The Bag-Backed Security: How the LUXUS Fund Signals the Death of Old Luxury and the Rise of the Post-Luxury Era

The 21st century has borne witness to a silent, seismic shift in the semiotics of value. Luxury—once the bastion of craftsmanship, heritage, and ineffable savoir-faire—has been systematically hollowed out, its cultural meaning evacuated and replaced by a new, cold, and relentlessly quantitative logic. The alternative asset has supplanted the object of affection. This transformation was not an accident; it was a deliberate, institutional project to financialize desire, to codify taste, and to render the intangible liquid. What was once a Veblen good, whose value was derived from its conspicuous consumption and social sign-value, has been formally re-positioned as a securitizable asset class, indistinguishable in its portfolio function from real estate, private equity, or gold.

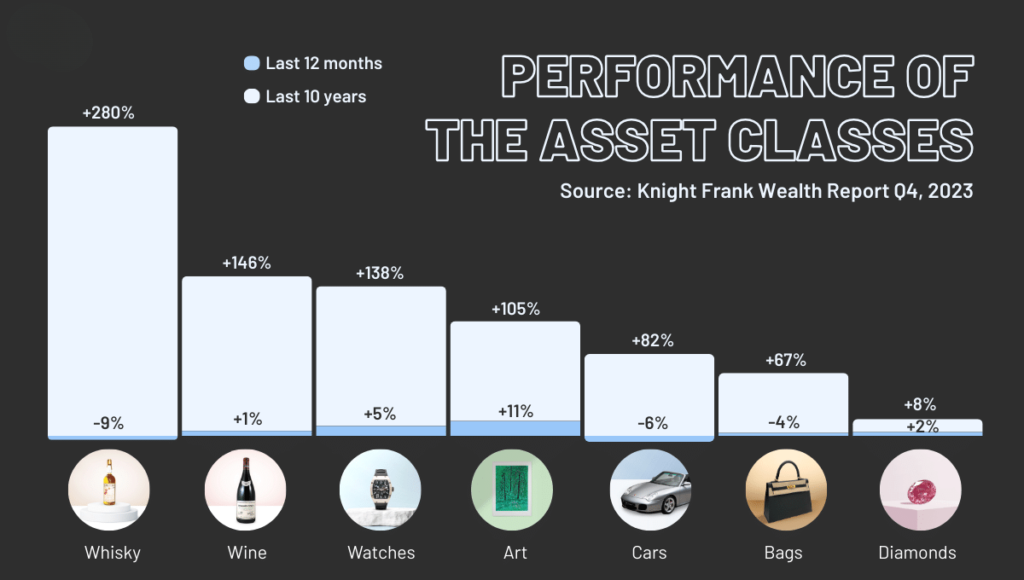

This shift is no longer a niche theory but a dominant strategy for the world's financial elite. The 2024 Knight Frank Wealth Report, a key bellwether for Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals (UHNWIs), revealed that a staggering 70% of this cohort had "increased their allocation to luxury investments" over the preceding year. A newfound appreciation for artisanship does not drive this capital migration. It is propelled by a search for strong returns and, crucially, for assets that are uncorrelated with the volatility of traditional financial markets. The central thesis, articulated by wealth managers and alternative investment platforms, is that tangible assets like art, diamonds, and high-end handbags often retain or even increase in value during economic downturns.

