The "Monopoly on a Vibe": Why the Louis Vuitton vs. Coogi Lawsuit is the Final Collapse of Luxury's Sign System

The legal proceeding Coogi Partners, LLC v. Williams et al. (Case 1:25-cv-03837), filed in the Southern District of New York on May 8, 2025, represents a fundamental crisis in the logic of luxury. This is not a conventional dispute over the material production of a garment. It is a spectacle of semiotics, a legal battle over the ownership of a "sign" that has become fully detached from its physical referent. The lawsuit, which alleges that Louis Vuitton's Fall/Winter 2025 collection, designed by Pharrell Williams and NIGO, misappropriated Coogi's iconic knitwear designs, is the "end game" of the hyperreal logic that has long governed the fashion industry.

A visual comparison of the Louis Vuitton F/W 2025 design (left) and the Coogi knitwear (right). The legal dispute is not over the material object, but over the "vibe" and "sign system" that the designs represent.

The physical sweaters, the ostensible objects of the dispute, are irrelevant. The true locus of the conflict is the "vibe." This is immediately evident in the widespread media reaction to the Louis Vuitton show, which described the garments not as copies, but as "Coogi-flavored" and "virtually identical". This linguistic choice is the critical diagnostic of a hyperreal shift. The suffix "-flavored" or "-style" demonstrates that "Coogi" has culturally transcended its status as a product and now functions as an abstract aesthetic category, an essence, or a "vibe" that can be applied to other objects. Coogi's lawsuit, therefore, is a literal attempt to claim legal ownership over this abstract essence, a concept that stands in stark contrast to the Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art framework.

This legal battle exposes the central contradiction of the entire luxury system. The ultimate irony is that Louis Vuitton, a $200B+ empire built on the aggressive legal enforcement of its own "monopoly on a vibe"—the Toile Monogram, the Damier check —is now positioned to argue against the legal protection of an aesthetic. This lawsuit is the moment the system, built on the monopolization of signs, collapses under the weight of its own hypocritical logic.

The Political Economy of the Sign: Baudrillard and the Logic of Luxury

To understand the profound nature of this crisis, one must first understand the theoretical framework of the luxury system as defined by the post-structuralist philosopher Jean Baudrillard. In works such as For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, Baudrillard articulates four distinct logics of value that govern objects: 1) functional use-value; 2) economic exchange-value; 3) symbolic exchange-value; and 4) semiotic sign-value.

The post-structuralist philosopher Jean Baudrillard, whose work For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign provides the theoretical framework for understanding the luxury system. Baudrillard argued that modern luxury operates on "sign-value," where the brand and its logo (the sign) become more valuable than the physical object itself, a concept central to the Coogi v. Louis Vuitton dispute.

The modern luxury industry operates almost exclusively in the fourth realm, that of sign-value. As Baudrillard's analysis posits, consumption in modern society is "the sign consumption, difference sign mark value... not the consumption of things as used value". Luxury goods are not items of utility but a "linguistic code". The system of "new prestigious goods" functions through "symbolic codes, which prioritize differentiation and novelty to sustain perpetual consumption cycles".

The progression of luxury maps perfectly onto Baudrillard's "orders of simulacra":

First Order (Reflection of Reality): The original Louis Vuitton trunk. It is a "basic reflection of reality" , a functional, high-quality object designed for travel. Its value is tied to its use.

Second Order (Perversion of Reality): The Monogram. Created in 1896 , the sign begins to "mask" this "profound reality". The "artistry" and "craftsmanship" serve as an alibi for the sign's true function: to represent wealth and status, a hollowing out of meaning previously diagnosed in "The Luster Restored".

Third Order (Hyperreality): The modern luxury system. Here, the sign "bears no relation to any reality whatsoever". The map precedes the territory. The Louis Vuitton brand is the reality. Its value is not in the object, but in its position within a "closed system of fabricated signs".

In this system, fashion becomes what Baudrillard, in Symbolic Exchange and Death, called the "enchanting spectacle of the code". It is a "self-referential system" where "commodities derive meaning through relational differences". The consumer, "overpowered by consumer values, media ideologies and role models" , experiences the "end of the individual".

