The Narrative as the Original: AI, Simulation, and the Custodial Strategy of PLCFA

A visual representation of the study's core tension. On the left, the "Curated Algorithm"—a 'smooth,' ephemeral, and infinitely reproducible digital display. On the right, the "One Original"—a singular, 'un-smooth,' and physically permanent sculpture that serves as a tangible anchor of meaning.

The cultural and technological landscape of the 21st century is currently defined by a profound existential panic. The rapid proliferation of Generative Artificial Intelligence—algorithmic systems capable of producing novel, complex, and often aesthetically sophisticated content on demand—has triggered a deep ideological divide and widespread anxiety. This is not merely a technical disruption; it is a philosophical crisis. Across creative industries, the debate intensifies, fueled by legitimate concerns over the "authenticity and emotional depth" of machine-made art and design. Artists, writers, and musicians voice fears of an emergent technology that threatens to sever the fundamental human connection between a creator and their audience, challenging traditional notions of creativity, originality, and authorship. This discourse is dominated by a sense of loss, a fear that the "traces of an artist's interiority" are being replaced by a "superb mimic".

This study argues that this perceived crisis is not, in fact, new. It is, rather, the logical and ultimate endpoint of a cultural trajectory that has been accelerating for over a century. The anxiety surrounding Generative AI is a displaced panic. Its true source is not that machines can create, but that we, as a culture, have progressively untethered value from any stable anchor. The "state of exhaustion" previously identified within the traditional luxury market—a system hollowed out by its own "Scarcity Paradox" and the replacement of tangible utility with the abstract "sign-value" of a logo—is the direct antecedent to the AI crisis. Both are symptoms of the same condition: a deep cultural exhaustion with value systems based on aesthetics and simulation alone. The AI-generated image and the mass-produced luxury handbag are philosophically identical; they are manifestations of what the theorist Jean Baudrillard defined as the "simulacrum," a copy detached from any original, material, or functional reality.

Generative AI, in its very ubiquity, does not destroy the concept of originality. Instead, it acts as a powerful and necessary clarifying agent. It forces a bifurcation of our material culture, splitting the world of objects into two irreconcilable categories. On one side, we have the infinitely reproducible, frictionless, and passive aesthetic of the algorithm—what the philosopher Byung-Chul Han would call "Smooth". On the other, we find the singular, "Un-smooth," and haptic object defined by its resistance, its physical permanence, and its narrative depth. This second category is the exclusive domain of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA), a framework defined by the core principle that an object's value is derived not from its price or its materials, but from its "inseparability of concept and function" and its capacity to serve as a "tangible anchor of meaning".

