The New Avant-Garde: Deconstructing Status and Utility in the Age of Post-Luxury

Memory in Material: This Bokja tub chair, utilizing an intricate quilted patchwork of salvaged textiles, embodies the post-luxury ethos found in Beirut and beyond. It proves that the true value of an object is not its price but the cultural memory and resilience woven into its fabric, turning fragments into a cohesive, meaningful whole.

A World at an Inflection Point

Luxury, once thought eternal in its codes, has reached a state of exhaustion. For decades it seemed untouchable: a world of heritage maisons, rarefied ateliers, and objects designed to signal status through scarcity and price. But today, the sheen has dulled. Consumers who once aspired to logo-stamped handbags and limited-edition watches now question not only the cost but the very premise of what constitutes value.

We stand at a cultural threshold. The logos that once conferred belonging have become clichés of overexposure. The artisanal claims of heritage brands are too often undercut by scandals of hidden supply chains and exploited labor. The endless churn of collections, drops, and collabs has generated not awe, but fatigue. The very grammar of luxury—exclusivity, rarity, craftsmanship as image—has been hollowed out by scale and repetition.

Into this vacuum emerges a new movement: Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. The phrase was first coined by Christopher Banks to describe a set of practices he observed in his own work and across a widening field of designers, artists, and makers. It names something both artistic and philosophical: a turn away from luxury as commodity, and toward objects that matter because of their story, their resonance, their use. These works do not trade in status symbols, but in meaning.

Crucially, this is not a Western phenomenon alone. From Seoul to São Paulo, Cape Town to Kyoto, Beirut to Brooklyn, makers are dissolving the boundaries between art, design, and life. They are crafting objects that carry narrative, provoke thought, and demand engagement. They are not products for possession but vessels for connection.

In the age of post-luxury, the question is no longer what does it cost? but what does it mean? And in a world saturated with images and goods, meaning has become the rarest—and most desired—commodity of all.

“The next status symbol is not a logo but a story made tangible.”

Designed by the renowned Tokujin Yoshioka for the Swarovski Crystal Palace collection, the Venus chair is a truly unique creation. It's not carved, but rather grown, with crystals forming naturally around a delicate frame, making each piece a one-of-a-kind sculpture.

The Fall of Old-World Luxury

Growth Versus Rarity

For much of the 20th century, luxury’s alchemy was straightforward: limit production, raise prices carefully, preserve mystique. Scarcity was its engine, aura its fuel. But once global conglomerates entered the equation, these rules were first bent, then broken. Mass expansion, quarterly growth, and global scale became the imperatives.

Flagships multiplied on every major shopping street. Handbags once produced in limited ateliers were churned out in factory-like volumes, yet still marketed as “artisanal marvels.” Consumers began to feel the contradiction. The aura of rarity was impossible to sustain when the same bag was everywhere, its supposed scarcity an open secret.

The numbers tell the story. Between 2019 and 2023, nearly 80 percent of luxury’s growth came not from innovation or quality but from price hikes. Gucci, once unstoppable, reported revenue declines of nearly a quarter. Ted Baker collapsed outright. Paying more for less became the industry’s unsustainable mantra.

The paradox was fatal: a model built on rarity could not survive the logic of scale. By overreaching, the old luxury order hollowed out its own mystique.

The Scarcity Paradox Visualized: As luxury brands prioritized "Mass expansion, quarterly growth, and global scale," the aura of rarity became impossible to sustain. This graph illustrates how relentless expansion directly correlates with rising "Consumer Fatigue," ultimately hollowing out luxury's mystique as its supposed scarcity became an open secret.

From Aspiration to Authenticity

Equally destabilizing was the cultural pivot. For generations, luxury operated on aspiration: work hard, buy the branded good, signal arrival. A handbag was not simply leather and stitching—it was a symbol of having made it.