Within this framework, the modern luxury brand does not sell products; it constructs and sells "symbolic hegemony via proprietary emblems". The Monogram is the primary tool of this hegemonic control. Any threat to this control—be it a counterfeit or a parody —is not merely an economic threat but an ideological one. It challenges the integrity of the code. Therefore, Louis Vuitton's "zero tolerance policy" , its employment of 250 agents, and its management of over 18,000 intellectual property rights must be understood as semiotic policing. It is the necessary, aggressive enforcement required to maintain its dominance within the "closed system" and "exterminate" any sign that is not its own.

The Architects of the Vibe: A Semiotic History of the Litigants

The Coogi v. Louis Vuitton case is a battle between two powerful, constructed "vibes," each with its own history of semiotic simulation.

A: Coogi: From Souvenir to "Signifier of Opulence"

Coogi's journey from a material object to a pure sign follows Baudrillard's orders of simulacra perfectly.

The "Profound Reality" (First Order)

Coogi's history begins in 1969 as "Cuggi" in Toorak, Australia. Its initial purpose was to serve as a souvenir for American and European tourists. Its "profound reality" was its "Australian roots" , with its signature patterns explicitly inspired by the "Australian wilderness" and "Australian Aboriginal artwork".

The Simulation (Second Order)

The brand's value soon began to detach from this reality through two key acts of simulation. The first, a foundational act of simulation, occurred in 1987. The brand changed its name from "Cuggi" to "Coogi" for the specific purpose of making it "closer resemble an Indigenous Australian name". This was a conscious manipulation of the signifier to create a simulacrum of deeper, more exotic authenticity. It was not actually indigenous; it was designed to sound indigenous, thereby increasing its sign-value as an Australian artifact. This was followed by its adoption by Bill Cosby, where the sweater's sign-value shifted again, masking its "Australian souvenir" reality to become a "symbol of the elite, usually white, world traveler" and, subsequently, a "status symbol" for a "middle-class African-American TV dad".

The Simulacrum (Third Order)

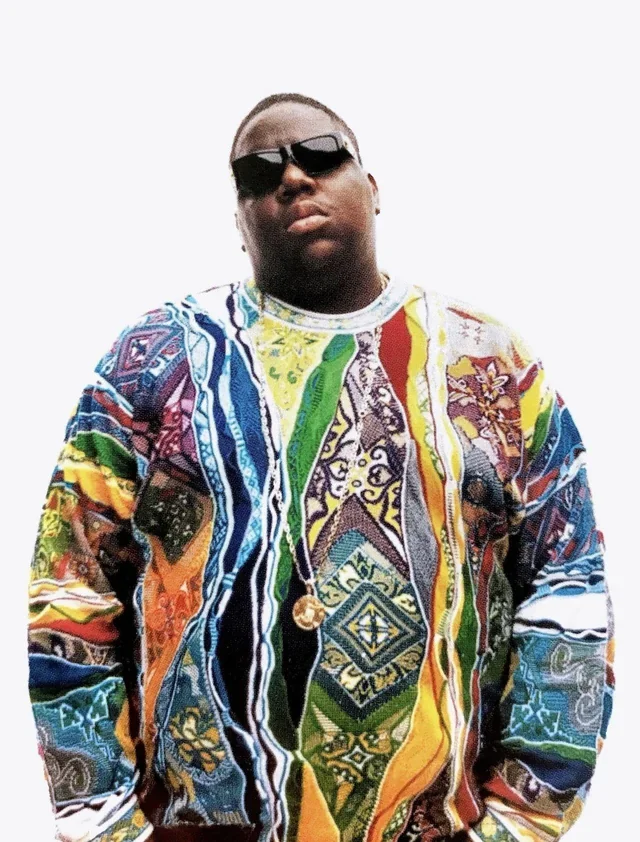

The brand's entry into the third order of hyperreality was cemented in the 1990s through its adoption by hip-hop culture, most notably by The Notorious B.I.G.. His lyrics—"Living better now, Coogi sweater now" and "I stay Coogi down to the socks" —were semiotic acts that created a new reality for the brand. The sweater's value was no longer tied to Australia or Cosby's elite status; it was now a pure signifier of "opulence" and success within the hip-hop semiotic system.

