The Aesthetics of Endurance: Byung-Chul Han and the Rise of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art

The Weight of the Weightless

We live amidst a profound paradox: a world saturated with objects, yet starved of meaning. The relentless currents of late-stage capitalism have delivered an unprecedented proliferation of goods, each designed for frictionless acquisition and swift obsolescence. This material landscape, from the seamless glass of a smartphone to the endless scroll of a social media feed, promises a life of effortless positivity but delivers a pervasive sense of exhaustion and alienation. We possess more than any generation in history, yet our possessions seem to possess us less, leaving a silent void where tangible connection once resided.

No contemporary thinker has diagnosed this cultural malaise with more precision and urgency than the Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han. His work provides the essential vocabulary for understanding the pathologies of our time, from the tyranny of digital transparency to the quiet violence of self-exploitation. Han’s analysis, however, is not merely a diagnosis; it is an implicit call for an antidote, for a form of resistance against the weightless, frictionless, and ultimately meaningless aesthetic that defines our era.

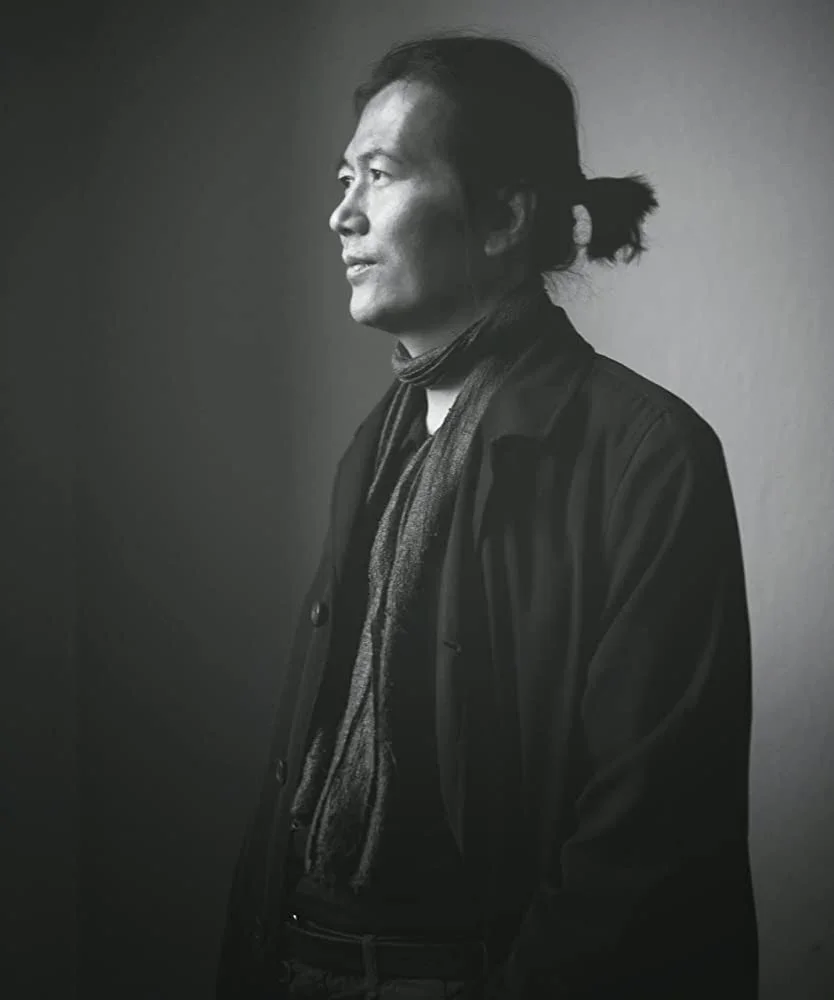

The Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han. His diagnosis of the 'burnout society' provides the essential vocabulary for understanding the pathologies of our time.

This study argues that the antidote is emerging not from a manifesto, but from the material world itself, in a new category of objects defined as Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA). These are objects designed with both function and philosophy at their core, where value is derived from narrative and permanence, not price or brand status. In their deliberate resistance to disposability, PLCFA objects serve as interlocutors in daily life, providing a tangible anchor of meaning. Han’s philosophy provides the critical framework for understanding why these objects are not merely an aesthetic preference, but a necessary form of cultural therapy—a profound and tangible commitment to endurance in an age of the ephemeral.