That logic no longer holds. A younger generation has rejected the idea that logos confer value. Normcore, once an ironic trend, has matured into a worldview: blending in is the new form of standing out. A plain, high-quality T-shirt now communicates more authenticity than a logo-stamped equivalent.

At the same time, “dupe culture” has flourished. Social media teems with tutorials on how to find affordable replicas virtually indistinguishable from the originals. What once created envy now breeds boredom. Scarcity has been replaced by omnipresence—and omnipresence breeds indifference.

Experiences have supplanted possessions as the ultimate signifiers of wealth. A silent retreat in Bhutan, a chef’s table in Copenhagen, or a bespoke wellness journey in Sri Lanka now carry more cachet than the latest handbag drop. Authenticity, intimacy, and personal resonance have overtaken acquisition as the markers of value.

“The new luxury is not aspiration but authenticity”

The Moral Collapse

The engine of disposability: This industrial scale of production highlights the system of ethical and material collapse that Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (P.L.C.F.A.) is built to resist, prioritizing permanence and intentionality over speed and volume.

Worse still, the ethical contradictions of old luxury have been laid bare. Investigations revealed undocumented workers producing “Made in Italy” garments under exploitative conditions. Loro Piana, Dior, Armani—all exposed for hypocrisy. What once signified provenance and integrity now risks being read as a mask for exploitation.

This betrayal has been devastating. Consumers who sought authenticity discovered stagecraft. “Heritage” proved to be branding. “Craftsmanship” was often illusion.

Against this backdrop, bespoke craft offers a striking counterpoint. In small ateliers and workshops, client and artisan work directly, with skill, time, and fair pay as non-negotiable. Here, authenticity is lived, not staged. Transparency is inherent, not performed.

The Corporate Response

Strategic Imperatives

Sensing the tremors, consultancies and conglomerates have begun drafting their prescriptions. McKinsey, Bain, and others issue familiar playbooks: reset strategy, restore product excellence, rethink client engagement, close the talent gap, future-proof portfolios. In practice, this often translates into the pursuit of “money-can’t-buy experiences,” diversification into hospitality, and attempts to tether products to “exclusive cultural moments.”

The playbook is not without merit. Experiences have become central to consumer desire, and there is indeed growth to be found in adjacent industries. But the underlying strategies feel like repackaged versions of old scarcity logics. An “exclusive dinner with a designer” is still just the promise of access. A luxury-branded hotel is often little more than a logo applied to architecture.

An exclusive drone light show at Art Basel Miami 2021 projects a giant Chanel N°5 bottle into the sky. This spectacle exemplifies how conglomerates attempt to restore aura by tethering products to “exclusive cultural moments” and “money-can’t-buy experiences,” treating the crisis as reputational rather than existential.

A Critical View

What is missing in these strategies is acknowledgment of the deeper cultural shift. They treat the crisis as reputational, not existential. They assume that aura can be restored by polishing brand image, when in fact the collapse is structural. Consumers are not rejecting luxury because the messaging failed; they are rejecting it because the product no longer corresponds to value.

The irony is striking: as brands double down on image, consumers demand substance. By clinging to performance, the industry misses the possibility of reinvention.

“Luxury’s problem is not its marketing, but its meaning.”

The collapse of value: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) embodies the intellectual groundwork for P.L.C.F.A. by questioning the status of the everyday object and proving that the idea, not the material, holds the artistic power.

A Global Genealogy of Post-Luxury

If we are to understand the present, we must understand the histories that make it possible. Too often, luxury narratives privilege a European and American lineage—Duchamp, LeWitt, Bauhaus—as if the conversation begins and ends there. But the reality is richer and more polyphonic. Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art does not arise from one root but from a constellation of traditions across continents.

Western Antecedents

In Europe and the United States, the intellectual groundwork was laid by conceptualism and modernist design. Sol LeWitt insisted that the idea itself could be art. Joseph Kosuth blurred distinctions between object, representation, and language with his One and Three Chairs. Duchamp’s readymades collapsed the distinction between the everyday and the artistic.

