The Simulacrum of Luxury: A Guide to Jean Baudrillard's Critique of Consumer Society

The frictionless, reflective surfaces of modern luxury spaces create an unsettling 'hall of mirrors,' where the distinction between the real and its dazzling representation begins to dissolve.

In the luminous, frictionless world of contemporary luxury, a persistent and unsettling feeling of emptiness has taken hold. We are surrounded by objects of immense price but questionable value, by brands that trade in heritage but produce for the moment, and by a relentless cycle of desire manufactured on digital screens. This is a world of perfect surfaces and hollow cores. To navigate this landscape—to understand how luxury became a hall of mirrors reflecting only itself—we require a guide, a cartographer of the unreal. That guide is the French philosopher and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard. His work provides the definitive framework for diagnosing the terminal condition of a consumer society saturated by images and signs.

This article advances a two-part thesis. First, it argues that Jean Baudrillard's philosophy, particularly his concepts of sign value, simulacra and simulation, and hyperreality, offers the most potent critique of modern luxury, revealing it as a system of signs entirely detached from any grounding in material reality. Second, it proposes that a potent form of resistance to this hyperreal consumerism has emerged in the form of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA). This movement, embodied by practices like the Objects of Affection Collection, counters the logic of the simulacrum by reintroducing authentic function, narrative, permanence, and a form of value based on what Baudrillard called "Symbolic Exchange"—a value that cannot be commodified or simulated. In a world of floating signs, PLCFA offers a tangible anchor of meaning.

Who Was Jean Baudrillard? A Brief Intellectual Portrait

Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007), the influential French philosopher and cultural theorist, whose work provides a definitive critique of consumer society and the hyperreal.

Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) was a French sociologist, philosopher, and cultural critic whose intellectual trajectory perfectly mirrored the societal shifts he so brilliantly diagnosed. He began his academic life not as a philosopher but as a Germanist, translating the works of figures like Bertolt Brecht and Karl Marx. This early grounding in language and political economy shaped his initial forays into sociology, which he pursued under the tutelage of influential thinkers such as Henri Lefebvre and Roland Barthes. His first major works, The System of Objects (1968) and The Consumer Society (1970), were still loosely tethered to a Marxist framework, seeking to decode the system of objects and their meanings in the burgeoning consumer culture of post-war France.

However, Baudrillard soon grew dissatisfied with the limitations of Marxist analysis. He concluded that Marx's focus on the mode of production was becoming obsolete in a world increasingly dominated by the mode of consumption and the logic of signs. His decisive break came with For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1972), in which he argued that the semiological (sign-based) system of advertising and media had superseded the material system of production as the organizing principle of late capitalism.

This theoretical pivot launched the most radical and influential phase of his career. Dubbed the "high priest of postmodernism," Baudrillard turned his attention to the ways in which media and technology were fundamentally altering our perception of the world. He developed his signature concepts of simulacra and simulation to describe a new state of existence where the distinction between the real and its representation had collapsed. For Baudrillard, contemporary society was no longer a spectacle to be watched, but a simulation to be inhabited. He saw this condition most purely in the United States, which he described in his travelogue America (1986) as a glittering, cultureless void—the world's first and most perfect hyperreality, a "desert of the real". His intellectual journey, from analyzing the production of things to the simulation of reality, was not merely a personal evolution; it was a reflection of late capitalism's own structural transformation from an industrial economy to an information economy. Baudrillard did not just observe this change; his thinking evolved with it, making him a native guide, not a foreign tourist, to the hyperreal world we now inhabit.

The Four Stages of the Sign: From Value to the Void

To understand Baudrillard's critique, one must first grasp his theory of value, which charts the progressive abstraction of meaning from the tangible world to a realm of pure simulation. Building on Marx's distinction between use-value and exchange-value, Baudrillard introduced a third term, sign-value, before identifying a fourth, terminal stage where value implodes entirely. This progression is not merely a classification system; it is a historical narrative of the "death of the real."

The four stages of the sign, charting the progression from a faithful representation of reality (a pumpkin) to a pure simulacrum with no real-world referent (an artificially flavored creamer). This illustrates the decay of meaning as an object moves from use-value to pure sign-value.

Use-Value: The Object's Practical Function

The first logic of value is the most concrete: an object's use-value is its practical function. A coat has use-value because it provides warmth; a hammer has use-value because it drives nails. In this logic of practical operations, the object is an instrument, and its worth is tied directly to its utility. This stage corresponds to Baudrillard's first order of the image, which he calls the "sacramental order". Here, the sign is a faithful reflection of a basic reality—a map that accurately represents the territory, a photograph that documents a real person or event. The relationship between the sign and what it signifies is clear and trusted. The object is valued for its function, and the sign is a faithful copy.