The Tyranny of the Smooth: Han's Critique of a Frictionless World

To comprehend the necessity of PLCFA, one must first grasp the condition it seeks to remedy. At the heart of Han’s critique is the concept of “smoothness”, which he identifies as the dominant aesthetic of the 21st century. This is not a simple matter of design preference but a pervasive social imperative with deep psychological consequences, an aesthetic that reflects and reinforces a culture of relentless, exhausting positivity.

The Aesthetic of the Same

Smoothness is the signature of the digital age, connecting the polished sculptures of Jeff Koons, the seamless interface of the iPhone, and the digitally airbrushed perfection of an influencer’s photograph. Its defining characteristic is the total absence of resistance, negativity, friction, or texture. The smooth object, Han argues, “does not injure. Nor does it offer any resistance. It is looking for a Like”. It is the physical manifestation of a society that systematically eliminates anything deemed difficult, complex, or “other,” demanding only immediate, frictionless affirmation.

This aesthetic creates a shallow, closed loop of interaction. The perfectly polished surface of a device or a Koons sculpture does not present an external world with its own history and resistance; it acts as a mirror, reflecting only the viewer’s own gaze. Han terms this an “autoerotic” relationship, where we encounter only ourselves, never the alterity of the other. This constant self-referentiality prevents the possibility of a genuine, transformative experience, locking us into a comfortable but empty echo chamber of the Same.

Jeff Koons' 'Balloon Dog' epitomizes the "smooth" aesthetic: polished, frictionless, and designed for immediate, unchallenging affirmation.

Deleting the 'Against'

The ultimate consequence of smoothness is the foreclosure of deep experience. Han posits that true perception requires a vulnerability to what he calls “injury”—the shock, disturbance, or resistance that arises from an encounter with something genuinely different from oneself. A smooth world, by its very nature, “deletes its Against” and thus makes this profound form of engagement impossible. Beauty, which for the ancients contained the sublime and the terrible, has been sanitized, stripped of its negativity, and rendered into a mere commodity to be consumed without thought. The smooth object does not invite contemplation; it demands consumption and elicits only a fleeting “Wow”.

This aesthetic is more than just a symptom of our cultural condition; it is the essential interface that enables and accelerates the pathologies of the burnout society. Han’s achievement-subject is driven by the imperative to perform and optimize, a state that requires a shallow, multitasking mode of awareness he calls “hyperattention”. The smooth, frictionless design of our digital tools—the infinite scroll, the seamless transition between apps—is engineered to maintain this state of continuous partial attention, preventing the “negative” states of deep focus or profound boredom that Han identifies as crucial for mental relaxation and genuine creativity. In this way, the aesthetic of smoothness serves as the lubricant for the engine of self-exploitation, facilitating the very psychological conditions that lead to cultural exhaustion.

The Haptic Resistance: PLCFA and the Re-enchantment of the Material

If smoothness is the aesthetic of a culture in crisis, then PLCFA emerges as its direct antithesis. It is an aesthetic of friction, texture, and depth that actively resists the logic of seamless consumption. Through their material and conceptual properties, these objects reintroduce a necessary and therapeutic difficulty into our lives, re-enchanting a material world that has been stripped of its magic.

The Narrative Depth of the 'Un-Smooth'

The aesthetic of PLCFA is intentionally “un-smooth.” These objects are defined by what the smooth aesthetic eliminates: texture that invites touch, asymmetry that challenges perception, visible signs of their making, and material histories that offer resistance. They are objects that must be contended with, not merely consumed.

The core value of a PLCFA object lies not in its material composition but in its narrative depth. This is the principle that an object’s story—the philosophy of its creator, the ethical provenance of its materials, the history embedded in its form—is its most precious quality, far surpassing market price or brand status. This stands in direct opposition to the characterless, ahistorical nature of smooth, mass-produced goods, which Han argues are stripped of duration and solidity to accelerate consumption.

Case Study in Asymmetry and Imperfection: The Wabi-Sabi Tradition

A profound historical antecedent to the PLCFA ethos can be found in the Japanese philosophy of Wabi-Sabi. More than a mere aesthetic, Wabi-Sabi is a worldview centered on the acceptance and appreciation of imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. It finds a quiet, austere beauty in the very “flaws” that the culture of smoothness seeks to erase: roughness, asymmetry, cracks, and the humble patina of age.

A ceramic tea bowl in the Wabi-Sabi tradition is valued not despite its imperfections, but precisely because of them. An uneven glaze or a slightly distorted form testifies to the hand of its maker and the unpredictable forces of the kiln, celebrating the collaboration between human intention and natural process. The philosophy teaches one to see a chipped vase or a cracked bowl as meaningful and beautiful, not in spite of the flaw, but because of it, as the imperfection offers a space for reflection on the transient nature of existence.