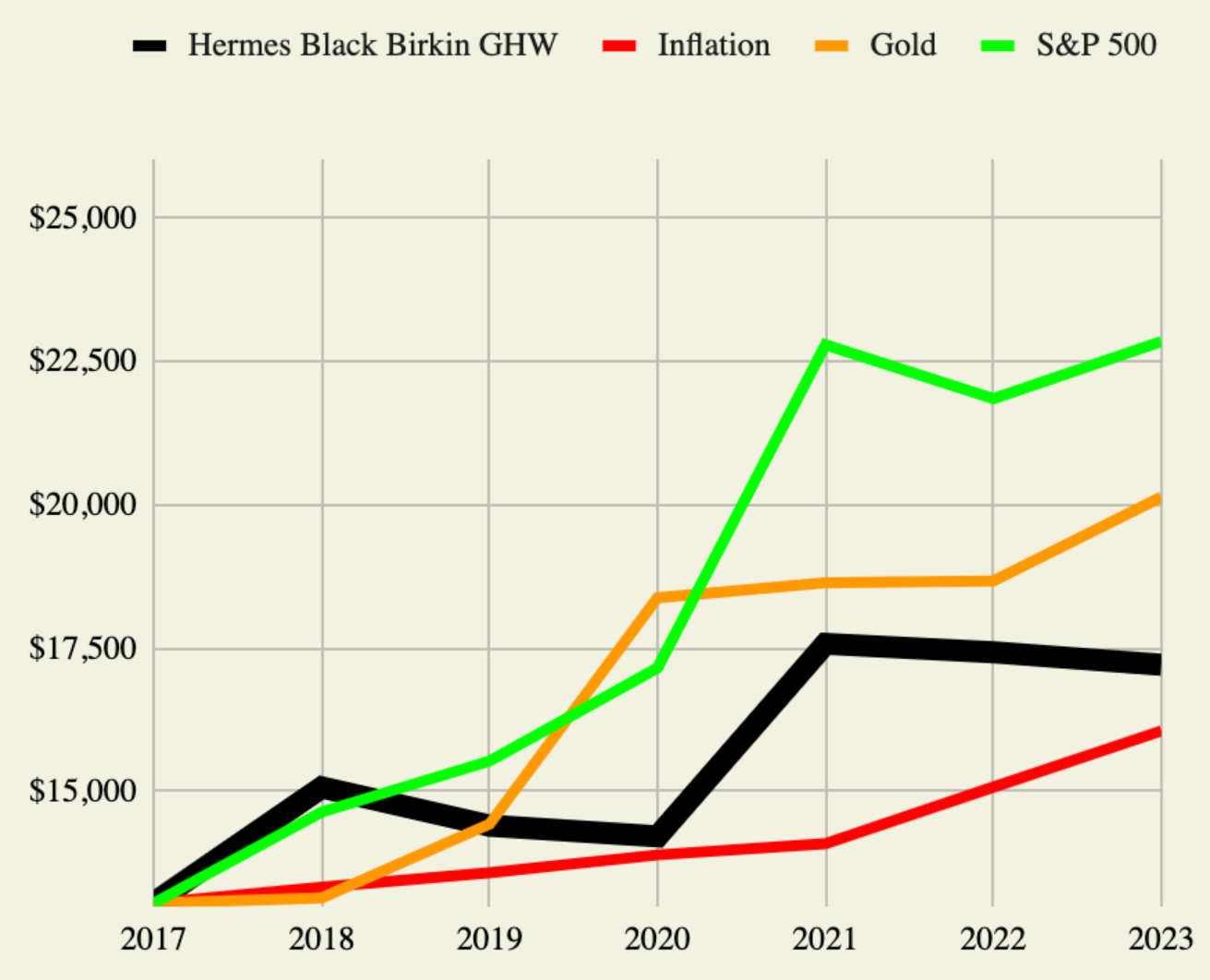

This financialization has created an entire ecosystem of analysis, replete with its own indices, reports, and academic justifications. The performance of luxury categories is now charted with the same rigor as stocks and bonds, with reports from firms like Splintinvest and FashioNica dutifully comparing the five-year appreciation of a Chanel Classic Flap bag against the S&P 500 or the monthly volatility of a Rolex against the STOXX 50. This is not a mere comparison; it is a re-definition. It subsumes the object entirely into the language of finance, where its only legible qualities are its growth rate and its risk profile.

The modern financial ecosystem reframes luxury objects, charting their volatility and appreciation with the same rigor as traditional stocks and bonds.

This perspective has deep roots in academia, which has long provided the intellectual framework for this detachment. A 2004 paper in the Journal of Finance titled "Luxury Goods and the Equity Premium" did not analyze luxury for its cultural import, but instead used novel data on the consumption of luxury goods as an econometric tool to analyze the risk aversion and portfolio-choice behavior of the wealthy. For the financial world, luxury items are not objects but data points that illuminate market behavior. This same logic now dominates the corporate boardroom. The strategy of Building the Balance Sheet in the Fashion and Luxury Goods Industry is a formal priority, with private capital flowing into the sector not just to sell products, but because luxury brands themselves are seen as a solid long-term investment. Firms are now advised to leverage the intangible value of their brands and intellectual property as innovative financing options.