The artist Jayson Musson provides the definitive confirmation of this hyperreal status. He notes that for his generation, "the garment existed only as an image, as a signifier of opulence". The "loud" visual code and its high price (up to $700) were all that mattered. The physical sweater was irrelevant; its sign-value was total.

B: Louis Vuitton: The Empire of the Monogram

Louis Vuitton's history is different. Its primary sign, the Toile Monogram, was born a simulacrum. It was created by Georges Vuitton in 1896 with no "profound reality" other than its function as a sign; it was explicitly designed as an anti-counterfeiting measure. Its origin is its function as a unique signifier.

From this semiotic origin, Louis Vuitton built its $200B+ empire as a legal and economic construct designed to protect its sign-value, a strategy previously analyzed in the Art Basel's Spectacle critique. As noted, its Intellectual Property Department is its most critical division, managing a vast portfolio of 18,000+ rights. Its "divide and conquer" strategy involves registering not just the Monogram as a whole, but the "individual elements of a pattern" to ensure total semiotic control.

This "admittedly 'aggressive' approach to enforcement" is the necessary "policing" of its simulation. Its litigation history reveals a pattern of attempting to secure this total monopoly:

Damier Canvas

Louis Vuitton waged a multi-year, successful battle to have its Damier check pattern recognized as a "trademark" with "primary distinctiveness," arguing it was not merely a "decorative" pattern.

Parody and Satire

The brand's power is not, however, absolute. It famously lost its case against My Other Bag (MOB), when courts upheld MOB's "designer bag-on-a-canvas" tote as a protected parody. Similarly, MGA's "Pooey Puitton" case, though dismissed in the U.S. on jurisdictional grounds, highlighted LV's "history of not respecting parody rights".

Louis Vuitton famously lost its case against My Other Bag (MOB) when courts upheld MOB's "designer bag-on-a-canvas" tote as a protected parody. This case, along with the "Pooey Puitton" dispute, represents a significant "crack in the simulation"—a legal precedent where LV's absolute control over its sign-value was successfully challenged.

These legal setbacks, particularly its more recent losses, are not just isolated failures; they are "cracks in the simulation." The most significant of these is the Damier Azur case, where the EU General Court ruled that Louis Vuitton failed to prove its light-colored checkerboard pattern had "acquired distinctive character through use throughout the European Union". The court explicitly refused to grant a monopoly over what it deemed a "non-conventional... pattern mark". This ruling, which established the legal fragility of LV's own aesthetic monopoly, provides the very precedent and logic that Louis Vuitton will now, in an act of supreme irony, be forced to use in its own defense against Coogi.

Coogi v. Louis Vuitton: The Spectacle of the Collapsing Code

The lawsuit Coogi v. Louis Vuitton is the moment the system's contradictions become fatal. It is the spectacle of the code turning on itself.

A: The Allegation: Theft of a Simulation

The legal complaint filed by Coogi is a fascinating document, as it is forced to "simulate" a legal claim that the U.S. intellectual property system is ill-equipped to handle. The real grievance is "Louis Vuitton stole my vibe," but this is not a recognized cause of action. Therefore, the complaint presents a bifurcated argument:

The "Real" Claim (Copyright)

Coogi alleges infringement of its specific copyright-registered "RAG & BONE" sweater design. This is the "reality-based" legal hook. However, it is also the weakest claim, as fashion designs are notoriously difficult to protect under U.S. copyright law due to the "useful article" doctrine, which limits protection for the design of functional items like clothing.

The "Hyperreal" Claim (Trade Dress)

This is the true battle. Here, Coogi is suing over its "vibe." The complaint attempts to legally codify this vibe, defining its trade dress as: "a central section... [with] highly colorful individual vertical cables and ornamented sections," "sleeves showing horizontally the same colors and intricate designs," and a "raised knit that appears three-dimensional".