In the Wabi-Sabi tradition, a ceramic tea bowl's uneven glaze and distorted form are not flaws, but testaments to its unique history and the beauty of imperfection.

This principle is perhaps most powerfully embodied in the art of kintsugi, the practice of repairing broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold. Instead of attempting to hide the damage, kintsugi highlights the lines of fracture, celebrating the object’s history of breakage and repair as a central and beautiful part of its identity. It is a radical act of preservation and a direct refutation of the logic of disposability that governs our smooth, modern world.

The art of kintsugi, or "golden joinery," radically refutes disposability by highlighting an object's history of breakage and repair as a central part of its beauty.

Case Study in Material Alchemy: The Work of Robert Ebendorf

A contemporary master of the PLCFA ethos is the American studio jeweler Robert Ebendorf. His lifelong practice serves as a case study in the power of the “un-smooth,” built on the alchemical transformation of discarded and overlooked materials into philosophical objects of profound worth. Ebendorf is a self-proclaimed “gleaner,” finding his materials in the detritus of modern life—a rusted bottle cap, a forgotten tintype photograph, a crab claw washed ashore.

His work demands a haptic, or touch-based, engagement. The masterful juxtaposition of these found, non-precious materials with traditional goldsmithing techniques creates a conceptual and textural friction. This forces the viewer to slow down, to contemplate the arbitrary nature of value, and to question what it is that makes an object precious. This is the essence of the un-smooth experience: an encounter that challenges, rather than merely pleases. As detailed in our study, his work embodies a form of de-branding as authenticity, where irreplicable craftsmanship and narrative depth create a new framework for luxury.

This radical re-evaluation of material worth is a cornerstone of the post-luxury movement, which deconstructs the exhausted grammar of traditional status symbols. As we have explored in that study, the shift is away from value defined by price and toward value defined by resonance and meaning. Ebendorf’s practice is a perfect embodiment of this new paradigm.

A work by studio jeweler Robert Ebendorf, who alchemizes discarded materials—like this crab claw—into philosophical objects, forcing a haptic, contemplative engagement with the nature of value.

From Smooth Consumption to Cultural Exhaustion: The Burnout Society

The aesthetic of smoothness and the economic logic of hyper-consumerism are not benign forces; they are deeply implicated in the socio-psychological condition that Han terms the “burnout society”. This is a society defined by an excess of positivity, where pathologies arise not from external repression but from an internal, self-generated pressure to perform.

The Achievement-Subject as Ultimate Consumer

Han charts a historical shift from Michel Foucault’s “disciplinary society,” governed by external prohibitions and the negativity of “should not,” to our contemporary “achievement society,” driven by the internal imperative of “can”. In this new paradigm, the individual becomes an “achievement-subject,” freely choosing to exploit themselves in an endless, anxious pursuit of optimization and productivity. The exploiter and the exploited become one and the same, making this system of auto-exploitation incredibly efficient and almost impossible to resist.

This constant pressure to perform and “produce oneself” transforms the act of consumption into a key ritual. We no longer consume primarily to satisfy needs, but to perform an identity, to brand ourselves as successful, authentic, and relevant. The frictionless cycle of acquiring and discarding the latest goods becomes a way of demonstrating one’s ability to keep pace with the accelerating demands of the achievement society.

Hyperattention and the Disposable Trend Cycle

This culture of performance is sustained by the state of “hyperattention” that Han describes—a shallow, scattered mode of focus that jumps restlessly from one stimulus to the next, incapable of deep contemplation. The logic of the modern consumer market, particularly in sectors like fast fashion, is perfectly calibrated to fuel this state. The relentless acceleration of trend cycles creates an endless stream of novelties that demand our fleeting attention, preventing the formation of deep, lasting bonds with our material possessions.

As Han notes, “Consumption and duration exclude each other”. An object designed to be obsolete in a single season cannot possibly accrue the narrative depth, patina, or character required for a meaningful, long-term relationship. This logic of disposability is a primary driver of cultural exhaustion. The constant need to update, upgrade, and replace contributes to the psychic fatigue of the achievement-subject, who is trapped on a treadmill of performative consumption. This is the paradox at the heart of the modern luxury industry, a system that, as detailed in that study, has sacrificed creativity and endurance at the altar of unsustainable acceleration.

The logic of disposability, fueled by hyperattention and accelerated trend cycles, results in cultural and material exhaustion. Objects designed for obsolescence drive this cycle of performative consumption, sacrificing endurance for fleeting novelty.

