THE SHADOW OF THE LOOM: Semiotic Enclosure, Racial Capitalism, and the Architecture of Post-Luxury Reparation

The global luxury apparatus currently stands at a precipice defined by a second great detachment. The first, articulated in the foundational texts of Marxist political economy, was the alienation of the worker from the product of their labor—a severance that fueled the industrial capitalism of the 19th and 20th centuries. The second detachment, a phenomenon specific to the financialized and digitized economies of the 21st century, is the alienation of the cultural signifier from its ancestral origin. This severance is not merely a matter of art-historical attribution; it is the central engine of value creation for a luxury sector that, by its own admission, has fully dematerialized the object into a financial abstraction. This study investigates the structural, historical, and economic relationships between the iconic design motifs of the European luxury oligopoly and the traditional symbolic systems of the Global South.

We inhabit an era of the hyperreal, where the logo is no longer a guarantor of quality or heritage, but a free-floating signifier that commands capital through the simulation of prestige. The luxury object has become a simulacrum—a copy without an original, or more accurately, a copy that has murdered its original to usurp its place in the hierarchy of value. This report posits that the multi-billion-dollar valuation of European heritage brands is partially derived from the uncompensated enclosure of aesthetic commons—what we term "semiotic primitive accumulation." This mechanism is not the behavior of a single bad actor but the operating system of the entire industry. From the textile archives of the Kuba Kingdom to the embroidery workshops of Oaxaca, from the mountains of Romania to the hills of Laos, the luxury sector draws aesthetic vitality from source communities to fuel valuation by European holding companies.

The familiar imbalance identified in our research directive, ancestral designs generating billions while their originating cultures remain uncompensated, is not an accidental byproduct of globalization. Rather, it is the result of a deliberate, century-long process of erasure. Through the lenses of Racial Capitalism and the dark matter thesis of the art world, this study argues that the transition to the Post-Luxury era requires abandoning Aspirational Sovereignty—the brand as the sole dictator of taste and value, in favor of Reparative Stewardship. True luxury in the coming decade cannot be defined by the material exclusivity of the object, nor the financial exclusivity of the ticker symbol, but by the ethical depth of its provenance. We must move from an economy of Appropriation to an economy of Fractional Repatriation.

The Theoretical Apparatus: Racial Capitalism and the Colonial Archive

To navigate the complex terrain of luxury extraction, we must first establish a rigorous theoretical lexicon. The foundation of our analysis is the concept of Racial Capitalism, a term popularized by Cedric Robinson to describe the inextricable link between the development of capitalism and the production of racial difference. Robinson argued that capitalism did not break from the feudal order's racism but rather evolved from it, utilizing the social construction of race to facilitate stable, inequitable distributions of resources. In the context of luxury fashion, race functions as an ordering principle" and an "economy of justice," justifying the extraction of value from racialized bodies and cultures. This manifests as the coloniality of value: the European designer is positioned as the Alchemist who transforms raw material into gold, while the Indigenous artisan is positioned as nature itself, providing the raw material which has no value until it is touched by the European hand.

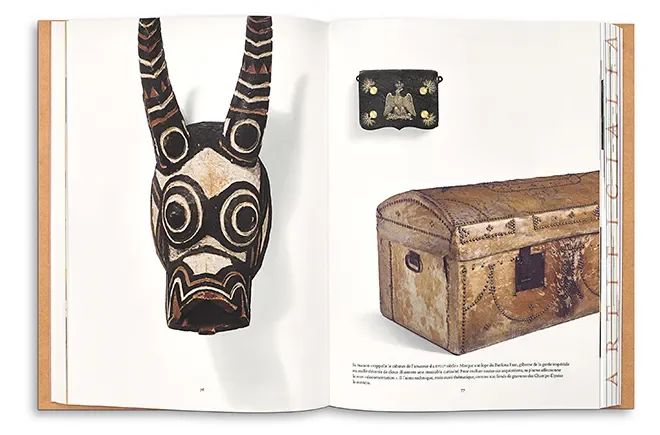

The Colonial Archive: Glass enclosures at the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro, where looted artifacts were reclassified as "primitive art," facilitating the decontextualization required for luxury appropriation.

This extraction is facilitated by the Colonial Archive, physically manifested in institutions such as the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris (founded in 1878). It was here, in the chaotic halls filled with looted artifacts from the French Congo and West Africa, that the European avant-garde discovered modernism. The museum functioned as a mechanism of decontextualization, stripping objects of their specific spiritual and political functions and presenting them as “primitive art”—a category that simultaneously elevated their form and denied their intellectual content. This laundry for stolen meaning allowed artists and designers to appropriate African geometries without engaging with African humanity. The modernist aesthetic—characterized by flatness, abstraction, and repetition—was largely fueled by this appropriation of African aesthetic technologies.