Yet, this entire financial edifice is built on a foundational myth. The relentless marketing of luxury as a stable, appreciating asset class masks a deeply contradictory and volatile reality. The "passion investing" narrative is precisely that: a narrative. While platforms like Konvi, which sells fractional shares in Birkins, boldly claim the bags have "never fluctuated downwards in value", the industry's own data refutes this claim entirely. The very same 2024 Knight Frank report that trumpeted UHNWI interest also showed that, as an asset, handbags had lost value, posting a -4% return. A 2025 study by FashioNica found that, over five years, logo'd pieces like the Chanel Classic Flap bag underperformed the S&P 500. Furthermore, a 2024 analysis of the luxury watch market revealed a decline of nearly 8%, in stark contrast to the growth of traditional indices like the SMI and STOXX 50.

The passion investing narrative often masks a volatile reality. Industry data, such as this 2023 Knight Frank report, shows key luxury sectors like handbags posting negative returns.

This reveals the first and most profound detachment. The primary product being sold is not the asset's consistent performance, but the myth of its performance. 70% of UHNWIs are not buying handbags; they are buying a story about stability in a time of uncertainty. The financialization of luxury is, therefore, the financialization of a feeling. The object is merely the collateral for a narrative. This critical separation—between the financial story being told and the object's actual, volatile market behavior—created fertile ground for the ultimate abstraction: a system in which the object itself would no longer be necessary at all.

The Engine of Abstraction: Fractionalization and the 'Democratization' of Scarcity

If the idea of luxury as an asset was the ideological spark, then fractionalization is the technological engine that enables its total dematerialization. This is the mechanism that liberates the object's financial value by, quite literally, imprisoning the object itself. The fractional ownership model is the key driver of this new market, which is projected to grow at a 15% compound annual rate. Once confined to high-value, illiquid assets like private jets and real estate, this model is now expanding aggressively into "fine art and collectibles".

The core innovations that enable this abstraction are Blockchain and Tokenization. This technology performs a kind of financial alchemy: it takes a singular, physical object—a Picasso, a Patek Philippe, or a Hermès Birkin—and digitally divides it into thousands of digital tokens. Each token, stored on a secure blockchain ledger, represents a legal share of ownership. The stated benefits of this process are, without exception, purely financial. They speak not of aesthetics, craft, or history, but of Increased Liquidity, Lower Costs, Transparency, and Global Access. This model, proponents claim, democratizes the formerly exclusive world of luxury investing.

This democratization is marketed heavily to a new generation of investors, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, who are invited to participate in a market previously reserved for the ultra-wealthy. Platforms like Lympid, for instance, allow an investor to own a share in an appreciating luxury handbag for as little as €30. This rhetoric of access and inclusivity masks a profound, paradoxical inversion of values. The traditional concept of luxury, as hollow as it became, was still predicated on use. Its "sign-value" was generated through public display, through the wearing of the watch or the carrying of the bag.

The fractional model annihilates this. What, precisely, does the €30 investor on Lympid actually "own"? They cannot see the bag. They cannot touch the bag. And most critically, they cannot wear the bag. The physical object, in fact, is a liability to its new financial purpose. To ensure the asset's value is not compromised by the friction of reality—a scratch, a stain, a single sign of wear—it must be removed from the world. As Lympid's own materials state: "All handbags in our investment portfolio are stored in a secure, insured, and climate-controlled environment in a Bank Vault". Another platform, More Luxury Club, boasts of removing the "hassles out of ownership," which it defines as "insurance, cleaning, maintenance, repair, storage, and logistics". The hassle to be eliminated, it turns out, is the entire human experience of using the object.

This is the central paradox of fractionalization: it achieves mass access to an object's financial value by ensuring mass alienation from the object's physical function. The platform does not sell fractional ownership of a handbag; it sells fractional ownership of a ticker symbol that is collateralized by a vaulted handbag. The technology democratizes the financial abstraction, not the luxury object. The object has been fully dematerialized; its use-value has been reduced to a risk that must be neutralized in a Bank Vault. The only use left is its 24/7 liquidity—a quality that is the very antithesis of a physical, tangible artifact. This is the second great detachment, paving the way for the final, hyperreal collapse.

