorded and available for critical analysis. This ensures that any attempt by the institution to exert its thanatopolitical mandate (neglect, functional decommissioning) is permanently and publicly recorded as a failure of stewardship, thereby defending against the ultimate power move: erasure.

The deployment of Digital Provenance constitutes a strategic reversal of power dynamics against the institution. This timeline visualizes the system that secures every critical instance of the object's functional life, establishing a biographical record resistant to the power of selective memory and narrative editing. This technology ensures the institution, traditionally the surveyor, becomes the party under continuous accountability for its adherence to the Custodian’s Contract, which is the ultimate defense against the most powerful move of all: administrative erasure. You can see how this technological defense ensures narrative sovereignty by reading the full study.

The Meta-Archival Defense: Securing the Critique

The unified framework of Functional Endurance, the Custodian’s Contract, and Digital Provenance provides a complete structural defense against the biopolitics of the traditional archive. This defense must culminate in one final, necessary mandate to secure the entire project.

The apparatus is built upon three pillars: an ontological claim of persistence (Endurantism) that rejects archival death (Groys); a legal structure that compels life maintenance, reversing biopolitical dependency; and an epistemological tool that secures biographical truth against centralized control.

The Biopolitics of Assimilation and the Neutralization Threat

The greatest threat facing the functional object is not outright rejection, but assimilation. Institutions are masters of appropriation and ideological function. An institution may acquire the artifact, treat it merely as a highly conceptual piece of conceptual art, and then use its own power/knowledge structure to interpret the object as a historical curiosity—a reaction or an obsolete experiment.

This biopolitical neutralization allows the institution to retain its authority by absorbing the object’s material form while entirely neutralizing the critical content that defines the work. By treating the object only as a historically segmented artifact—a "dead copy of the dead"—the institution retains the power to declare the entire resistance project inert and contained.

The Archival Mandate: Demanding the Preservation of Critique

To prevent this biopolitical neutralization, the PLCFA framework must assert a non-negotiable strategic demand: that institutions archive not just the object and its associated provenance data, but the research framework itself—the full theoretical text, the Contract template, and the philosophical principles of the institutional defense. This strategic mandate is essential for Cultural Custodianship.

This final demand is a necessary act of narrative sovereignty. Archiving the framework forces the institution to acknowledge that the object’s continued existence is inextricably linked to a critical methodology designed specifically to expose and challenge the institution's biopolitical and archival logic. By demanding the preservation of the rules of the game alongside the artifact, the framework guarantees that the functional object’s presence in the archive functions as a permanent, active critique of the archival mandate itself, preventing the object from becoming a passive victim of institutional forgetfulness or biographical editing.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.