Complementing this is the concept of Artistic Dark Matter. Gregory Sholette argues that the visible art world is supported by a massive, invisible bulk of creative labor excluded from the value chain, yet whose existence stabilizes the system. In our analysis, the geometric traditions of the Global South constitute the "dark matter" of the luxury galaxy. They provide the gravitational pull—the coolness, the mystery, the graphic power—that holds the brand together, yet they remain invisible in the corporate history. Without the primitive intervention that disrupted European naturalism, the modern luxury logo would not exist. Suppressing this lineage is necessary to maintain the brightness of the European star.

Case Study I: The Geometry of Erasure (The Louis Vuitton Paradigm)

The legitimacy of the luxury house rests on its Origin Myth. For Louis Vuitton, this myth centers on the invention of the Damier (1888) and Monogram (1896) canvases as acts of singular European genius. However, a forensic analysis reveals that these innovations occurred in the epicenter of the colonial encounter, at the precise moment when the loot of empire was flooding Paris.

The Kuba Kingdom, located in the Kasai region of the current Democratic Republic of the Congo, is world-renowned for its textile arts, particularly the raffia velvets produced by the Shoowa people. Historical precedence establishes that Kuba weaving traditions and their defining "rectilinear labyrinth" designs were developed as early as the 17th century, fully two centuries before the birth of Louis Vuitton. The Kuba aesthetic is governed by a complex cosmology where the checkerboard pattern represents the order of the universe and the duality of existence. Unlike the rigid Euclidean grid of the European tradition, Kuba designs often employ "artistic fractals" and "off-beat phrasing," where the pattern begins with regularity but breaks into improvisational variation to signify the dynamism of life.

The Ancestral "Source Code": This 20th-century Kuba Shoowa textile (Ref. 0869) demonstrates the complex, hand-embroidered geometric patterns that predated and likely influenced iconic European luxury motifs.

The visual resonance between the Kuba checkerboard and the Louis Vuitton Damier canvas is undeniable and, to the critical eye, "uncanny". The Damier, registered in 1888, appears as a "rationalized" enclosure of the African form—stripping away the rhythmic complexity and the "dangerous" crossing points of the Shoowa textile to suit the needs of industrial mass production. This is not merely a stylistic coincidence. We must recall that Georges Vuitton was deeply involved in the Colonial Exhibitions of his time, designing the Louis Vuitton pavilion for the 1931 Colonial Exposition, which explicitly displayed ivory and "exotic" goods alongside trunks, physically situating the brand within the colonial trophy cabinet. a strategy of commodified spectacle that our study of the Murakami collaboration critiques. The Damier thus functions as a geometric enclosure: the capture of a wild, cosmological signifier and its imprisonment within the grid of the trademark.

The Architect of Extraction: A page from Cabinet of Wonders displaying a tribal mask from Gaston-Louis Vuitton’s personal collection alongside an LV trunk, illustrating the literal integration of colonial artifacts into the brand's design language.

If the Damier represents the enclosure of geometry, the Monogram represents the enclosure of language. In the Cross River region spanning Nigeria and Cameroon, the Ekpe secret society developed Nsibidi, a system of graphic communication. Unlike decorative motifs, Nsibidi is a script; its symbols—circles, crosses, and interlocking loops—convey concepts of love, unity, judgment, and danger. The "quatrefoil" shape and the "concave diamond" found in the Louis Vuitton Monogram bear a striking structural likeness to specific Nsibidi characters often depicted on ukara cloth, a textile reserved for high-ranking initiates.

The Semiotics of Power: Much like the Nsibidi script, Adinkra symbols represent a sophisticated system of African graphic communication where specific geometries carry profound judicial, social, and spiritual weight.

When Georges Vuitton introduced the Monogram in 1896, the official narrative cited "Japonisme" and medieval heraldry as sources of inspiration. This explanation effectively sanitizes the brand's history, aligning it with "high" civilizations while erasing the "primitive" influences that were permeating Paris at the time. By reducing the Nsibidi script—a tool of legislative and judicial power —to a mere "floral ornament," the luxury apparatus commits a form of epistemicide. The "cruel letters" of the Ekpe society, which once held the power of life and death, are defanged and repurposed to signal nothing more than consumer capacity. As noted in our critique of the hyperreal spectacle, the dominant culture does not merely repress the other; it devours it, digesting its symbols until they are void of their original political content.

The Political Economy of the Pattern: Value Extraction

The aesthetic similarity is merely the surface of the issue; the deeper pathology is economic. We must quantify the disparity between the value generated by the "appropriated" design and the value retained by the "originating" culture. This disparity is the engine of what Cedric Robinson defined as Racial Capitalism—a system that relies on the "social production of difference" to justify extraction. In the context of luxury fashion, this manifests as the "coloniality of value," where the European designer is the alchemist who transforms raw material into gold, while the African artisan is merely part of the landscape.