Exchange-Value: The Object's Market Price

The second logic introduces a layer of abstraction. Exchange-value refers to an object's economic value in the marketplace, its equivalence to other commodities, typically expressed in money. While a coat's use-value is keeping someone warm, its exchange-value might be $100. In this logic of equivalence, the object becomes a commodity, interchangeable with any other object of the same price. This stage aligns with Baudrillard's second order of the image, the "order of maleficence," where the sign begins to mask and pervert reality. It is an unfaithful, distorted copy. An advertisement, for example, might use an image to falsely claim a mass-produced sauce has "real cookout flavour," distorting the reality of its industrial origin. The sign no longer reflects reality but actively manipulates it. The object is now valued primarily for its market price.

Sign-Value: The Object's Status and Social Meaning

Here we arrive at Baudrillard's crucial intervention and the engine of modern consumer society: sign value. This is the value an object possesses within a system of signs, conferring status, prestige, or identity upon its owner. Sign-value operates on a logic of difference. A luxury handbag is not primarily valued for its ability to hold items (use-value) or its production cost (related to exchange-value), but for what it signifies about its owner in relation to someone with a different, or no, handbag. Consumption is no longer about satisfying needs but about social differentiation. The object's role is now that of a sign. This corresponds to the third order of the image, the "order of sorcery," where the sign masks the absence of a profound reality. The sign pretends to be a faithful copy, but there is no original referent. A fire drill simulates a fire that does not exist; a luxury brand sells a lifestyle that is pure artifice, a crisis diagnosed in detail by Dana Thomas. The object is valued for the status it confers, and its sign masks an absence.

The Simulacrum: The Sign with No Connection to Reality

The final stage marks the complete implosion of meaning. The sign now bears no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum. It no longer reflects, perverts, or even masks the absence of reality—it has entirely replaced it. In this fourth order, signs only refer to other signs in a closed, self-referential loop. This is the stage of hyperreality, where the distinction between the sign and the real is not just blurred but abolished. The true "product" of late capitalism is not the commodity but the simulacrum itself. The system no longer needs to produce real things with real utility; it thrives by producing signs of reality, signs of status, and signs of desire, which we consume as if they were real.

Standing in opposition to these logics of commodification is a fifth, more archaic logic that Baudrillard identifies as a site of potential resistance: Symbolic Exchange. Governed by a logic of ambivalence, this form of value is embodied in the symbol or the gift. Unlike the other forms of value, which are tied to utility, markets, or status, symbolic exchange is about the social bond an object creates. Its value is non-commodifiable and personal, rooted in ritual and relationship. This concept, which operates outside the system of signs, will become crucial later in our discussion of resistance to the hyperreal.

Welcome to the "Desert of the Real": Defining Simulacra and Hyperreality

Having established the decay of the sign, we can now explore Baudrillard's most celebrated and challenging concepts. He defines simulacra as copies that have no original in reality, and simulation as the process by which these copies come to replace and even generate the real world. This process unfolds across three historical orders.

First-Order Simulacra: The Counterfeit (The Obvious Copy)

Associated with the pre-modern era from the Renaissance to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the first order is that of the counterfeit. The simulacrum here is an imitation, like a stucco sculpture mimicking marble or a fake piece of art. Crucially, in this order, a clear distinction between the original and the copy is always maintained. The sign is understood as a representation—even a false one—of a "profound reality" that exists independently of it.

Second-Order Simulacra: The Production (The Mass-Produced Object)

The Industrial Revolution ushers in the second order of simulacra, governed by production. With the advent of mass reproduction, the distinction between the original and the copy begins to collapse. An object from an assembly line is a copy for which no true original exists; every instance is identical. Here, signs become repetitive, and the line between reality and its representation starts to blur dangerously.

Third-Order Simulacra: The Simulation (The Model That Precedes the Real)

The third order belongs to our postmodern, media-saturated age. It is defined by simulation, where the relationship between the sign and reality is inverted. In what Baudrillard famously calls the "precession of simulacra," the model now comes before the real. The simulation precedes and generates the territory it is supposed to represent. Media events, like the televised coverage of the Gulf War, become more real and definitive than the messy, inaccessible reality of the conflict on the ground. Scientific models no longer describe reality but create the reality they claim to analyze. Our experience of the world is increasingly an experience of these generative models.