In the fractionalization model, the physical object is a liability. Its use-value is neutralized by imprisoning it in a secure, climate-controlled environment—often a bank vault—to preserve only its financial value.

Case Study: LUXUS and the 43-Day Flip

This total abstraction from the physical object finds its purest expression in the emergence of LUXUS. This entity is not a collector, a reseller, or a fashion house. It is, by its own definition, "Luxury Alternative Asset Management". Its stated mission is not to celebrate craft, but to pursue the curation, securitization, and monetization of the world's "scarcest luxury assets". This is the explicit, undisguised language of high finance, representing the final stage of the hollowing-out process.

LUXUS is not the democratized retail-level fractionalization of a Lympid or a Konvi. It has escalated the game, targeting its investment opportunities exclusively to accredited investors. This moves the luxury object out of the realm of mere collecting and into the world of quasi-institutional high finance. The operation is given a crucial veneer of "Old Luxury" legitimacy through its most significant partner: LUXUS is backed by Christie's. This partnership is a masterstroke of semiotic laundering. Christie's, the venerable auction house, has itself spent the last decade meticulously repositioning high-end handbags away from fashion and toward investment-grade objets d'art. By backing LUXUS, Christie's provides the institutional validation and, more importantly, the liquid, high-consensus resale channel that this new financial model demands.

LUXUS represents the final stage of financialization, operating as an asset management firm "Backed by Christie's" to securitize and monetize luxury goods.

The definitive proof of this model—the "smoking gun" of total financialization—is the performance of its first fund. The MicroLEAAF: Hermés Edition 01, a $1 million fund, returned 34% in 43 days. This single data point is the obituary for "Old Luxury."

Let us be clear: this is not an investment. Investment, even in the context of passion assets, implies a long-term horizon, a stewardship that allows an object's value to mature and appreciate over years, if not generations. A 43-day holding period is the temporal logic of a high-frequency trader. A 34% return in that window is not appreciation; it is a speculative trade based on market arbitrage. This model does not care about the bag's history, its leather, or the hands that stitched it. It requires only two things: high-volume price volatility and a hyper-liquid resale market.

This is the "Bag-Backed Security" made manifest. The term is a direct analogue to the "Asset-Backed Securities" (ABS) that populate modern financial markets. An ABS is a financial instrument collateralized by an "underlying pool of assets" that are valued for their predictable "cash flow". In the LUXUS model, the asset pool comprises a curated selection of Hermès Birkin and Kelly bags. Their "cash flow" is the volatility of their resale prices. The fund, therefore, is not investing in handbags. It is trading the rapid, predictable fluctuations in their resale value.

The bag itself has become entirely irrelevant. It is a commodity chip in a high-stakes casino, a physical token whose sole purpose is to serve as collateral for a bet on its own price movement. The LUXUS model is the logical endpoint of the process. It is not selling bags; it is selling shares in the resale price of the bag. This is the total, final collapse of the object into a pure financial abstraction, an event so significant that it requires a more robust theoretical diagnosis.