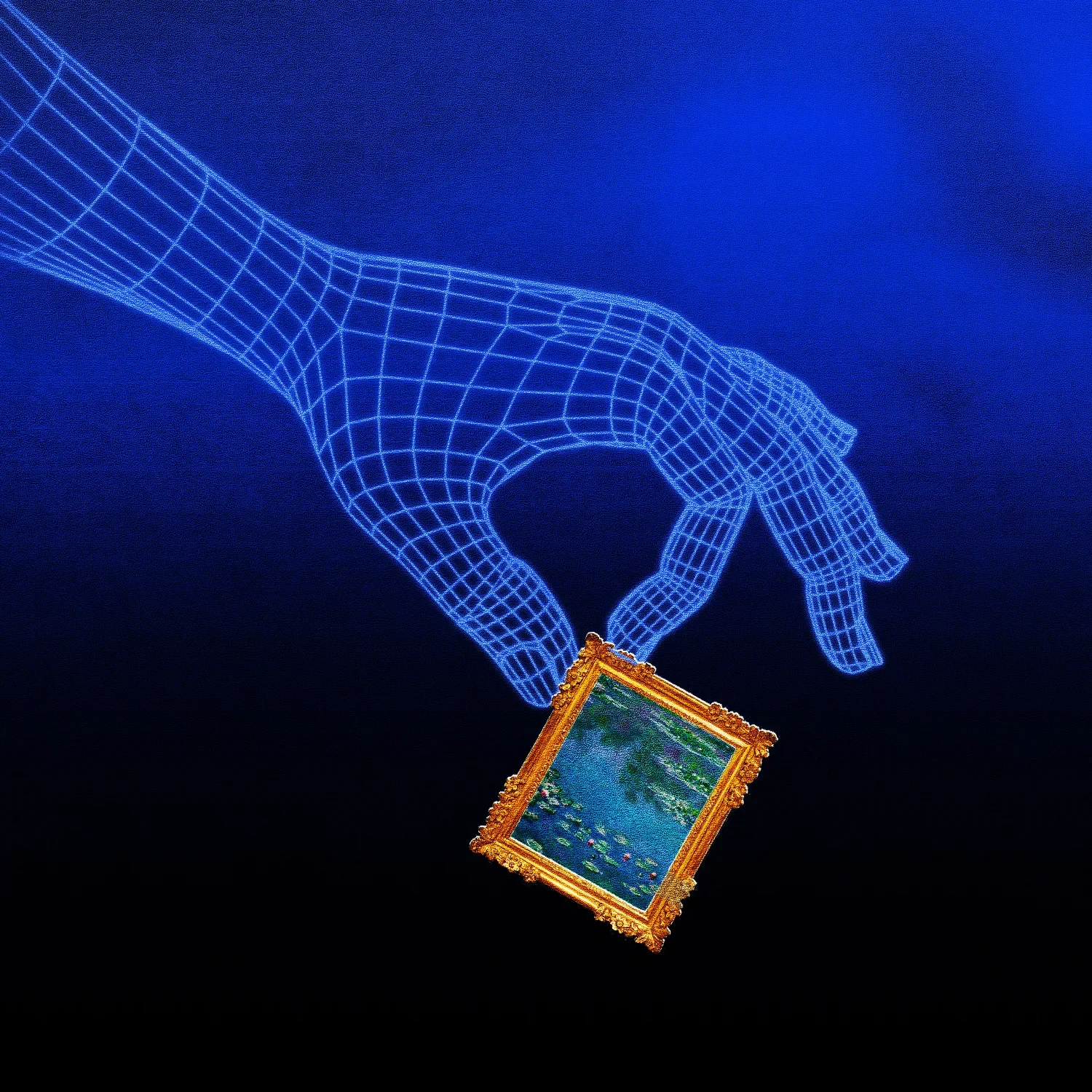

The "simulacrum" in action: both the AI-generated image (left) and the mass-produced luxury handbag (right) represent copies detached from original, material, or functional reality, embodying a deep cultural exhaustion with value systems based on aesthetics alone.

This study is a definitive exploration of this tension. It deconstructs the contemporary AI debate to reveal its philosophical foundations, moving from an analysis of AI as a force of mass reproduction to an investigation of AI as a profound conceptual tool. Ultimately, this report will demonstrate that in a world saturated with algorithmic content, the principles of PLCFA are not just relevant; they have become the last, best defense of authentic human value. AI, far from rendering the "One Original" obsolete, has inadvertently made it more necessary, more potent, and more valuable than ever before. It proves conclusively that in the 21st century, true, durable value no longer resides in the dexterity of the hand, but in the singular, custodial power of the narrative.

Part I: The Simulacrum of Authenticity — AI as the New Mass Luxury

The public and critical apprehension surrounding Generative AI is rooted in a correct, if not always fully articulated, philosophical intuition. The technology, in its current mass-market form, represents the perfection of simulation, capable of producing outputs that are aesthetically pleasing but conceptually vacant. This vacancy is not a flaw in a specific model but a fundamental attribute of the process. The core of the critique is that AI-generated art, as a "superb mimic" , inherently lacks the foundational elements that human beings rely upon to create and ascertain value.

Philosophical critiques emerging from across academia and the arts converge on this point: machine-generated works lack "true insight and experience". They are, by definition, derivative, incapable of possessing what novelist Daphne Kalotay describes as a "genuine vision from living in a specific physical world". An AI model does not experience the world; it does not feel, suffer, or possess a "personality". It can only "regurgitate" statistical composites of the human experiences it has ingested from its training data. The most profound critique, articulated by commentators in The Guardian, is that this process severs the "communion" between creator and viewer. The essence of art, they argue, is not the final product but the human act of imbuing an object with "traces of an artist's interiority," allowing another person to connect with that singular, ineffable experience. An AI, lacking an interior life, cannot participate in this "Symbolic Exchange".

A highly polished, chrome robot stands in a classic art museum gallery, looking forward with glowing blue eyes, while a traditional, gold-framed painting of a landscape hangs on the wall, illustrating AI's inability to emotionally connect with art.