The evidence submitted for this claim is a perfect Baudrillardian loop. To prove "secondary meaning" and consumer confusion, Coogi's complaint cites the media reactions—the use of terms like "Coogi-flavored" and "Coogi-inspired". In this hyperreal circuit, the spectacle's (media) reaction to the simulation (the LV sweater) is presented as evidence in a "real" (legal) proceeding.

B: Pharrell Williams as the Alibi of Authenticity

Pharrell Williams's role as Men's Creative Director is not to design in the traditional sense, but to signify. His appointment, criticized for his "lack of a formal design education," signaled a shift. He functions as a "curator" or "semiotic DJ," lending an "aura" of cultural authenticity to the brand. As a revered cultural icon, his presence serves as the perfect alibi, masking the "appropriation" of vernaculars (like the Coogi knit) as a simple act of "cultural remixing."

His strategy is one of "cultural remixing" , bringing the "wider cultural associations (think a Y2K 50 Cent or Kanye West) onto the runway". The alleged Coogi "copy" is not an anomaly; it is the perfect expression of this strategy. This is confirmed by Pharrell's own profound self-characterization, in which he stated he sees himself as "less of a creative director and more of a client". His goal is to serve the "LVover" , a fellow "lover" of signs and details.

This is the "end of the individual" creative genius. In his place is the curator , the semiotic DJ who "remixes" pre-existing signs from the "closed system". The alleged Coogi copy is not a failure of his creativity; it is the purest expression of his actual role. Furthermore, as a revered Black cultural icon, Pharrell's presence functions as the perfect alibi. He masks the problematic "appropriation" of "historically Black fashion vernacular," a form of mining what has been termed "artistic dark matter" in "The Missing Mass."

C: The Defense as Confession: "A Monopoly on a Vibe"

Court dockets for Case 1:25-cv-03837 from July to October 2025 confirm that Louis Vuitton, Pharrell, and NIGO are filing a "MOTION to Dismiss First Amended Complaint". The core of this motion, as anticipated by the thesis, must be that Coogi is attempting to improperly "monopolize an aesthetic" or "a vibe."

This defense is the climax of the crisis. It is a stunning, confession-by-proxy. Louis Vuitton, the $200B+ empire built on a legally-enforced "monopoly on a vibe" (the Monogram) , will now argue in federal court that such monopolies are anti-competitive, stifle creativity, and are legally impermissible. This is the ultimate hypocritical act: the master of the sign argues that signs should be free, but only when they want to use them. It exposes the brand's entire "protection of creativity" platform as a hollow alibi for market control.

This anticipated defense is not just cultural hypocrisy; it is legally sound. Louis Vuitton's lawyers will almost certainly draw upon the "aesthetic functionality" doctrine. This doctrine argues that an aesthetic feature (like a color or pattern) that is functional (i.e., it is the reason consumers buy the product, independent of the source) cannot be monopolized, as this "would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage". LV will argue that Coogi's "colorful, 3D knit" is an aesthetic and thus functional in a competitive sense, and therefore unprotectable.

The final, fatal irony is that to make this argument, Louis Vuitton must cannibalize its own legal-semiotic foundation. It will be forced to use its own legal failures (like the Damier Azur case ) and its competitors' legal victories (like Thom Browne's "Adidas does not own stripes" defense ) as the ammunition for its motion to dismiss. To win against Coogi, Louis Vuitton must argue against itself.

The Precedent: A Legal System Confronts the Aesthetic

The Coogi v. LV case is the culmination of a systemic crisis. The legal system has been increasingly struggling to apply traditional intellectual property concepts to abstract aesthetics, or "vibes." This battle is simply the latest and most acute symptom of a larger pattern.