Meanwhile, Bauhaus insisted that function and beauty could be one, democratizing design without stripping it of dignity. A lamp, a chair, a ceramic bowl could carry as much gravitas as a canvas. Together, these traditions provided the intellectual scaffolding for a union of concept and function.

The idea as object: Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965) validates the P.L.C.F.A. principle of Conceptual Foundation by making the conceptual architecture of the object—not the physical object itself—the focus of the artwork.

Japan: The Mingei Movement

In Japan, the Mingei movement of the 1920s and 1930s, led by Yanagi Sōetsu, offered a parallel philosophy: the beauty of ordinary, anonymous craft. Everyday bowls, textiles, and tools were celebrated not for prestige but for honesty. The idea that an object could be valuable because it was humble, functional, and suffused with cultural meaning anticipates the ethos of post-luxury today.

The quiet authority of the functional object: Mingei ceramics, celebrated for their honesty and humility, laid the groundwork for the Post-Luxury ethos—proving that an object's value lies in cultural meaning and enduring use, not prestige.

India: Craft Modernism

In India, post-independence debates around modern design offered another foundation. Charles and Ray Eames’ famous India Report (1958) emphasized design rooted in local craft and material. From bamboo chairs to khadi textiles, Indian modernism was not about elitism but about dignity through making. This blending of modernity and tradition seeded a philosophy where material itself becomes cultural narrative.

Dignity through making: This functional chair, crafted from local materials like bamboo and cane, embodies Indian Craft Modernism—a philosophy where material itself becomes a powerful cultural narrative.

Africa: Functional Aesthetics

Across Africa, art and function have long been inseparable. Ghanaian kente weaving encodes history into cloth, its patterns carrying lineages of meaning. Yoruba bronze heads serve both as ritual objects and as repositories of ancestral memory. To treat these works as either “art” or “utility” misses the point—they were always both. Today, contemporary designers from Cape Town to Lagos draw directly from these legacies, embedding storytelling into everyday form.

Functional Aesthetics: Kente cloth exemplifies the tradition where art and utility are inseparable, its woven patterns carrying lineage and meaning—a core antecedent to P.L.C.F.A.'s emphasis on narrative and function.

The Middle East: Memory in Material

In Beirut, Damascus, and beyond, design has long been entwined with survival and identity. Post-war reconstruction gave rise to studios reusing debris—shattered stone, broken metal—as raw material. What emerged were not luxury goods but poignant memorials of resilience, objects where material is inseparable from narrative. This philosophy—where the scar is also the ornament—directly prefigures the post-luxury ethos.

Memory in Material: Cynthia el Frenn and Yara Chaker’s memorial object, created from Beirut explosion debris, embodies the philosophy where the material’s scar is inseparable from its powerful, enduring narrative of resilience.

Indigenous Philosophies

Among Indigenous cultures globally, utility and sacredness have never been divided. A woven basket in the Pacific Northwest, an Aboriginal painting in Australia, or a Māori carved meeting house panel—all carry use and spiritual story simultaneously. These traditions remind us that “post-luxury” is not entirely new. It is, in some sense, a return: a rejoining of what industrial modernity divided.

Utility and Sacredness Rejoined: Indigenous traditions, exemplified by this Klickitat woven basket, remind us that P.L.C.F.A. is a return—a rejoining of function and spiritual narrative that industrial modernity wrongly divided.

“Post-luxury does not begin in Paris or Milan. It begins wherever function and meaning have always been one.”

Defining Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art

The phrase Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art was coined by Christopher Banks not as a claim of authorship but as a way to name what he observed across his own practice and others: a convergence of art, design, and philosophy in which objects are both useful and conceptual, material and narrative.

This is not a style or a trend. It is a shift in cultural logic.

The convergence: The Indlovu Wallet, functional object and philosophical vessel by Christopher Banks, illustrates the fusion of art, design, and philosophy in which objects are both useful and conceptual.