This philosophical emptiness manifests as a specific, dominant aesthetic. The philosopher Byung-Chul Han's critique of digital "smoothness" provides the precise language for this phenomenon. Most AI-generated content is the epitome of the "smooth"—a frictionless, flawless, and passive surface that offers "no resistance" and therefore "no real experience". It is an aesthetic of the Same, perfectly optimized for passive consumption on a screen. It aligns seamlessly with the "commercial genres with easily recognizable styles and tropes" that critics note are most at risk of AI replacement, as these genres are already predicated on simulation rather than originality. This digital "smoothness" is the direct aesthetic counterpart to the conceptually hollow "sign-value" of traditional luxury, which has long been the subject of the PLCFA critique.

This conceptual hollowness is compounded by a deep ethical contamination. The value of any object, within the PLCFA framework, is inextricably linked to its narrative, which includes its ethical provenance. Here, the mass-market AI model fails catastrophically. The dominant critique against these systems is not just that they are mimics, but that they are thieves. The terms "fully automated luxury plagiarism" and "mass theft" have entered the lexicon for a specific reason. The AI models are not built in a vacuum; they are built by "harvesting data from pre-existing works," often "copyrighted work without a licence". This non-consensual "scraping" constitutes an industrial-scale exploitation of artistic labor, using artists' work "without permission or payment to build commercial AI products that compete with them". From a PLCFA perspective, an object born from a foundation of "mass theft" is valueless. Its origin story is not one of human intention and craft, but one of appropriation and exploitation.

This combination of conceptual emptiness and ethical bankruptcy leads to a predictable economic outcome, one that mirrors the decline of traditional luxury. AI art is currently being positioned as the ultimate "mass luxury." On one hand, elite cultural gatekeepers like Christie's are attempting to legitimize AI-generated pieces as a new high-end asset class, scheduling major auctions that command high prices. On the other hand, the technology's primary commercial application is to "democratise luxury-style aesthetics" for mass-market retailers, allowing them to simulate the look of exclusivity and high-end design in virtual stores. This is a perfect, accelerated repetition of the "Scarcity Paradox" that defines the "state of exhaustion" of traditional luxury. An object—or in this case, an aesthetic—is simultaneously marketed as exclusive while being, by its very nature, infinitely reproducible and universally accessible. This strategy does not create value; it hollows it out, leading to the same "price fatigue" and "quiet rebellion" that PLCFA was identified as the antidote to.

Defenders of Generative AI often dismiss these critiques by drawing an analogy to the 19th-century invention of photography. That technology, they note, was also dismissed as a "soul-less" mechanism that would "supersede the art of painting". It was derided for being "mechanical" and lacking the "invention and feeling" of true art, yet it evolved into a legitimate and profound artistic medium. This analogy, however, is fundamentally flawed, and the distinction reveals the true nature of the AI-generated object. A photographer, using a mechanical tool, extracts from reality. Their art is one of selection, timing, and framing a singular, unrepeatable moment in the real, physical world. Generative AI, by contrast, does not capture or engage with reality. It "regurgitates" a statistical composite of its training data—a vast archive of other images. It is, in the purest Baudrillardian sense, a "simulacrum". It is a map that precedes the territory, a copy without an original. Photography is an art of extraction from reality; mass-market generative art is an art of simulation within the hyperreal. This philosophical difference is not technical; it is absolute. And it is this "un-anchored" nature of the AI simulacrum that makes the PLCFA object—as a "tangible anchor of meaning" rooted in physical and conceptual singularity—more vital than ever.

Part II: The Artist as Curated Algorithm — Redefining Creation Beyond the Hand

The failure of mass-market AI art, therefore, is not a failure of technology but a failure of imagination. It is the failure to see that the AI is not the artist. The art is not the final, frictionless image produced. The true art, and the only one that aligns with the rigorous demands of the Post-Luxury paradigm, is the concept. In this new framework, the artist is not a digital laborer but a "Philosophical Architect"—a human curator who wields the algorithm as an instrument. The art object is not the output, but the system that the artist designs and the narrative they construct around it.

This pivot requires a redefinition of "craft." In this new conceptual practice, manual dexterity and traditional skill are supplanted by conceptual ideation. The new "craft" is twofold. First is "prompt engineering," the practice of designing the textual inputs that guide the AI model. This is not a simple act of typing but a "co-creative process" that requires experimentation and a deep understanding of the model's mechanics. But far more important than the prompt is the act of curation. The artist, as the "originator of the idea," is responsible for "making sense of model outputs, iterating on ideas," and, most critically, "curating the final piece" from a sea of infinite possibilities. This act of selection, of imposing a singular human will onto the algorithmic output, is the new locus of creativity. It shifts the entire practice from one of production to one of conceptualization, aligning it perfectly with the "Conceptual" pillar of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art.

