The Custodian's Contract: From Institutional Critique to Systemic Stewardship

The advanced art institution today operates within a profound crisis of purpose. While fiscally stable and often overflowing with historical self-awareness, the museum appears structurally sound but spiritually hollowed-out. The defining mode of engagement for nearly half a century—Institutional Critique (IC)—has reached a state of exhaustion, having been fully absorbed and neutralized by the very entities it targeted. This absorption has resulted in a critical void: the art institution is no longer productively opposed, nor does its self-critique constitute genuine political risk. If the museum cannot find its telos in conflict or passive archiving, it must locate it in a new form of structural commitment.

This study argues that the crisis requires a definitive evolutionary shift, pivoting the institution from passive reflection to active stewardship. The necessary successor framework is the "Custodian’s Contract." This formal, binding, and comprehensive agreement is prescribed as the definitive institutional response to the ontological demands of the emergent practice of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA). The PLCFA artifact, defined by its complex "phygital" nature, actively resists the "smooth" institutional model. The adoption of the Custodian’s Contract thus becomes the mechanism by which the museum graduates from passively performing critique to actively practicing custodianship, re-defining its fundamental identity from a cultural "Mirror" reflecting neutralized anxieties to the foundational "Mass" that provides structural anchor for authentic value.

The contemporary art institution, while structurally sound, often functions as a spiritually hollowed-out space. Its absorption of critique has left a void, demanding a new purpose beyond passive archiving.

Part I: The Smooth Museum and the Eclipse of Friction

1.1 The Legacy of Friction: The Original Power of Opposition

Institutional Critique, as practiced by pioneers in the late 1960s and 1970s, derived its essential power from its adversarial relationship with the museum establishment. Practitioners such as Hans Haacke and Andrea Fraser recognized that the art institution, like the university or public archive, was advanced by Enlightenment philosophy with a promise: the aesthetic process, realized through salons and museums, was coupled with the production of a public subject and public exchange. Institutional Critique revisited that radical promise by confronting the art world with its own socio-political realities.