Core Principles of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art

Utility as Essential Foundation: Function is not secondary decoration but is essential to the work's existence. The practical purpose (sitting, holding, gathering) becomes the primary canvas for the conceptual statement.

Narrative Over Material: Value is shifted away from the preciousness of materials to the depth of narrative, symbolism, and craftsmanship. The material's story, resonance, or critique is the source of prestige.

Resistance to Replication: Works prioritize permanence and stand as irreplicable embodiments of thought and craft, directly resisting disposability and mass-production.

Dialogue Through Object: Each piece acts as a philosophical vessel, communicating an idea, belief, or cultural critique, often interrogating contemporary notions of consumption and identity.

Authenticity Through Intentionality: The object's worth is rooted in the intentionality and transparency of its making, moving beyond the consumption-driven model of exclusivity and the spectacle of luxury branding.

Beyond Luxury

The point is not to create another elite category of goods, but to reframe value itself. Post-luxury objects may be rare, but they are not about exclusion. They are about connection—between maker and client, between material and memory, between function and philosophy.

Manifestations and Case Studies

If the genealogy gave us the roots, the case studies show us the flowering. Across continents, artists, designers, and makers are embodying the post-luxury ethos. Some come from the art world, others from design, others from craft. What unites them is not style but philosophy: a refusal to separate use from meaning, or material from story.

Artists as Commentators

In Chicago, Dan Peterman’s recycled plastic tables invite diners to sit with the reality of waste. Each meal becomes an act of reflection on ecological cycles, turning a simple surface into a site of critique. In New York, Cady Noland constructs aggressive arrangements of beer cans, scaffolding, and metal fencing, forcing viewers to confront American violence and media spectacle. These are not inert works of art but charged functional objects, their “use” inseparable from their message.

Functional critique: Dan Peterman’s recycled plastic tables exemplify P.L.C.F.A. by turning the simple functional act of sitting into a site for reflection on ecological cycles, proving that utility is inseparable from message.

The Co-option Game

Luxury conglomerates have attempted to tap into this energy. Louis Vuitton’s collaborations with Takashi Murakami or Jeff Koons, Dior’s limited-edition works with contemporary artists—all are efforts to borrow art’s aura. But these collaborations often underscore the fragility of the traditional model. They reveal that products alone no longer suffice; meaning has to be imported.

In contrast, post-luxury objects don’t borrow narrative, they are narrative. Their aura is not purchased from artists but emerges from intent and material.

Borrowed Aura and Spectacle: By using classical paintings, this Louis Vuitton x Jeff Koons collaboration underscores the fragility of the traditional luxury model—meaning must be imported from high art and history, rather than emerging from the product's inherent intent and material.

“The difference between branding and meaning is the difference between borrowing and being.”

Transparency as Prestige

Post-luxury elevates transparency to the status of prestige. Unlike blockchain “curated stories” or staged artisan campaigns, real provenance is unembellished and exacting. Where was this wood cut? Who tanned this leather? Which dyes stained this silk? These details become signatures more powerful than any logo.

Christopher Banks and Objects of Affection Collection

The Benchmark: Christopher Banks’s The Garden of Art perfectly embodies the P.L.C.F.A. ethos: a ritualistic object inseparable from its personal narrative, proving that true value arises when memory and form become one.

Christopher Banks’s Objects of Affection Collection is a paradigmatic expression of post-luxury philosophy. Each piece is conceived as a “One Original,” collapsing the line between function and concept. Banks selects materials not for opulence but for resonance—sometimes with himself, sometimes with the client—ensuring that each object embodies a living narrative rather than a static luxury posture.

These are not commodities. They are gestures of permanence, devotion, and story. A chair might hold timber that echoes a family history. A table might be constructed of stone that speaks to a personal geography.