Hyperreality: When the Map Replaces the Territory

Hyperreality is the terrifying destination to which the third order leads. It is the state in which the distinction between the real and the simulation has not just blurred but completely imploded. To explain this, Baudrillard masterfully co-opts a fable by Jorge Luis Borges. In the story, the cartographers of an empire create a map so detailed and precise that it is the same size as the empire itself, covering the territory point for point. Eventually, subsequent generations find the map useless and leave it to rot in the desert.

Baudrillard performs a brilliant inversion of this fable to describe our contemporary condition. "The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it," he writes. "It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory... that engenders the territory". Today, the simulation (the map) has become the real, and it is the physical world (the territory) whose tattered vestiges now rot away beneath it. We are living in what he calls "the desert of the real," mistaking our media-generated, sign-saturated world for reality itself.

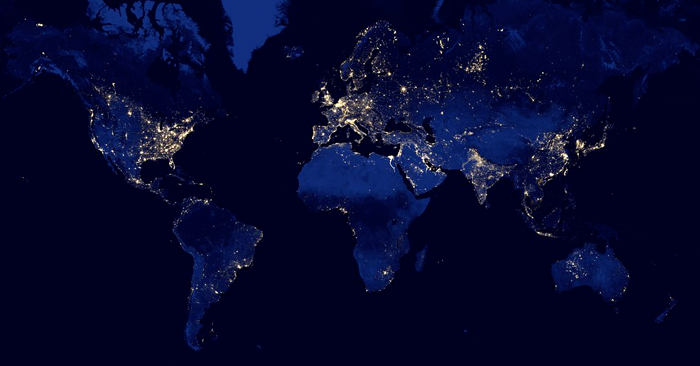

Baudrillard argued that the 'map' of simulation now generates the 'territory' of the real. This view of Earth visualizes this hyperreality, where the glowing network of human signs and systems becomes more real and definitive than the dark, physical landmass it covers.

Disneyland is Baudrillard's classic example. It presents itself as an imaginary world to make us believe that the America outside its walls is "real." In fact, he argues, Disneyland's function is to hide the fact that the "real" America is itself a simulation, a third-order simulacrum just as orchestrated and artificial as the theme park. The power of hyperreality is that it eliminates the very ground from which it could be critiqued. If there is no "real" to compare the simulation to, then the simulation becomes our only reality. Asking "what is hyperreality explained?" is to ask about a world where the question "is this real?" has become meaningless.

Case Study: How Modern Luxury Became Hyperreal

The modern luxury industry serves as a perfect case study for Baudrillard's theories. It is an industry that has mastered the art of third-order simulation, no longer selling well-crafted objects but rather trafficking in a hyperreal code of signs.

The Logo as Floating Signifier: The Case of the Luxury Handbag

The semiotics of the luxury logo reveals this transition with stark clarity. Historically, many logos signified a specific heritage, craft, or story—the Hermès horse-and-carriage, for instance, is a direct reference to its origins as a harness and saddle maker. Today, however, a dominant trend has seen major fashion houses like Burberry, Yves Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga abandon their distinctive typography for minimalist, geometric, sans-serif logos that are nearly indistinguishable from one another.

The aesthetic convergence of major luxury logos, often called 'blanding,' is a visual symptom of the logo's transformation into a floating signifier. Stripped of their unique historical typography, they no longer refer to a specific heritage but to their interchangeable position within the abstract code of 'luxury.'

This aesthetic convergence is more than a concession to digital legibility. It is the transformation of the logo into what has been called an "empty container". Stripped of specific historical meaning, the logo becomes a floating signifier. It no longer refers to the quality of the object, the history of the maker, or the skill of the artisan. Instead, it refers only to its own position within the abstract code of "luxury." The luxury handbag is the quintessential example. Its astronomical price has little to do with its utility (use-value) or even the cost of its materials and labor (exchange-value). Its value is almost entirely its sign value: a pure signifier of status within the hyperreal system of Baudrillard fashion.

The Influencer Economy and Simulated Desire

This hyperreal system is powered by a new engine of desire: the influencer economy. Influencers do not simply advertise products; they produce and perform aspirational lifestyles that are pure simulation. Through curated images and videos, they construct a seamless hyperreality of leisure, beauty, and effortless consumption, in which luxury objects appear as casual props. This was laid bare in the viral case of Wisdom Kaye and The Miu Miu Problem.

The influencer economy generates a closed loop of simulated desire. Here, a luxury handbag appears as a prop in a constructed hyperreality of effortless glamour, explicitly marked as an advertisement (#adv). Consumption is driven not by the object's function, but by the desire to enter the simulated world the image represents.