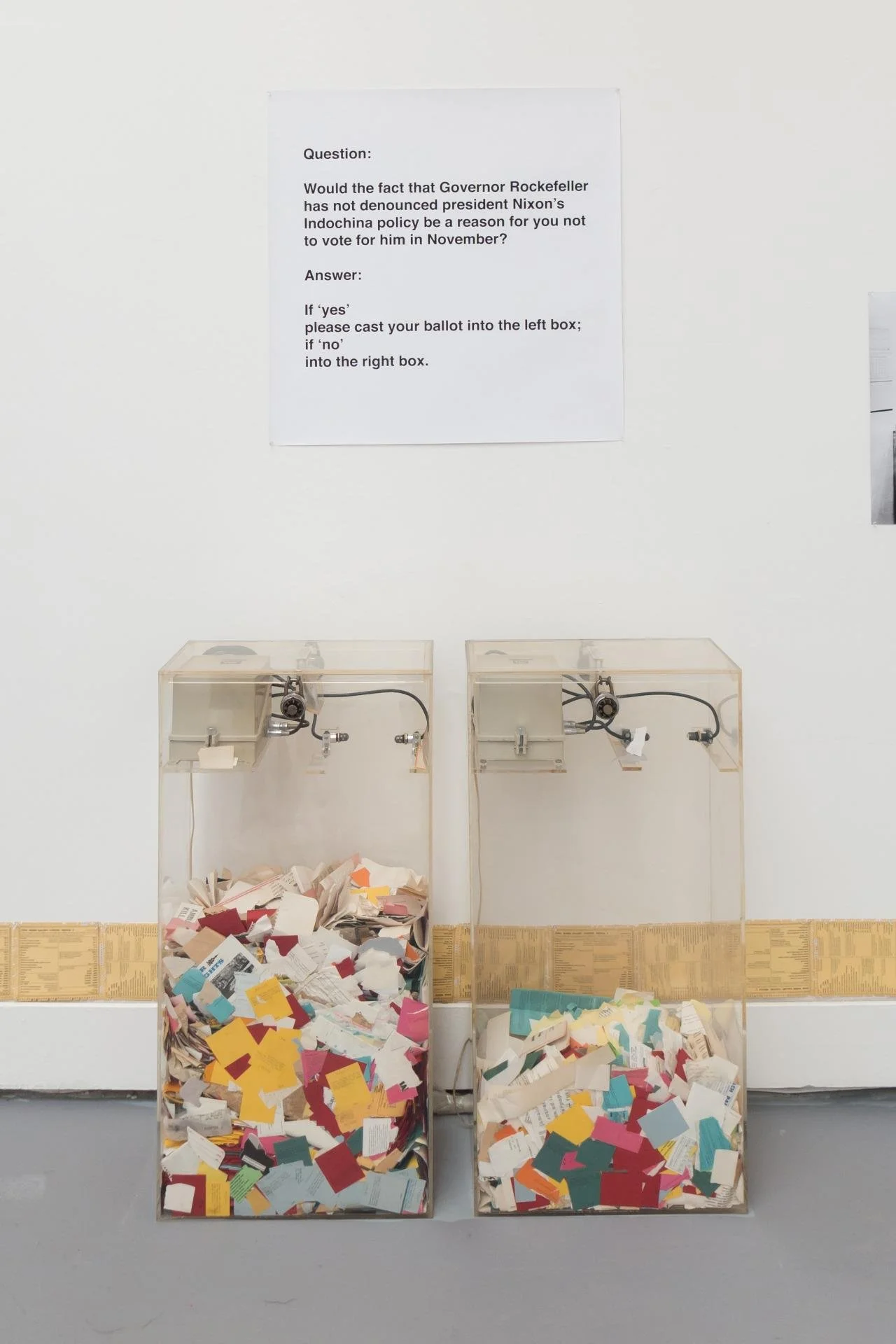

Hans Haacke’s methodology, in particular, involved exposing the political and economic networks underpinning cultural production. His work utilized "symbolic machines that function like snares and make the public act," forcing transparency onto structures of power that preferred to remain opaque. Likewise, Andrea Fraser’s early work was instrumental in shaking and eroding the established foundations of the museum, successfully broadening the parameters of what could be called art. This critical practice was defined by its oppositional stance; it created productive friction that was essential for progressive cultural evolution.

Hans Haacke's 1970 'MoMA Poll' exemplifies early Institutional Critique, directly exposing political and economic networks by asking museum-goers about their voting intentions, creating essential productive friction.

1.2 The Absorption Strategy: Critique as Brand Identity

That productive friction is now, demonstrably, gone. The institutions targeted by IC successfully assimilated the methodology. This neutralization process is often referred to as "New Institutionalism," where the art museum internalizes the critique previously levied against it and enacts a form of self-critique. The museum now readily commissions its own critique and showcases its self-awareness as a form of moral sophistication.

Art theorists have noted that this internalisation is not a political defeat for the institution, but a biological triumph. Institutional Critique, once operating like a destabilizing bacteria, only temporarily weakened the patient—the institution—but ultimately strengthened its immune system in the long run. By appropriating the language and tactics of opposition, the institution transformed potential conflict into content, draining the practice of political effectiveness. Critique became a sophisticated performance, a necessary part of the museum's overall brand identity, validating its progressive credentials without necessitating substantive structural risk.

The co-option of Institutional Critique is not merely a political failure but rather a subtle victory of neoliberal aesthetic optimization. Philosopher Byung-Chul Han posits that neoliberal society, characterized by the pressure of the "achievement society," produces an "aesthetics of the smooth". Smoothness, exemplified in art by the perfect, optimized surfaces of Jeff Koons' Balloon Dogs, is the signature of the present time—without depth or shallows. When the institution internalizes critique, it polishes the hard edges of opposition into a frictionless performance. This performance of ethical awareness becomes a logo, a “smooth” component of the museum’s operational optimization, proving its self-reflexivity while maintaining total systemic control. The friction that once catalyzed change has been engineered out of the system.

Jeff Koons' 'Balloon Dog' exemplifies the "aesthetics of the smooth" – optimized surfaces that signify neoliberal aesthetic triumph. Its presence within a historic palace like Versailles showcases how institutions absorb and present such works, turning potential friction into polished content.