One celebrated example, The Garden of Art: A Woven Memoir in Silk, distilled this ethos in a singular gesture. Conceived not for a client but as a gift to his mother, it became the benchmark for the entire practice. A silk carré, hand-rolled on Savile Row, dyed in Como, and painted in Verona, it embodied the fusion of memory, material, and mastery. The scarf was not simply wearable but ritualistic: its presentation demanded that the narrative be absorbed before the object was unveiled. The result was an object inseparable from story—devotion made manifest.

Yet the significance of Objects of Affection lies not in any one artifact but in its philosophy. True value, Banks insists, arises when narrative and form become inseparable, when an object exists not as a marker of status but as a vessel of memory.

Robert Ebendorf: A Foundational Parallel

Narrative Over Material: Robert Ebendorf’s use of mixed media and found objects in this charm necklace subverts traditional luxury, proving that the artistic and conceptual value lies entirely in the story and arrangement of commonplace materials.

Robert Ebendorf, through his project Objects of Affection (a separate body of work, though deeply aligned in philosophy), offers a parallel but equally potent vision. His conviction is that jewellery must be more than ornament; it must be narrative, archive, conversation. To that end, he juxtaposes the precious with the ordinary—gold and silver paired with photographs, plastics, or scraps of paper.

The result is jewellery as cultural archaeology. Each piece is a layered record of life, carrying fragments of memory and ephemera. Value here is not dictated by carats but by connection. Ebendorf reminds us that beauty is found in dialogue between the elevated and the humble.

In this commitment, his work establishes a historical precedent for the principles that later crystallized in Christopher Banks's Objects of Affection Collection. Both insist that the true luxury is story, embedded and enduring, proving that the Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art ethos is a universal return to intentionality and inherent meaning, not a singular invention.

Global Voices

The power of post-luxury lies in its polyphonic chorus. Around the world, makers articulate the philosophy in different keys, but with shared conviction.

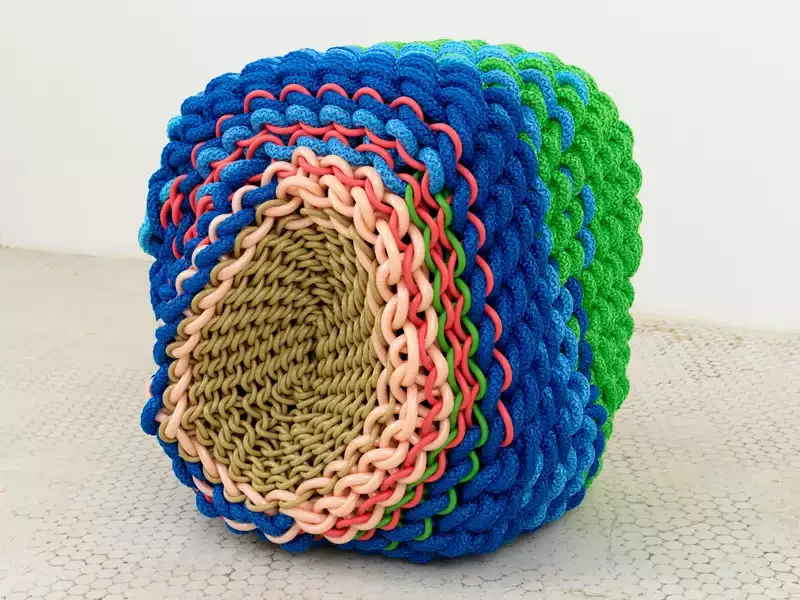

Seoul: Designers like Kwangho Lee use traditional weaving techniques to create monumental furniture from synthetic rope. The result is both futuristic and ancestral, collapsing past and present.

Mexico City: Collectives like Studio IMA curate objects from ceramics to lighting, all rooted in Mexico’s craft traditions but reframed in contemporary forms. These are not decorative imports but cultural continuities.

Cape Town: Southern Guild champions designers like Andile Dyalvane, whose clay vessels are embedded with Xhosa spirituality and narrative. These are works to be lived with, touched daily, yet also carried with ancestral depth.

São Paulo: Designers rework tropical hardwoods into pieces that critique deforestation, turning beauty into protest.