The battle over a single color was fought in Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent. The case resulted in a notable compromise: the court granted Louboutin a limited trademark monopoly, but only for situations where the signature red sole contrasts with the color of the shoe's upper. Because YSL's shoe was entirely red, it did not infringe. This ruling demonstrated the court's deep discomfort with granting a total monopoly on a single color in the fashion space. Louboutin has faced similar struggles globally, with a French court once invalidating the trademark for being "too vague" and a Japanese court later denying infringement claims by stating red is a "common aesthetic enhancement".

A more direct precedent for Louis Vuitton's defense is Adidas America, Inc. v. Thom Browne, Inc.. This was a high-profile battle over the "vibe" of parallel stripes. Adidas, a giant that aggressively protects its three-stripe mark, sued Thom Browne for trademark infringement and dilution over his "Four-Bar Signature". Browne’s defense was a direct assault on the "monopoly on a vibe" concept; his attorney famously began his closing argument with the simple, powerful statement: "Adidas does not own stripes". In January 2023, a jury agreed, handing a resounding victory to Thom Browne and establishing a clear legal and cultural precedent that an aesthetic element as basic as stripes cannot be indefinitely monopolized.

Lululemon's legal battles illustrate a different tactic: the use of design patents to protect an aesthetic. Its 2012 suit against Calvin Klein over the "Astro Pant," which alleged infringement of its design patents , was a direct challenge to the fashion industry's traditional "trickle-down" culture of appropriation. That case was settled confidentially. Lululemon has continued this aggressive protection of its "vibe," later suing Peloton and Costco for selling "knockoff" apparel that allegedly infringes its trade dress. This demonstrates a corporate understanding that the "vibe" is the asset, requiring protection through any legal means available.

Most recently, the "Sad Beige" lawsuit (Gifford v. Sheil) demonstrates the "vibe" concept taken to its abstract conclusion. Here, an influencer sued another for allegedly co-opting her entire aesthetic, which she defined in her trade dress claim as a "monochrome palette of cream, grey, and beige," "minimalist modern backdrops," and a "relatable tone". This was a literal attempt to monopolize an entire mode of being. The case was significant because a magistrate judge allowed the core trade dress claims to proceed before the parties ultimately settled, signaling that the legal system is beginning to seriously entertain these highly abstract claims.

These cases, from color to stripes to an entire influencer "vibe," create the fragmented and contradictory legal landscape that Coogi v. Louis Vuitton now enters. This lawsuit is the "boss level" of aesthetic litigation. It combines the legal questions of all prior cases: it is a battle over a specific, copyright-registered design (the "RAG & BONE" sweater) , but also, more importantly, over a trade dress defined by a complex combination of color, pattern, and texture. It is a fight over an aesthetic that is also a "culturally significant visual code" , all of which is pending as Louis Vuitton has filed its motion to dismiss.

The End Game of Hyperreality

This analysis synthesizes the collapse of the luxury sign system. This system, built on Baudrillardian sign-value , has evolved into a "closed system of fabricated signs". To maintain its "symbolic hegemony" , this system requires a legal framework—intellectual property law—to grant and enforce its monopolies on signs.

However, as the signs have become more abstract, detaching from objects to become "vibes" and "aesthetics," the legal framework has begun to fail, as evidenced by the Adidas v. Thom Browne and Damier Azur cases. The Coogi v. Louis Vuitton lawsuit is the system's final, cannibalistic phase.

The master of the sign (Louis Vuitton) is forced to argue against the very principle of sign-monopoly to defend its own act of simulation (the alleged "Coogi-flavored" copy). Pharrell Williams, the "client" director , is the agent of this simulation, and Coogi, the "signifier of opulence" , is the sign being simulated.

This is the "battle of signs" in its purest form, the very crisis of value the Post-Luxury paradigm seeks to resolve. The conflict is no longer between the brand (Louis Vuitton) and the counterfeit (a first-order copy). It is a battle between sign and sign (the LV Monogram vs. the Coogi knit) within the closed loop of the code. The "profound reality" is gone. The physical sweater is irrelevant. The only thing of value, the only territory left to fight over, is the simulation itself. This is the end game of hyperreality.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.