1.3 The Aesthetics of the Smooth and the Hall of Mirrors (Baudrillard)

This successful removal of friction pushes the institution into a profound state of simulation. When the museum’s primary advanced practice is a performance of self-critique that demands no genuine structural overhaul, it enters the realm of the Baudrillardian simulacrum. Jean Baudrillard argued that in the post-modern landscape, signs and models provide a universe of illusion that overwhelms human subjectivity. The "critical institution" becomes a "simulacrum"—a copy without an original—because the critique being staged is no longer rooted in genuine opposition but is manufactured and absorbed entirely by the system itself.

In this state of simulation, the museum becomes a Baudrillardian "Hall of Mirrors." It ceases to be a site of genuine production and is reduced to a passive surface, reflecting only its own hollowed-out function in an endless, empty loop.

In this state, the museum functions as a "Hall of Mirrors." It ceases to be a site of cultural production and becomes a passive surface reflecting its own hollowed-out function. The institution is reduced to a space of "stockpiling and functional redistribution," a place where culture has lost its memory in the service of inventory management. The critical museum becomes merely an empty promise. This vacuum leaves the crucial question unanswered: If the institution is no longer being meaningfully critiqued, and its own critique is inert and purely performative, what is its actual, tangible function beyond the smooth maintenance of capital and cultural status?

Part II: The Un-Smooth Artifact: The Challenge of PLCFA

The void left by the exhaustion of Institutional Critique must be filled by a successor practice that inherently resists the "smooth" institutional apparatus. Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA) is that practice, and its very ontology forces the museum to confront its systemic inadequacies.

2.1 Defining the Tripartite Artifact

The PLCFA "One Original" is defined by its systemic, non-reductive nature, existing as a tripartite asset that cannot be disaggregated without destroying the work’s integrity:

The Physical Object: The material manifestation, subject to standard display and physical care.

The Conceptual Narrative: The core idea, instruction set, or philosophical framework that gives the physical object meaning. Drawing inspiration from conceptual art precedents where the idea or concept is prioritized over the technical execution , this narrative is not mere documentation but a material component of the work itself.

The Immutable Digital History: The cryptographically secured, decentralized record of the object’s provenance, ownership, and conceptual state changes. This record, often secured via blockchain, provides a unique digital certificate that verifies the artwork’s originality and eliminates concerns related to unauthorized reproductions.

The Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA) artifact is a tripartite, 'phygital' system. It inseparably weds a physical object, a conceptual narrative, and an immutable digital history, demanding an institutional framework that can manage all three components as one.

2.2 The Ontology of Resistance: PLCFA's "Un-Smoothness"

The acquisition of a PLCFA artifact fundamentally challenges the smooth institutional model. It is inherently "un-smooth" because its core components—digital and conceptual—are not simply supplemental ephemera or secondary notes; they are essential, demanding perpetual engagement. The object resists being acquired and archived as a static item.

This systemic nature imposes radical new demands on museum personnel. For the Curator, acquisition transforms from a one-time transaction into the acceptance of a "living system" that requires a long-term contractual commitment. Curatorial practice must evolve from object selection to systemic stewardship, requiring the initiation of "collaborations" and continuous dialogues focused on managing emergent issues and long-term outcomes for the work.

2.3 The Conservator’s Dilemma: Preserving the Non-Material

The acquisition of a PLCFA artifact fundamentally challenges the smooth institutional model. It is inherently "un-smooth" because its core components—digital and conceptual—are not simply supplemental ephemera or secondary notes; they are essential, demanding perpetual engagement. The object resists being acquired and archived as a static item.

This systemic nature imposes radical new demands on museum personnel. For the Curator, acquisition transforms from a one-time transaction into the acceptance of a "living system" that requires a long-term contractual commitment. Curatorial practice must evolve from object selection to systemic stewardship, requiring the initiation of "collaborations" and continuous dialogues focused on managing emergent issues and long-term outcomes for the work.

2.4 The Registrar’s Crisis: Accessioning a Distributed Asset

The registrar’s department, responsible for accessioning and collections management, encounters friction at the point of data migration and title definition. Modernizing Collections Management Systems (CMS) like TMS is already complex, requiring rigorous quality assurance and data auditing to handle complex or ambiguous material. The PLCFA asset introduces an added layer of unresolvable complication: the intersection of local material jurisdiction and global, decentralized digital jurisdiction.