Beirut: Post-war ateliers like Bokja reclaim fragments of textile and furniture, weaving them into collaged objects that bear witness to cultural resilience.

Tokyo: Tokujin Yoshioka’s crystal chairs literalize light itself as a material, reminding us that function and poetry need not be apart.

Indigenous Americas: From Navajo weavers to Amazonian basket makers, utility and sacredness remain entwined. These practices remind us that post-luxury is not wholly new but often a return to wisdom industrial modernity forgot.

Collapsing Past and Present: Kwangho Lee's functional furniture, woven from synthetic rope using traditional techniques, is both futuristic and ancestral, embodying the P.L.C.F.A. principle of Dialogue Through Object.

A New Economy of Meaning

The decline of old-world luxury was inevitable. Scale eroded scarcity. Opacity destroyed trust. Logos lost their power. The gilded façades of Avenue Montaigne and Fifth Avenue no longer signal permanence but exhaustion. What remains is not collapse but transformation—the recognition that the cultural contract luxury once upheld has been broken, and something new has emerged in its place.

Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art does not attempt to repair the old order. It refuses the nostalgic dream of reviving aura through limited editions or “money-can’t-buy” experiences. Instead, it reframes value entirely. It proposes a different equation: not possession, but resonance; not display, but dialogue; not opulence, but permanence.

The Gilded Façade: This hyper-stylized Hermès ad campaign symbolizes the reliance on pure spectacle and fantasy in traditional luxury, underscoring the exhaustion and fragility of a model detached from material substance and intentionality.

The Logic of Resonance

In this new economy, value is measured by resonance. Does the object connect? Does it carry story? Does it embed memory? These are the questions that matter more than price or logo. A table that critiques waste, a necklace that preserves memory, a chair that holds history—these are not simply objects, but sites of encounter between the individual and the collective, the material and the symbolic.

Resonance cannot be scaled infinitely. That is precisely its power. Unlike logos, which can be stamped a million times, narrative resists duplication. Each post-luxury object is singular, not because it is scarce by design, but because its meaning is specific, intimate, unrepeatable.

Permanence and Devotion

At its core, post-luxury insists that objects are not transactions but devotions. They are not meant to be flipped, resold, or discarded when fashion shifts. They are designed to be stewarded, lived with, and eventually passed down—not as commodities but as carriers of meaning.

This marks a radical departure from the culture of novelty that has defined luxury for decades. Instead of the endless churn of seasonal drops, the movement calls for permanence. Instead of consumption, it calls for care. Instead of status, it calls for story.