The Simulacrum Made Real: A Baudrillardian Diagnosis

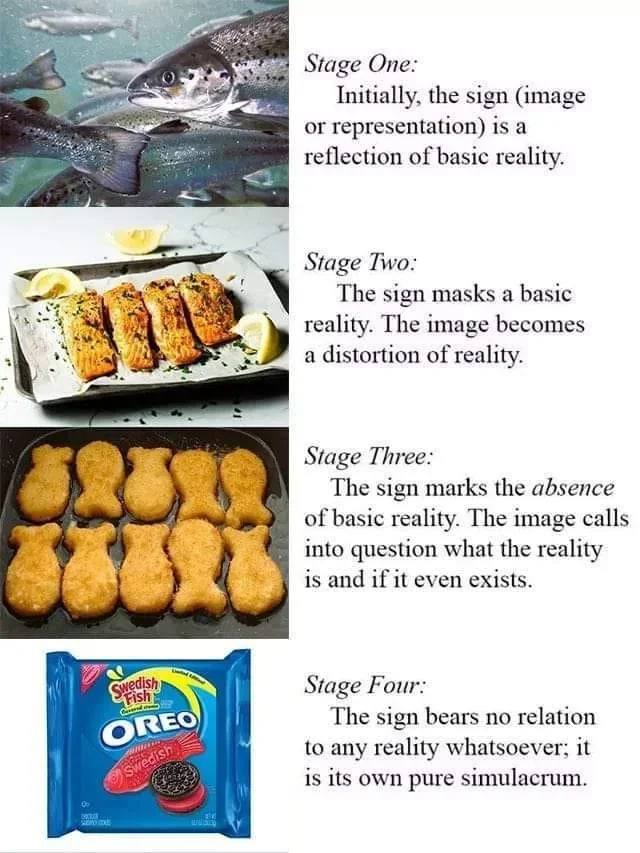

This phenomenon—this total dematerialization of the object into a pure financial instrument—is the "Simulacrum of Luxury" made real. It is the logical and inevitable endpoint of a cultural trajectory described decades ago by the French critical theorist Jean Baudrillard. To understand the LUXUS fund is to understand Baudrillard's "precession of simulacra."

Baudrillard argued that in a consumer society, commodities are valued less for their use-value (their function) or their exchange-value (their monetary cost) and increasingly for their sign-value. Sign-value is the meaning an object conveys—the "style, prestige, luxury, [or] power" it signifies. "Old Luxury" was, from its inception, a system of signs —a "self-referential system of coded signs" —in which value was determined by a brand's ability to "construct symbolic hegemony" (e.g., Chanel's quilting, Hermès' orange).

Baudrillard mapped the journey of the sign through four stages, a "precession" that moves from a reflection of reality to a total detachment from it :

The First Stage: The image is a faithful copy, a "reflection of a profound reality". It is a good, true appearance, a symbol that accurately represents a real thing.

The Second Stage: The image is an unfaithful copy or counterfeit. It "masks and denatures" a profound reality. It is an "evil appearance," a sign that lies about the real.

The Third Stage: The image is a simulacrum. It "masks the absence of a profound reality". The sign no longer points to a "real" thing; it only points to other signs, pretending a reality exists where there is none.

The Fourth Stage: The image is a pure simulacrum. It is the "hyperreal". It is a "copy without an original" that bears "no relation to any reality whatsoever". The simulation precedes and generates the real.

Baudrillard's precession of simulacra provides a critical framework for tracing an object's journey from a reflection of reality (Stage 1) to a "pure simulacrum" with no original (Stage 4).

Financial markets themselves have been analyzed as a "pure simulacrum," a system in which money, "unfettered" from its original "role as a symbol of an underlying thing of value" (like gold), has "taken on a reality of its own." The LUXUS fund is the crash-point where the simulacrum of finance and the simulacrum of luxury merge into one.

The Hermès Birkin bag is the perfect object to trace this tragic four-stage trajectory:

Stage 1: The Original (Reflection of Reality). The original Birkin, famously sketched on an Air France flight for Jane Birkin, was a "reflection of a profound reality". It was designed to solve a real problem: a need for a functional, elegant, durable, and spacious travel bag for a new mother. Its value was rooted in its use.

Stage 2: The Sign (Masking Reality). This is the "Old Luxury" Birkin of the 1990s and 2000s, the era of the infamous "waitlist." This bag masked and denatured its original reality. Its function as a bag became secondary to its new function as a sign of elite status. Its value was no longer in its utility but in its sign-value —its ability to signify that its owner had the wealth, patience, and connections to acquire one.

Stage 3: The Resale Market (Masking the Absence of Reality). This is the Christie’s-era Birkin, the investment-grade objet d'art. This object masks the absence of a profound reality. Its auction price—$165,100 for a Faubourg Birkin 20—has no connection to its material cost, its craft, or even its sign value as a status symbol. Its value is determined by its resale price. It is a simulacrum of the sign —an asset whose value is determined solely by its performance in the secondary market. It has become a self-referential financial loop.

Stage 4: The LUXUS Fund (The Hyperreal). This is the "Bag-Backed Security." It is the pure simulacrum. The LUXUS fund is not selling the bag (Stage 1), the sign (Stage 2), or even the asset (Stage 3). It is selling a financial derivative of the asset—a "share" of the resale price (Stage 3) —which was a simulacrum (Stage 2) of an original object (Stage 1). This is the "copy without an original".

The 43-day, 34% return is hyperreality in its most terrifying form: a financial event so rapid and so detached that it precedes the object's physical existence. The "real" bag, locked in a vault, is just a ghost validating a transaction that occurs entirely in the realm of financial simulation. This is the "Simulacrum of Luxury" made real.