The contrast between these two aesthetic worlds is stark. The core principle of Han’s smoothness is an unrelenting positivity that eliminates all negativity, whereas the un-smooth aesthetic of PLCFA finds value in the acceptance of imperfection and what Han might term “productive negativity.” This philosophical difference manifests physically: the smooth object is frictionless, polished, and seamless, while a PLCFA object is defined by its texture, asymmetry, and patina. Consequently, the interaction with each is fundamentally different. Smoothness encourages passive consumption and an “autoerotic” gaze where the viewer only encounters a reflection of themselves, eliciting a simple “Like.” PLCFA, however, demands active contemplation and an encounter with the “other”—a dialogue with the object’s history and materiality.

Their temporalities and sources of value are also opposed. The smooth object exists in a hyper-present, designed for disposability and fleeting novelty, its value derived from brand and price. The PLCFA object is an emblem of endurance and permanence, its value rooted in its narrative, craft, and authentic material history. The psychological effects diverge accordingly. The world of smoothness fosters the hyperattention Han describes—a state of distraction and exhaustion that fuels the burnout society. Conversely, the difficulty and depth of a PLCFA object encourage the deep focus of the vita contemplativa, providing a sense of grounding. The archetypes are clear: on one side, the iPhone or a Jeff Koons sculpture; on the other, a Wabi-Sabi tea bowl or a Robert Ebendorf brooch, each embodying a radically different relationship to the material world.

Cultural Therapy: PLCFA as an Act of Endurance

Positioning PLCFA within Han’s philosophical framework reveals that it is far more than a category of objects. It is a practice, a form of cultural therapy that offers a tangible means of resisting the pathologies of the burnout society. To choose to live with a PLCFA object is to make a radical commitment to slowness, difficulty, and endurance.

The Object as Interlocutor: A Commitment to Slowness

PLCFA objects function as “interlocutors” in our daily lives. Their material complexity and conceptual weight demand the very vita contemplativa—the contemplative life—that Han argues has been obliterated by the hyperactivity of the achievement society. One cannot simply “Like” an Ebendorf brooch or passively consume a Wabi-Sabi tea bowl; one must engage with it, question its origins, feel its texture, and spend time in its presence.

The inherent “difficulty” of a PLCFA object—its refusal to be immediately understood or categorized—is its primary therapeutic value. It acts as a form of resistance training for the hyper-attentive mind, a “pedagogy of seeing” that re-cultivates our capacity for deep, slow, and meaningful focus. It forces a pause in the relentless flow of information and stimulation, creating a space for the quiet contemplation that is the only true antidote to burnout.

Stewardship Over Ownership: The Radical Act of Care

The acquisition of a PLCFA object is an act that transcends mere consumption; it is the beginning of a long-term relationship. This reframes the dynamic from one of ownership to one of stewardship. To care for such an object—to understand its story, preserve its materials, and accept its evolution over time—is a radical act of resistance against the logic of disposability.

This commitment to care stands in direct opposition to the logic of self-exploitation, which views everything, including the self, as a project to be optimized, performed, and ultimately discarded for a newer version. By choosing to live with an object of endurance, one implicitly cultivates a form of personal endurance. Han argues that the culture of consumption erodes “character,” which he defines by its “duration, solidity and permanence”. The ideal consumer is characterless, able to flow seamlessly from one trend to the next. PLCFA objects, by their very nature, are imbued with character. To engage with them is to re-engage with the concept of character itself, re-inscribing a sense of permanence into a life from which it has been systematically erased.

The Aesthetics of Endurance

Ultimately, PLCFA represents a profound philosophical choice: a commitment to endurance in an age defined by the ephemeral. It is an aesthetics of endurance. By embracing objects that possess narrative, imperfection, and resistance, we are, in Han’s terms, “saving the other”—making space in our lives for things that are not merely reflections of our own ego but are challenging, independent entities with their own stories to tell. This act of saving the other is the first step toward saving ourselves from the narcissistic, autoerotic loop of the smooth.

To choose a PLCFA object is to choose contemplation over calculation, permanence over performance, and meaning over the silent, polished void of the Same. It is, in the most literal and necessary sense, to grasp something real in a world that has become dangerously weightless.

The "Aesthetics of Endurance" is an act of stewardship and a commitment to slowness. The haptic, contemplative work of the artisan is the physical antidote to the weightless, disposable culture of the "smooth," re-inscribing meaning and permanence into the material world.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.