Two practitioners exemplify this new paradigm, operating as true "Curated Algorithms." The first is the German artist Mario Klingemann, a pioneer who explicitly defines the AI as his "instrument," not his collaborator. In a precise analogy, he compares the AI to a piano: a complex instrument that allows for new forms of expression, but which is never credited with the performance. The credit belongs to the artist who plays it. Klingemann's stated role is to "recognise these outputs' potential... and contextualize them within his broader artistic vision". His 2018 masterpiece, "Memories of Passersby I," is the ultimate proof of this thesis. The work, an antique cabinet containing a computer system that generates an endless stream of flickering, distorted portraits, was the first "autonomous AI machine" to be sold at a major auction. The art, as Klingemann insists, is not the fleeting portraits on the screen, which are born and die in moments. The art is the machine itself—the code, the system, the concept. The "function" of this PLCFA object is not to be a portrait; its function is to be a perpetual generator of conceptual questions about memory, identity, and machine creativity, perfectly embodying the inseparability of concept and function.

A visual example of the conceptual AI artist as a "Curated Algorithm." Unlike "smooth" AI mimics, artists like Mario Klingemann use AI as an "instrument" to create distorted, flickering, and conceptually-driven portraits. The art is not the final image, but the generative system that questions memory and identity.

The second key practitioner is the Turkish-American media artist Refik Anadol, who operates as a "data painter" at an architectural scale. For Anadol, the art is inextricably bound to his process. He is not a mere user of a generic model; he is an archivist and a curator of memory. His method involves collecting vast, specific datasets—such as 200 years of MoMA's public archive for his "Unsupervised" exhibition, or over a billion images of Antoni Gaudí's work to "let the building dream" at Casa Batlló—and then training a bespoke AI to "dream intentionally" with this data. His stated narrative is to "make the invisible visible," transforming the data of human memory into "digital pigments". The "function" of his massive, immersive installations is purely conceptual and emotional: to allow an audience to experience the "mind" of a machine that is dreaming of human history.

Crucially, Anadol's practice demonstrates how this conceptual approach solves the ethical crisis of "mass theft". While mass-market models are built on non-consensual "scraping" , Anadol's process is one of obsessive and total transparency. He displays "process walls" that explain his algorithms and, most importantly, where the data comes from. His work is not theft; it is a scholarly, archival, and consensual collaboration with an institution (like MoMA) or a specific, public body of data (like nature records). This is not "fully automated luxury plagiarism". It is the creation of a new work where the ethical provenance of the data is a central part of the narrative. This transparency, this "dialogue with culture" , is precisely what elevates his work from a mere algorithmic spectacle into the realm of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art.

The core ethical crisis of mass-market AI: "non-consensual scraping" and "mass theft" of human artists' work. This process, born from appropriation, is philosophically valueless. It stands in direct contrast to the transparent, archival, and consensual methods of conceptual artists like Refik Anadol.

Part III: Narrative Control as the New Authenticity — From Rothko's Strategy to the AI's Declaration

The central argument of this study rests on a synthesis of this new conceptual practice with a foundational theory of the Objects of Affection Collection: "Mark Rothko's Custodial Strategy". This framework provides the essential linchpin for understanding how value and authenticity are constructed in the age of infinite reproduction. The analysis of Rothko posits that his true, ultimate artistic work was not merely the creation of his sublime canvases; it was his "meticulous control over the presentation, interpretation, and legacy of his work". This "custodial act," which rigidly dictated the lighting, grouping, and environment of his paintings, was a form of "conceptual art" in its own right. Rothko was not just a painter; he was a philosophical architect who enforced a specific narrative, ensuring his works would function not as decoration, but as "secular chapels" for "emotional contemplation". This strategy established a core PLCFA principle: the "ability to shape and maintain a story becomes the ultimate luxury".

Mark Rothko's true masterpiece was not just his canvases, but his "Custodial Strategy." By rigidly controlling the environment, lighting, and grouping, he transformed his paintings from mere decoration into "secular chapels" for contemplation, proving that the power to shape the narrative is the ultimate conceptual act.