A Crisis of Value: The Objects That Break the Model

The total financialization represented by the LUXUS model is not merely a new chapter in the history of luxury; it is a crisis of value. The model is not just a platform for trading; it is an ideological filter that re-defines value in its own image. A Bag-Backed Security can only function if the bag is as legible, interchangeable, and fungible as a barrel of crude oil or a share of blue-chip stock. This system requires global consensus on an object's worth, based on nothing but brand recognition and resale price.

This is a value monoculture. It can process only one attribute: tradable consensus. By doing so, it actively erases all other forms of value. It cannot see or quantify the human story, craft, and connection that give an object true, lasting meaning. This is the cultural crisis that the financialization model has created, and it is the intellectual and commercial vacuum that our framework, Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA), is designed to fill.

The PLCFA framework is the direct antidote to the Bag-Backed Security. It is not to create products for a market, but to forge artifacts for a life. It champions the "un-smooth" object, which is defined not by its liquidity but by its narrative, imperfection, and haptic resistance. Where the financial model demands an alienable commodity that can be flipped in 43 days, the PLCFA framework seeks the inalienable possession—an object so embedded with narrative and meaning that it becomes "priceless", the very antithesis of a liquid asset.

The LUXUS model, by its very nature, is structurally incapable of seeing these objects. Its algorithm would register them as having zero or, in some cases, a negative value. To demonstrate this crisis, we must analyze the objects that break the model—perfect examples of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art whose worth is non-transferable, narrative-driven, and fundamentally hostile to financialization.

The 'Un-Smooth' Object I: Rei Kawakubo and the Value of Critique

The first object that reveals the bankruptcy of the financialization model is Rei Kawakubo's Spring/Summer 1997 collection for Comme des Garçons, "Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body," known by the press as "Lumps and Bumps". This collection is a perfect "un-smooth" object, an artifact whose value derives not from aesthetic desirability but from its intellectual critique.

The collection consisted of stretch polyester garments, many in a simple gingham pattern, that were internally padded with lumpy rolls. These pads were placed unconventionally on the abdomen, hips, back, and shoulder region, deliberately distorting and reshaping the female form. This was not an act of beautification; it was an act of Critical Fashion Practice, a garment that announces a level of conceptual functionality that exceeds the capacity of simple clothing.

The narrative value of the collection was its profound and challenging critique of patriarchal beauty standards. Academics like Francesca Granata have noted that the collection manifests the relation between the pregnant body, the female body, and the disabled body. It was an exploration of the grotesque and the non-fit body, forcing the viewer to challenge precepts about the world. Kawakubo's work is known for being driven by ideas and for telling a story of rebellion and innovation.

Rei Kawakubo's 1997 "Lumps and Bumps" collection: a perfect "un-smooth" object whose value lies in its intellectual critique of beauty standards, making it hostile to financialization.

This object is the definition of anti-liquidity. Upon its debut, the collection sparked controversy. The fashion press, baffled and disturbed, compared the pads to tumors. This, for Kawakubo, was the validation of the work. As she famously stated, You can tell if it's a good collection if people are afraid of it. The value of this dress is non-transferable; it is not a status symbol to be flipped, but an idea to be contended with.

Now, apply the LUXUS model. A fund manager seeking a 34% return in 43 days requires an asset of immediate, universal, and consensual desirability. The "Lumps and Bumps" dress was designed to be undesirable, to frighten and challenge conventional notions of beauty. Its value is intellectual and conceptual, not aesthetic or financial.

Therefore, you cannot securitize a critique. You cannot flip a "tumor" dress. The LUXUS model would assign this dress a value of zero, or even negative, as it actively repels the consensus mechanism required for liquidity. Its value cannot be transferred in a 43-day window because it needs time: time for intellectual engagement, time for the narrative to build, time for the controversy to resolve into its current iconic status. This object is fundamentally illiquid and exists in a realm of value that the financialization model cannot even perceive.

The 'Un-Smooth' Object II: Carol Christian Poell and the Aesthetics of Endurance

The second — and perhaps more potent — refutation of the Bag-Backed Security is the work of Austrian designer Carol Christian Poell, specifically his Object Dyed, No Seam Drip-Rubber sneakers. This object is the ultimate example of the "Aesthetics of Endurance," a core tenet of the PLCFA framework. Its value is not static, tradable, or transferable; the owner must earn it through the process of its own destruction.