While blockchain technology provides an unalterable record of ownership and provenance , this technological solution does not eliminate traditional fiduciary responsibility. The registrar must still perform intensive due diligence, as fraudulent or copyright-infringing digital assets are rife, even if the underlying token is unique.

The fundamental difficulty for collections management is a state of institutional jurisdictional schizophrenia. The physical object is anchored locally, subject to the laws and protocols of the host country. Conversely, the immutable digital history, being a distributed ledger, exists in a global system. Blockchains and digital assets face complex jurisdictional challenges regarding data privacy laws, requiring compliance with local regulations pertaining to server location, consumer citizenship, and potentially even the use of geofencing to avoid specific jurisdictions. The Registrar is therefore tasked with accessioning a single, indivisible artwork whose components are governed by potentially contradictory legal and operational regimes. Standard CMS protocols cannot resolve this conflict; only a preemptive, legally binding document can unify these disparate components under one framework of stewardship.

The immutable digital history of a PLCFA artifact creates "jurisdictional schizophrenia." While the physical object is anchored locally, its digital component exists on a global, decentralized network, creating complex legal and operational conflicts that standard protocols cannot resolve.

Part III: The Custodian’s Contract: A New Architecture of Stewardship

The only viable response to the ontological resistance of PLCFA and the resultant jurisdictional crisis is the formalized, binding legal framework: The Custodian’s Contract. This contract replaces the adversarial rhetoric of Institutional Critique with the concrete mechanism of systemic, collaborative commitment.

3.1 From Critique to Contract: The New Institutional Ethos

The Contract is posited as the logical successor to the performative self-critique that defined the museum’s recent past. It focuses on the specific, practical actions necessary for institutional viability in the future.