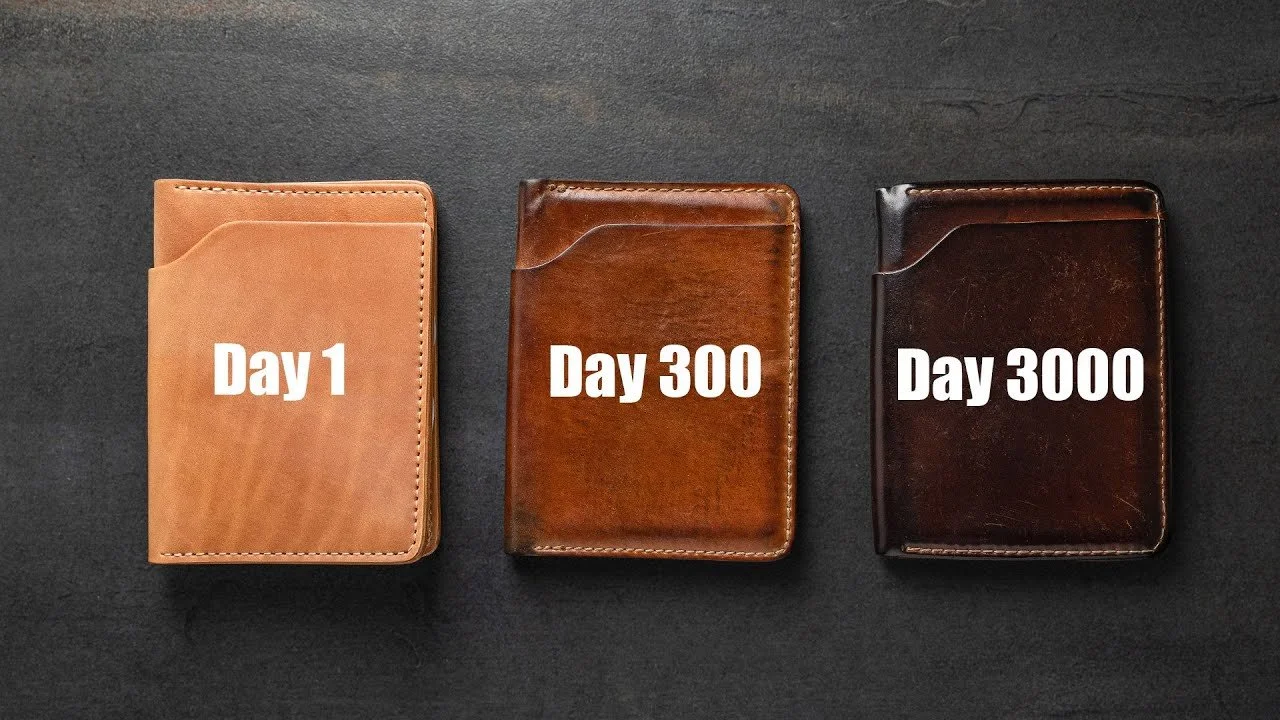

Patina as Narrative: This timeline of a Horween Raw Shell Cordovan wallet proves that value is created through stewardship and care over time—not novelty. The object is a companion, designed for permanence, not disposal.

From Commodity to Companion

A handbag in the old model is an accessory. In the new model, it is a companion. A chair is not furniture but a place-memory. Jewellery is not adornment but archaeology. These shifts reorient the entire category of object. No longer silent, they become interlocutors in daily life—holding, reminding, whispering.

“In post-luxury, objects do not decorate a life—they accompany it.”

The Global Horizon

What makes this movement urgent is that it is not bound to Europe or America. It is not Milan dictating taste or New York declaring value. It is a global chorus—Tokyo, Lagos, São Paulo, Beirut, Seoul, Oaxaca, Auckland—each contributing its own articulation.

Post-luxury is not the invention of one culture but the convergence of many. It is not a trend to be owned but a philosophy to be shared. In this sense, it is both contemporary and timeless: contemporary in its articulation, timeless in its recognition that objects have always been vessels of meaning.

Toward a Manifesto

What, then, is the call of post-luxury? It is not to buy, but to see differently. Not to consume, but to engage. Not to seek prestige, but to cultivate presence.

Its objects are not items of luxury as we once knew it. They are objects of affection, archaeology, and devotion. They are not silent but storied. They are not symbols of status but companions of meaning.

The movement does not ask us to abandon beauty, but to deepen it. It does not reject craft, but insists that craft serve more than commerce. It does not abolish luxury, but redefines it—no longer as the rarefied privilege of the few, but as the resonance available to all who engage with material, story, and care.

Luxury’s Future Is Meaning Itself

Luxury’s future is not luxury as we knew it. The logo has lost its spell, the boutique its aura, the unboxing its thrill. What remains is something quieter, deeper, more enduring.

Luxury’s future is not scarcity, but story.

It is not novelty, but permanence.

It is not aspiration, but resonance.

In the age of post-luxury, the most valuable possession is not a thing but a meaning made tangible.

Objects that matter.

Objects that endure.

Objects that live.

And perhaps, in this quiet transformation, we rediscover something we had forgotten: that true luxury was never about what we owned. It was about what owned us—the stories, the memories, the devotions—that make life not only adorned, but alive.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.