The CCP Drip Sneaker is an artisanal masterpiece, handcrafted from materials like kangaroo leather. It undergoes an object-dyed process, in which the entire finished sneaker is dyed at once, imparting individual character to each piece. Finally, the shoe is dipped in latex, which dries by gravity, creating asymmetrical stalactites of material, or drips, from the sole. These drips are the object's most defining and most ephemeral feature.

The entire beauty of these shoes, as their adherents will attest, is that the drips are designed to be destroyed. They are not permanent. The design brief is one of impermanence. Over time, walking on these will erode the rubber and eventually fade the spikes away. The drips will ultimately wear off.

The CCP Drip Sneaker, an example of the "Aesthetics of Endurance." Its conceptual value is unlocked only by destroying its financial value (the drips) through wear.

This object is a conceptual trap for the financialization model. Recall the fractional model's promise: to remove the hassles out of ownership by placing the pristine asset in a Bank Vault. The CCP sneaker is the hassle. Its entire conceptual purpose is to be worn down and, in doing so, to make them their own. The owner faces a profound choice: they can preserve the sneaker as a 3D art object, protecting its resale value by keeping it pristine. Or, they can wear the sneaker, destroy the drips, and in doing so, unlock its conceptual value, fulfilling the artist's intent.

This is the "Aesthetics of Endurance." The value is not transferred at purchase; it is created by the owner's commitment to the object's life and, in this case, its death.

This object is the nemesis of the Bag-Backed Security. Its financial value and its conceptual value are in direct, inverse correlation. The more you wear the sneaker (increasing its conceptual and narrative value), the less it is worth on the secondary market (decreasing its financial value). The LUXUS model, which requires a pristine, vaulted asset to secure its 34% flip, is rendered impotent. To "preserve" the Drip Sneaker as an asset is to undermine its purpose fundamentally.

This object cannot be securitized. It is the ultimate "un-smooth" object. It proves that true value can be at odds with price. It forces a choice that the world of "Old Luxury" can no longer answer: are you an investor, or are you a steward?

From Financialization to Stewardship—The PLCFA Framework

We stand at the terminus of "Old Luxury." Its logic, predicated on "sign-value", has been pursued to its hyperreal conclusion. The emergence of the LUXUS fund and its Bag-Backed Securities is the final, absurd, and inevitable phase. We have witnessed the destruction of economic value in favor of another type of value, a value that has now, finally, completely detached itself from the object. The simulation of value—the 34% return on a 43-day flip—is now more real and more profitable than the object's underlying, material worth. This is the "Simulacrum of Luxury" made real, a "self-referential system of coded signs" trading on its own abstraction in a closed loop.

This report has demonstrated that this system of total financialization is not just a new market; it is a crisis of value. It is a value monoculture that, by its very design, is incapable of processing "un-smooth" objects. It cannot see the intellectual critique of a Rei Kawakubo Lumps and Bumps dress, dismissing it as an illiquid, undesirable liability. It cannot comprehend the earned endurance of a Carol Christian Poell Drip Sneaker, as its value is inversely correlated with the very "pristine condition" the financial model demands.

This total dematerialization creates an intellectual and commercial void. This is the cultural crisis that our framework, Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA), is designed to answer.

PLCFA is the cure for the sickness of hyperreality. It is a material antidote that re-anchors value in the real world. Where the LUXUS model offers ownership of an alienable commodity, PLCFA demands active stewardship of an inalienable possession. Where financialization demands the smooth, liquid, and fungible asset, PLCFA champions the "un-smooth" object—the narrative, imperfection, and haptic resistance that makes an artifact unique and, therefore, priceless. Where the Bag-Backed Security erases the object's story to maximize its tradability, PLCFA restores the idea of value by prioritizing "emotional durability" and "garments with stories." The LUXUS model offers its accredited investors a share in a ticker symbol, collateralized by a ghost in a vault. The PLCFA framework offers the individual the mantle of stewardship of an artifact. One is a bet on pure, abstract price. The other is an investment in a well-considered life. This is the definitive choice we now face: a future of total simulation, or a return to the object of affection.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.