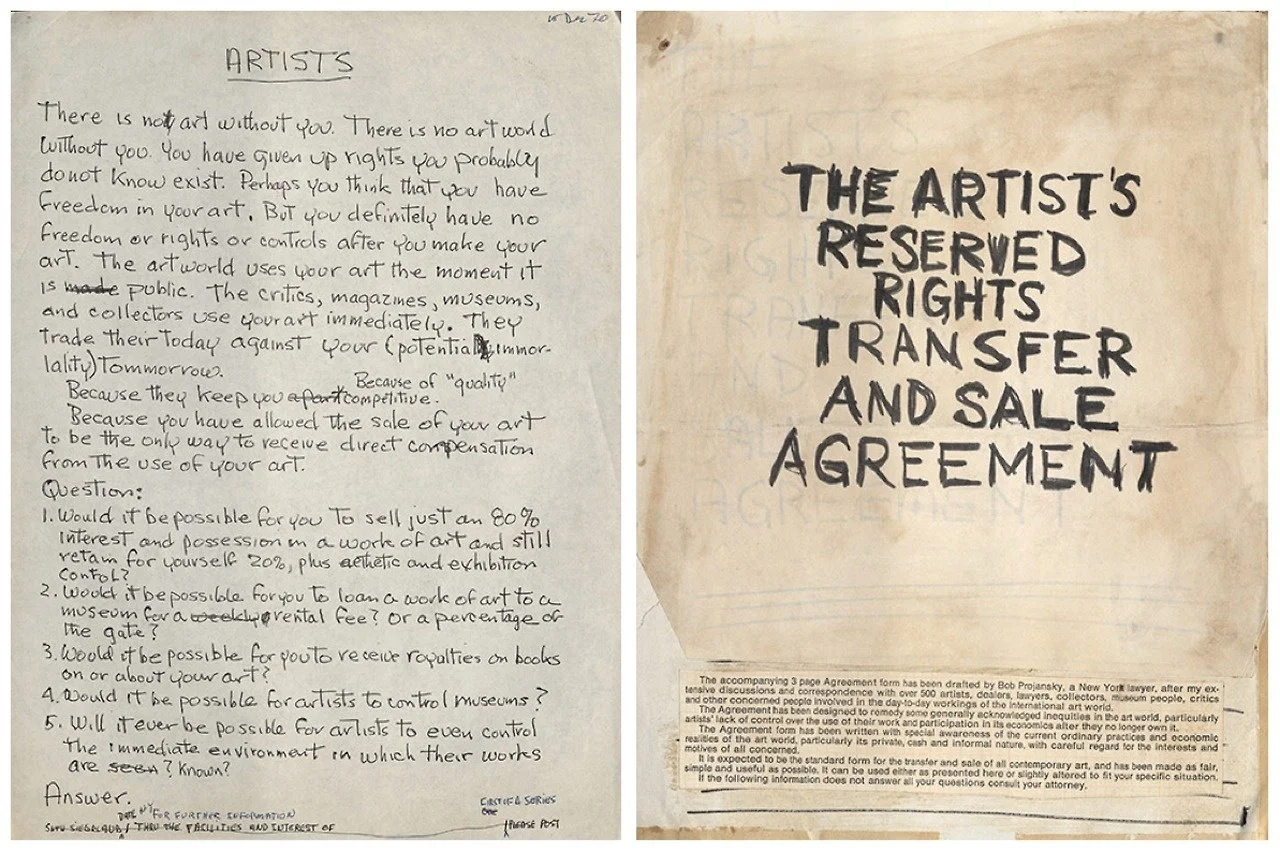

The foundation for this legal innovation lies in the Conceptual Art movement. In the 1970s, Seth Siegelaub and Robert Projansky conceived of the Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement (A.R.A.), a pioneering open-source contract designed to remedy inequities by shifting power toward the artist. The A.R.A. introduced practical stipulations, such as a resale royalty and the artist's right to veto exhibition. Siegelaub viewed this not as a "radical act" but as a "practical, real-life, hands-on, easy to use, no bullshit solution" to problems concerning artistic control after the work was sold.

The pioneering 1971 "Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement" by Seth Siegelaub and Robert Projansky. It was a "no bullshit solution" that shifted power to artists, establishing the legal precedent for using contracts to enforce systemic change—a foundation the Custodian's Contract builds upon.

The Custodian’s Contract leverages this precedent, expanding the legal mandate from simply protecting the artist’s financial and exhibition rights to enforcing the institution’s systemic stewardship obligation across all three components of the PLCFA artifact.

3.2 Defining the Custodial Obligation (The Terms of the Contract)

The Custodian’s Contract mandates specific operational transformations across every department, codifying the required shift from passive collection to active system maintenance.

Acquisition as Systemic Integration

The contract must fundamentally redefine what constitutes acquisition. The institution does not simply "buy the object;" it contractually agrees to integrate the entire PLCFA system into its operational infrastructure. This requires legal language that acknowledges the conceptual narrative and the digital history as equal, accessioned parts of the whole, binding the institution to their perpetual care.

Furthermore, the Contract establishes the artist as the "Hybrid Authority." Following the spirit of the A.R.A., the artist retains perpetual rights—not just royalties or exhibition vetoes—but the right to audit the digital history, verify the conceptual narrative's integrity, and, critically, ensure the exhibition protocols are being upheld. Since the use of blockchain technology to tokenize copyright often requires explicit contractual definition , the Custodian’s Contract must clearly delineate ownership, intellectual property rights, and responsibilities for future system updates and data migration.

Conservation as Perpetual System Guardianship

The Conservator's mandate is elevated from material scientist to system guardian. The Contract legally enforces the ethical imperative to preserve conceptual integrity. This involves a specific obligation to manage the narrative component, ensuring the longevity and philosophical adherence of the conceptual framework.

Most significantly, the Contract must mandate specific, measurable digital stewardship protocols. This means the institution is contractually obligated to perform scheduled data migrations to prevent technological obsolescence, ensuring the immutable digital history remains legible and accessible for centuries. The Contract must explicitly define policy regarding whether the digital storage is managed via proprietary systems or outsourced to external cloud providers, establishing clear lines of accountability for long-term preservation. New frameworks for "embodied stewardship," which arose from the conservation of performance and ephemeral art, provide the necessary ethical blueprint that the contract must legally enforce for PLCFA.