The Financialization of the "Icon" vs. The Poverty of the Origin

LVMH, the world's largest luxury conglomerate, reported revenue of €84.7 billion in 2024, with its Fashion & Leather Goods division driving nearly half of that volume. This revenue is heavily dependent on the "Pattern Premium"—the value added by the Damier or Monogram to a product that is otherwise comprised of industrial materials. A standard coated canvas bag, often critiqued as glorified plastic, has an estimated production cost of approximately $170 yet retails for over $1,700. The markup is entirely semiotic; the consumer pays for the myth, not the material.

Contrast this with the economic reality of the producers of the "source code." Antique Kuba Shoowa panels, widely recognized by scholars as masterpieces of textile art, sell at major international auctions for prices ranging from a mere $120 to $200. This represents a profound inversion of value: a mass-produced, vinyl-coated simulacrum is valued by the market at ten times the price of the unique, hand-crafted, culturally sacred original. This valuation confirms the Artistic Dark Matter thesis: the visible "star" system of the luxury world is supported by a massive, invisible bulk of creative labor from the Global South, which provides the gravitational pull of "coolness" but remains excluded from the value chain.

The "Useful Article" Doctrine: The Legal Architecture of Erasure

LVMH, the world's largest luxury conglomerate, reported revenue of €84.7 billion in 2024, with its Fashion & Leather Goods division driving nearly half of that volume. This revenue is heavily dependent on the "Pattern Premium"—the value added by the Damier or Monogram to a product that is otherwise comprised of industrial materials. A standard coated canvas bag, often critiqued as glorified plastic, has an estimated production cost of approximately $170 yet retails for over $1,700. The markup is entirely semiotic; the consumer pays for the myth, not the material.

Contrast this with the economic reality of the producers of the "source code." Antique Kuba Shoowa panels, widely recognized by scholars as masterpieces of textile art, sell at major international auctions for prices ranging from a mere $120 to $200. This represents a profound inversion of value: a mass-produced, vinyl-coated simulacrum is valued by the market at ten times the price of the unique, hand-crafted, culturally sacred original. This valuation confirms the Artistic Dark Matter thesis: the visible "star" system of the luxury world is supported by a massive, invisible bulk of creative labor from the Global South, which provides the gravitational pull of "coolness" but remains excluded from the value chain.

Case Study II: The Archipelago of Extraction (A Global Survey

The mechanism of "semiotic enclosure" observed in Louis Vuitton is replicated across the luxury landscape. The industry operates as an archipelago of extraction, where brands act as colonial governors, harvesting "raw" aesthetic data from the periphery to refine into "high" fashion.

The Balkan Enclosure came to light in 2017 when Christian Dior released a pre-fall collection featuring a shearling coat that was a near-exact replica of the traditional cojoc jacket worn by the people of Bihor, Romania. The economic disparity was grotesque: Dior sold its version for €30,000, while the authentic Bihor jacket sold for approximately €500. This "Value Inversion" values the industrial copy at 60 times the price of the handcrafted original, a symptom of the hollowing out of luster, as Dana Thomas diagnoses.

Latin American Extraction is visible in the work of Isabel Marant and Carolina Herrera. In 2015, Marant released a blouse visually identical to the traditional Tlahuitoltepec blouse of the Mixe people. Marant's defense was that the design was in the "public domain," effectively arguing that because the Mixe people had not patented their ancestral heritage, it was free for the taking. Herrera's Resort 2020 collection featured embroidery motifs taken directly from the Tenango de Doria community, which the brand dismissed as a "tribute" while selling dresses for thousands of dollars.

The Digital Enclosure seen in Max Mara's interaction with the Oma people of Laos reveals the technological evolution of this extraction. Max Mara digitally scanned the Oma's vibrant appliqué embroidery and printed it onto fabric, reducing a tactile, labor-intensive craft to a 2D industrial print. This is the ultimate dematerialization: the texture of the labor is removed, leaving only the ghost of the image.

The Commodification of the Sacred and the Fashion Colonialism of Print round out this survey. Gucci’s "Indy Full Turban" commodified the Sikh dastaar, stripping the object of its religious weight to render it palatable for the white consumer. Meanwhile, Stella McCartney and Loewe have faced backlash for using "Ankara" prints and Otavalo weaving patterns without initial credit, profiting from Indigenous aesthetics while selling accessories for over $2,000.

The Sacred Intermediary: A Kwele Ekuk mask. Its "rationalized" geometry has been cited as a direct aesthetic precursor to modernist abstraction and, more recently, as a source for iconic luxury monograms.