Generative AI presents the ultimate test of this "Custodial Strategy." A raw image file generated by an AI is, in its native state, infinitely reproducible, context-free, and therefore valueless. It is the epitome of the "smooth" simulacrum. It only gains value—it only becomes authentic—when a human conceptual artist applies a "Custodial Strategy" to it. This strategy is the "Curated Algorithm." The artist performs a series of curatorial acts that imbue the valueless file with a singular narrative. They select the dataset (as Anadol does with MoMA's archive ), build the generative system (as Klingemann does with his machine ), curate the infinite outputs down to a single instance , and, in the final and most critical step, make the public, conceptual declaration that "THIS is the work."

This act of declaration—backed by the artist's name, narrative, transparent process, and intent—is what magically transforms the reproducible file into the "One Original." In this paradigm, "authenticity" is no longer an intrinsic property of the object (i.S., "was it made by a human hand?"). It has become a contextual property of the narrative (i.e., "was it imbued with a singular human concept and declared as such?"). This human declaration is the ultimate form of what Baudrillard called "Symbolic Exchange". It is a "radical attempt to break out of" the hyperreal world of endless, floating copies by creating a "tangible anchor of meaning". The artist does not create this anchor by making the object, but by contextualizing it. This is the absolute, most refined expression of the PLCFA tenet: "Value Derived from Narrative, Not Price".

This framework creates a new and necessary two-tiered class system for all objects: the "Declared" and the "Undeclared." This system, in turn, provides the definitive solution to the "Scarcity Paradox" that plagues both traditional luxury and mass-market AI art. The problem with mass luxury and "democratized" AI aesthetics is their reliance on an illusion of scarcity. The "Custodial Strategy" as applied by a PLCFA artist is not an illusion; it is an enforced and meaningful conceptual scarcity. On Refik Anadol's hard drives, there may exist gigabytes or terabytes of "undeclared" images generated from the Gaudí dataset—all of them "smooth," valueless simulacra. But there is only one "Living Architecture" declared on the facade of Casa Batlló. There is only one "Unsupervised" declared and validated within the institutional context of MoMA.

The value is created by the artist's curatorial declaration and the institutional validation that affirms it. This is a profound shift. It means "authenticity" has finally and fully separated from "physicality." The "One Original" is no longer defined as the singular physical painting or sculpture. The "One Original" is now the singular, declared concept, which is validated by a human narrative and a cultural context. This is a radical but essential evolution of the Post-Luxury thesis, one that moves it definitively beyond the 20th century's obsession with the handmade and into the 21st century's new battleground: the control of meaning.

The Enduring Primacy of the "One Original"

This study began with the central tension of our age: "The Curated Algorithm vs. The One Original." The analysis concludes that this is not a conflict, but a co-dependent relationship. The "Curated Algorithm," when wielded by a conceptual artist, is the new method for creating and anointing the "One Original." The artist's custodial declaration of a single instance from an infinite series is the new act of creation.

The rise of Generative AI, far from devaluing the thesis of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art, is the single greatest catalyst for it. The relentless saturation of our visual culture with "smooth" , ephemeral, ethically compromised , and emotionally vacant algorithmic images does not satisfy a cultural need; it creates a profound and desperate cultural hunger for its precise opposite. This opposite is the PLCFA object—an object that is "un-smooth" , haptic, and physically permanent. An object defined by its resistance, its imperfections, and an "inseparability of concept and function" that anchors it in the real world.

The future of art, design, and luxury is now clearly and irrevocably forked into two distinct paths:

The Path of the Simulacrum: This is the world of frictionless, "smooth," AI-generated "mass luxury." It is the domain of endless, valueless reproduction, a technological acceleration of the "hollowed out" state of traditional luxury and its "Scarcity Paradox". It is a world of aesthetics without meaning, of signs without referents.

The Path of the PLCFA: This is the world of the "One Original." This path now explicitly includes two types of objects: the physically singular object—such as a Robert Ebendorf jewel crafted from discarded detritus, its value derived entirely from its material story—and the conceptually singular declaration, such as a Refik Anadol installation, its value derived from its custodial narrative and institutional context.

The Objects of Affection Collection exists as the definitive archive and critical lens for this second path. In an age where literally anything can be produced by a machine in seconds, the only remaining, durable human value is the meaning we choose to curate, declare, and steward. The PLCFA object, whether a physical piece defined by its material story or a digital work defined by its "Custodial Strategy" , is not just an alternative to the world of AI. It is the antidote. It is the tangible, resonant proof that enduring value lies not in what is made, but in what is meant.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.