Followers are not primarily consuming the product, but the sign of the lifestyle it is embedded within. This creates a closed loop of simulated desire that perfectly illustrates the precession of simulacra. The simulated lifestyle (the map) precedes and generates the desire for the object (a coordinate on the map). The desire is not for the thing itself, but for entry into the simulated world the influencer represents—a world that has no real-world referent.

Economic Value vs. Semiotic Value: Two Models of Luxury

This shift from object to sign requires a new model for understanding luxury's value. The standard economic definition of a luxury good is a product with a high positive income elasticity of demand, meaning that as a person's income rises, their spending on that good increases by a greater proportion. A 1% rise in income might lead to a 2% rise in spending on luxury cars, for example.

While technically accurate, this economic model is profoundly insufficient. It describes a correlation—that people with more money buy more luxury goods—but it fails to explain the motivation, the why. Baudrillard's semiotic model provides the missing explanation. In a society of abundance where basic needs are met, consumption becomes a primary means of social differentiation. We buy luxury items not for their superior utility but for the status they signal within a social code. The economic model is obsolete as a tool for understanding motivation because the true driver of luxury consumption is the acquisition of sign value. The luxury industry has successfully replaced the territory of well-crafted, durable objects with the map of a constantly shifting code of logos and simulated lifestyles. The consumer does not purchase a product; they purchase a position on this map. This is the hollowed-out, hyperreal state of modern luxury.

The Resistance: Symbolic Exchange and Post-Luxury Art

If modern luxury is a terminal disease of meaning, is there a cure? Baudrillard's own work, often seen as deeply pessimistic, contains the seed of an answer. He contrasts the logic of commodity exchange with a more archaic, powerful, and disruptive logic: symbolic exchange. It is this very concept that provides the philosophical foundation for Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA) as a tangible form of resistance.

Beyond Commodity: The Power of Symbolic Exchange

Unlike commodity exchange, which is based on economic equivalence, calculation, and profit, symbolic exchange is a social logic based on reciprocity, ritual, and the creation of relationships. Its quintessential example is the gift. The value of a true gift is not its market price but the social bond it establishes and maintains between the giver and the receiver. It is personal, non-fungible, and operates outside the logic of capital. As one analysis notes, you would never trade a wedding ring for a "nicer" or more expensive one, because its value is symbolic and tied to a unique relationship and ritual; it is not a commodity to be upgraded. Symbolic exchange is an act that, by its very nature, cannot be commodified. It breaks the code.

PLCFA as a Tangible Anchor in a World of Signs

This detailed view of a Japanese boro jacket serves as a tangible example of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art. Its value is derived not from a floating signifier or logo, but from its visible narrative of repair, its unique and permanent construction, and the craft of the human hand. It is an object whose meaning deepens with age, an anchor of symbolic exchange in a world of disposable signs.

The philosophy and practice of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art can be understood as a deliberate effort to reintroduce the logic of symbolic exchange into a world saturated by empty signs. As a movement that rejects status symbols in favor of meaning, its core principles directly counter the hyperreality of modern luxury.

First, by insisting on Utility as an Essential Foundation, PLCFA restores use-value to a central, dignified position, resisting the absolute dominance of the sign. An object must first do something, grounding it in the real world of practical action.

Second, PLCFA prioritizes Narrative Over Material. The value of a PLCFA object derives not from a logo or the market price of its components, but from its unique story, its ethical provenance, and the maker's intention. It is conceived as an "artifact for a life," not a product for a season. This transforms the object from a commodity into something akin to a gift or a ritual object, whose meaning deepens over time, a concept explored in The Art of Being.

Third, a commitment to Permanence and Resistance to Replication stands in direct opposition to the planned obsolescence and trend-driven cycles of the fashion simulacrum. These objects are made to endure, to absorb the patina of years and bear witness to a life.

In acquiring a PLCFA object, the owner does not engage in a simple act of consumption. They become a "steward" or "custodian" of its ongoing narrative, entering into a personal and reciprocal relationship with the object. This act is a form of symbolic exchange. A PLCFA object's value cannot be reduced to a sign within a code. It cannot be simulated, because its value resides in its unique history, its tangible function, and the personal relationship it fosters. It resists the logic of equivalence that governs both the market and the hyperreal, much like the covert art interventions of The Secret Handshake seek to break political codes.

Therefore, PLCFA is the antidote to the "desert of the real." In a world where luxury has become a copy without an original, a PLCFA object is a defiant original whose authenticity is guaranteed by its story and its purpose. It is a piece of the territory that refuses to be replaced by the map. It offers a path out of the hall of mirrors and a way to re-engage with a world of tangible, meaningful things.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.