The Post-Luxury Paradigm: A Reparative Thesis

The "familiar imbalance" of billions versus pennies is not an aberration of the legal system; it is its intended result. International Intellectual Property (IP) law functions as a tool of neocolonial enclosure. The primary mechanism of this dispossession is the "Useful Article" doctrine. Clothing is considered a "useful article," and thus its design is generally excluded from copyright protection unless the artistic features can be "conceptually separated" from the utility. This creates the relentless pace that kills creativity in the fashion calendar.

This doctrine creates a trap for Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs). Indigenous designs are viewed under Western law as functional or communal and thus fall into the Public Domain. The concept of the Public Domain acts in this context as terra nullius—nobody's land. It declares that the cultural assets of the Global South are free for the taking. However, when a luxury brand "discovers" this motif and registers it as a Trademark, they effectively privatize the commons. The Mixe people cannot own their blouse design because it is too old, but a corporation can trademark its distinctive interpretation.

The transition to the Post-Luxury era requires abandoning Aspirational Sovereignty in favor of Reparative Stewardship. We propose implementing Fractional Repatriation using the very technologies that currently drive financialization: the blockchain and smart contracts. Just as the market now speculates on ultra-contemporary art, we can utilize this infrastructure to assign heritage equity to source communities.

Living Heritage: The Maasai shuka and beadwork are a visual language of identity and status, once unceremoniously appropriated by luxury brands but now protected by the Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative (MIPI).

Imagine a Post-Luxury object encoded with a smart contract that automatically routes a percentage of its initial sale—and, crucially, a royalty from every subsequent resale on the secondary market—back to a sovereign trust managed by the originating artisan guild. This would transform the relationship from one of theft to one of licensing, ensuring that the dark matter of the art world is finally illuminated and compensated. If the Damier is a derivative of the Kuba cosmology, then the Kuba Kingdom holds a moral equity stake in that derivative. Technology now allows us to convert that moral stake into a financial one.

The Economics of Extraction: A Study in Inequality

The theoretical and legal frameworks result in a material reality defined by grotesque inequality. LVMH, the world's largest luxury conglomerate, reported revenue of €84.7 billion in 2024. This revenue is heavily dependent on the Pattern Premium—the value added by the appropriated motif to a product often made of industrial materials, such as coated canvas. A standard bag has an estimated production cost of approximately $170, yet retails for over $1,700. The markup is entirely semiotic, a dynamic intensified by trade wars and market reshaping.

Contrast this with the economic realities of the source code producers. Antique Kuba Shoowa panels sell at auction for $120 to $200, while hand-embroidered Tenango table runners sell for roughly $85-$200. This represents a profound inversion of value: the market values the mass-produced, vinyl-coated simulacrum at ten to twenty times the price of the handcrafted, culturally sacred original. This pricing structure confirms that the luxury star system extracts the vitality of the "primitive" form while discarding the maker's humanity and economic viability.

The Post-Luxury Paradigm: From Extraction to Reparation

Based on this analysis, the Objects of Affection Collection proposes a definitive pivot from consumer aspiration to institutional reparation. We must move beyond the critique of appropriation toward a model of structural reparation. This requires adopting Reparative Stewardship, in which brands pay a Heritage Dividend for the use of Traditional Cultural Expressions.

Proto-models of change are emerging. Faherty has implemented a Native Partnership Program, and Osklen sources materials directly from Amazonian communities. Even Hermès has engaged in fee-based collaborations with Oaxacan artisans. These examples demonstrate that commercial success is compatible with ethical sourcing. However, the most radical proposal is the use of computational textile technology and blockchain to enforce Fractional Repatriation. By tokenizing luxury objects, we can embed Smart Contracts that automatically route a royalty from every sale back to a trust managed by the source community.

The End of the Innocent Object

The luxury handbag is not an innocent object. It is a palimpsest, a layered document of history where the glossy varnish of Parisian finance obscures the Shadow of the Loom. For the Objects of Affection Collection, the mission is clear. We must function not merely as a fine art program, but as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the world of objects.

By revealing the semiotic enclosure that underpins the luxury economy, we clear the ground for a new architecture of value. The future of luxury does not lie in the accumulation of dead symbols, but in the cultivation of grace and the stewardship of living histories. The "Object of Affection" in 2026 is one that acknowledges its debt, pays its rent, and heals the wound of its making.

Further Inquiry & Audio Documentation

For a deeper forensic analysis of the Geometry of Erasure and the economic mechanics of Semiotic Primitive Accumulation, we invite you to listen to the accompanying audio briefing. This session provides a step-by-step breakdown of the "Value Inversion" and the proposed architecture for Fractional Repatriation.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.