Exhibition as Systemic Legibility

The Curatorial and Registration departments are contractually obligated to shift exhibition practice from "showing the thing" to "making the entire system legible." An exhibition under the Custodian’s Contract must clearly and visibly present the physical object in direct, inseparable dialogue with its conceptual narrative and its verified digital history, including the unalterable blockchain record of its provenance. The exhibition itself becomes a transparent manifestation of the stewardship agreement, demonstrating the institution’s active commitment to the work’s complex reality.

3.3 The Mandated Perpetual Service Contract

The Custodian’s Contract transforms art acquisition from a one-time transfer of title into a mandated perpetual service contract. Traditional acquisition is concluded when the material object changes hands. PLCFA, however, demands continuous intervention: the conceptual narrative must be verified across generations, and the digital history requires constant maintenance and migration to remain permanent. The preservation of performance art already requires continuous care models. The Contract leverages the legal enforceability established by the A.R.A. to compel the museum to perform these long-term services indefinitely. By obligating the institution to continuous, resource-intensive maintenance, the Contract ensures that the museum’s function is active, undeniable, and impossible to simulate.

The conservation of performance art, such as Tino Sehgal's "constructed situations," already requires continuous care models. This provides the blueprint for the 'perpetual service contract,' legally compelling an institution to actively and indefinitely maintain the non-material components of a PLCFA.

Part IV: The Final Choice: The Museum as Mass, Not Mirror

4.1 Rejecting the Mirror

The passive museum, content to perform its self-critique and manage its collections with "smooth" efficiency, is structurally obsolete. The "Hall of Mirrors" reflects a hollow culture because it systematically filters out the friction necessary for cultural production. The institution must reject the comfort of lamentation over the decline of counter-hegemonic visual culture and focus instead on providing foundational structure for emergent, challenging practices.

4.2 Embracing the Foundational Mass (Sholette)

The evolutionary path forward is defined by the work of Gregory Sholette. Sholette introduced the concept of the "Missing Mass" or "Creative Dark Matter"—the vast, undervalued, and largely invisible artistic activity that structurally supports the narratives and political economy of the mainstream art world. The museum’s failure as a "Mirror" is its inability to anchor this mass.

The institution’s new function is to become the "Mass." This requires moving beyond reflecting the market or internalizing critique, and instead becoming the "foundational, structural anchor" that gives new, complex, and "un-smooth" art practices like PLCFA legitimacy and institutional permanence. This role demands an explicit commitment to complexity and friction, which the previously optimized, smooth system was designed to avoid.

The Custodian's Contract serves as the deliberate, legal imposition of structural conflict—the necessary "un-smoothness" required for this transition. The "smooth" institution eliminated external friction to optimize its brand. To anchor the highly "un-smooth" PLCFA, the institution must mandate internal friction. The Contract legally obligates departments—Registration dealing with international jurisdictional paradoxes , Conservation managing mandatory data migration, and Curatorial accepting Hybrid Authority vetoes—to engage in continuous, complex, and often conflicting collaboration. This mandated friction, now internalized and legalized, prevents the institution from retreating into passive simulation. It is the demonstrable evidence that the museum has moved from the performance of critique to the practice of enduring custodianship.

Practicing Custodianship

The "Custodian’s Contract" is the essential operational tool that facilitates the museum’s transformation from a passive archive to an active steward of phygital systems. It enforces a structural commitment to the complex reality of PLCFA, replacing the exhausted rhetoric of opposition with the precision of legal obligation.

The enduring thought for museum directors and institutional leaders is a choice regarding fundamental identity: Is the institution content to remain a passive mirror reflecting a hollow cultural landscape—continuing the exhausted performance of self-critique? Or will it accept the binding, complex commitment of the Custodian’s Contract, thereby becoming the essential, foundational "Mass" that provides permanence and value to the critical, authentic practices of the future? The former guarantees irrelevance; the latter guarantees the institution's necessary evolution.

The final choice: The institution can remain a passive 'Mirror' reflecting a hollow culture, or evolve into the 'Foundational Mass.' By providing the structural anchor for complex, 'un-smooth' practices, the museum actively secures its future relevance and becomes the site of authentic cultural production.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.